Tracing Roti’s Pasts, Presents, and Futures

THE PERFECT BITE

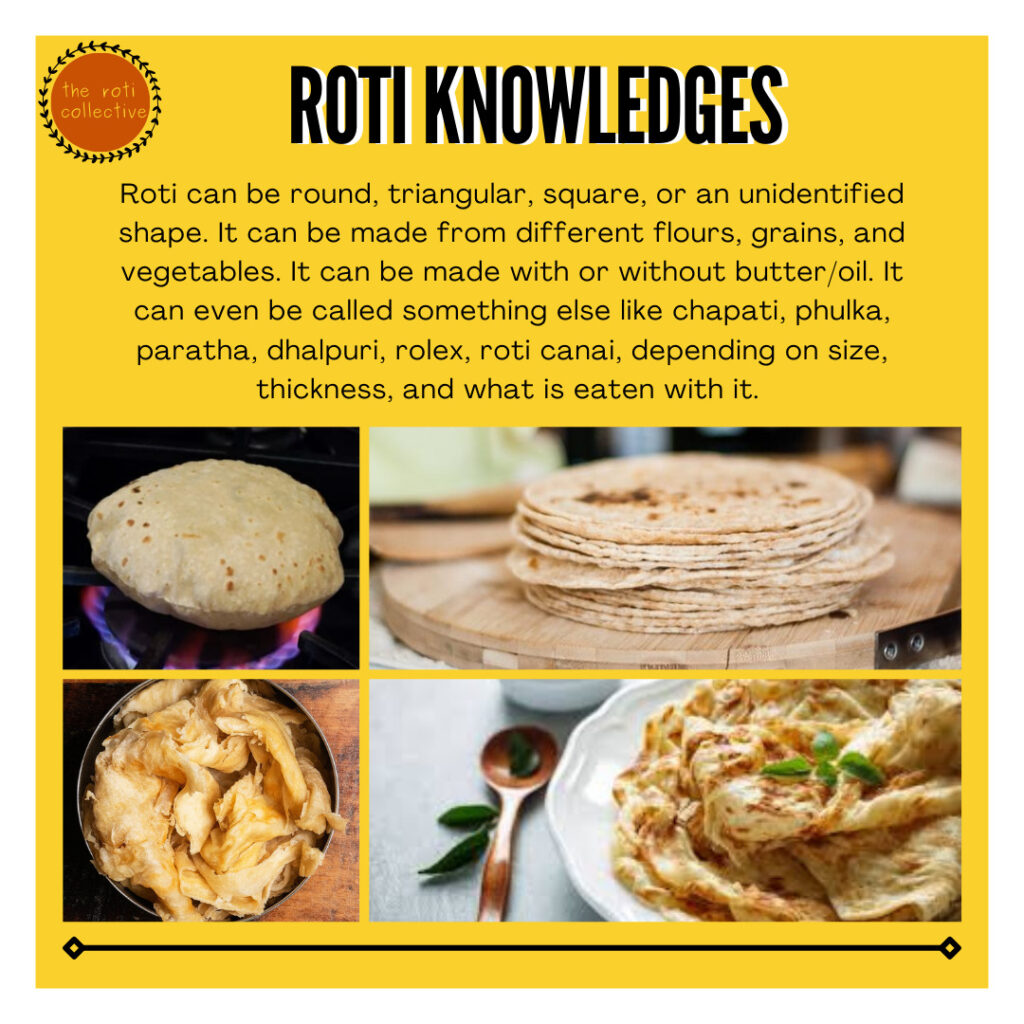

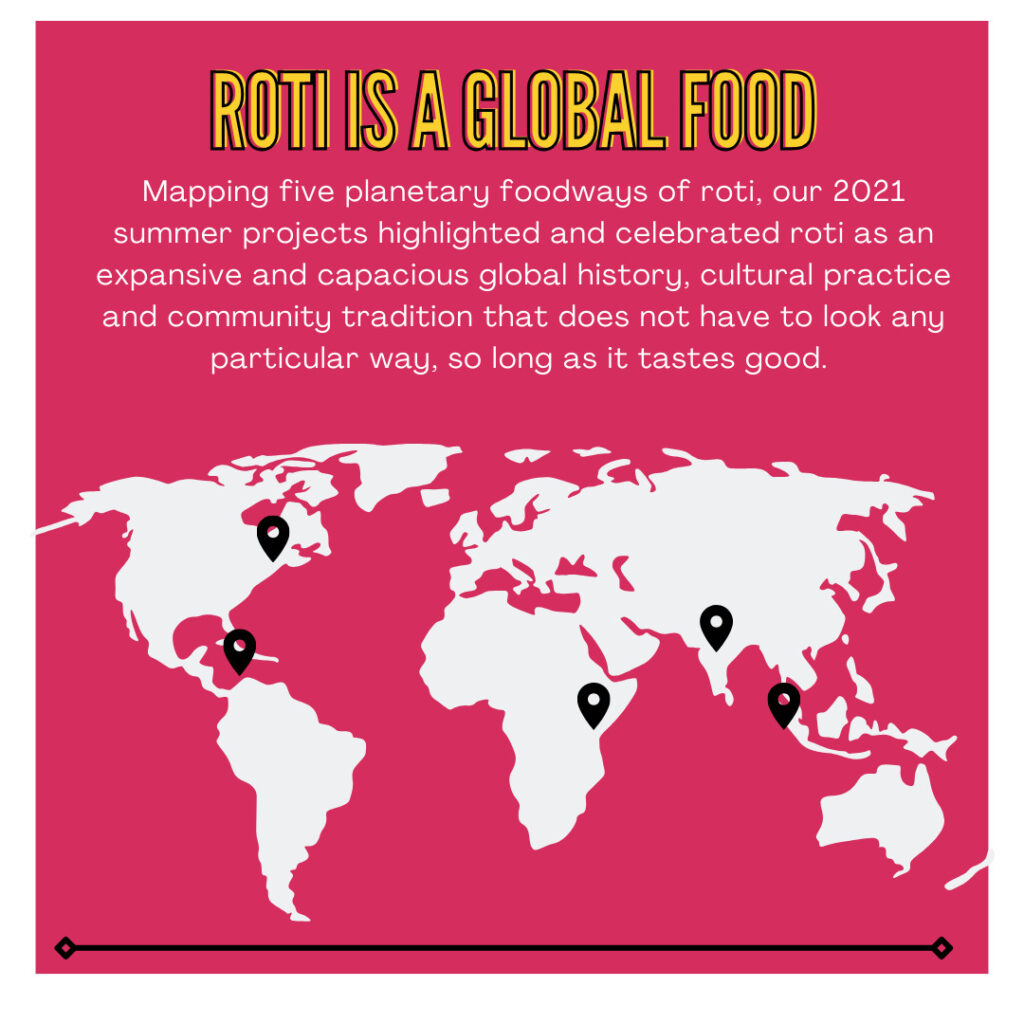

Roti, an unleavened flatbread, originated with ancient peoples of the Indus River Valley on the Indian subcontinent. Known by many names, including chapati and parotta, roti and the practice of roti-making has traveled the globe to become a culinary mainstay across many foodways in the “Global South.” Today roti and its many varieties connect cuisines and peoples across South and Southeast Asia, in East and South Africa, in the Caribbean, and their respective diasporas.

Making a basic roti requires only two ingredients—atta (refined wheat flour) and water—but the flavor and form can be improved upon with a little salt and some ghee (clarified butter). The flatbread’s springy pliability is one reason it’s so beloved. Somehow roti provides just enough structure for a scoop of a delicious daal or curry and just enough softness for the perfect, melt-in-your-mouth bite.

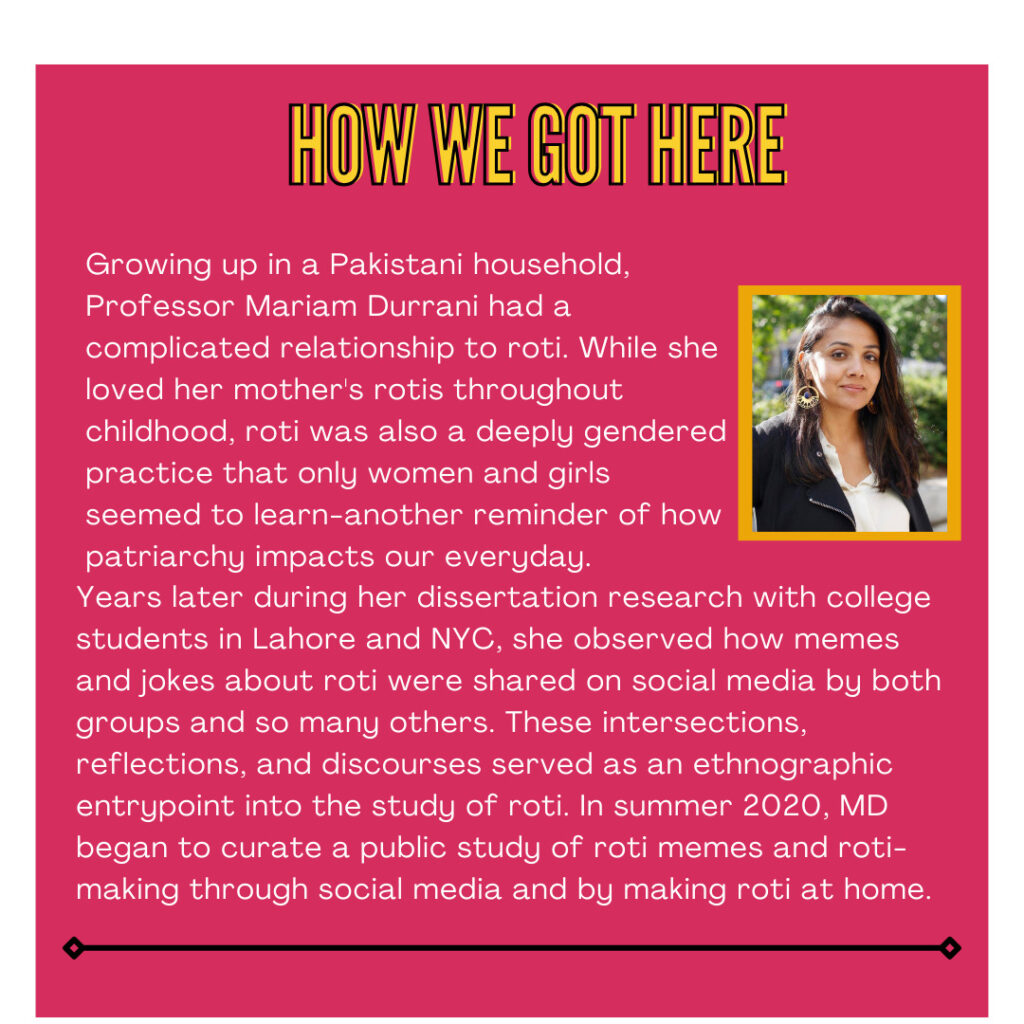

We both started our lifelong studies of roti at a young age—both as a frequent eater and observer of the food. I (Mariam) grew up in a Pakistani diaspora family, where I observed roti-making as an organizing tradition of my home culture, but one that remained a gender-exclusive space for girls, mothers, and aunties. During family trips to Pakistan, I noticed how it was common to buy roti from the neighborhood tandoors (or communal ovens) and restaurants where men made the roti. Some women made roti at home or employed cooks, both men and women. My curiosity about roti emerged through observations across these different contexts where roti was part of everyday life.

In contrast, my colleague and co-author Nilosree Biswas’ childhood memories do not include roti being made at her family home in Kolkata, where rice was the preferred daily starch. Later, as a documentary filmmaker, Nilosree met many girls, women, daily wagers, small holding farmers, and homemakers across India who made roti day in and day out. In many cases, making roti wasn’t a willful choice but an economic necessity—or part of unpaid domestic labor—within a highly gendered and classed society. In Calcutta on Your Plate, her book on Bengali cuisine and gastronomic history, she points out the absence of roti in Bengali meals until the mid-20th century.

Looking back, both my nostalgia for my mother’s handmade rotis and Nilosree’s filmic work on roti as a coercive labor regime reveal roti-making as a situated practice shaped by complex dynamics of colonialism, gender and class inequalities, and migration.

To better understand roti through both the personal and the political, I created the Roti Collective in 2021. The collaborative research endeavor is dedicated to the study (and celebration) of roti and roti-making in all its forms, alongside the histories that have shaped roti’s travels through space and time.

The Roti Collective’s events and projects are intentionally done in community, or in other words, collaboratively with students, artists, and writers—including co-author and filmmaker Nilosree and student researchers at American University in Washington, D.C., where I teach. Drawing on feminist research and scholarship, the Roti Collective is premised on a both/and approach—both appreciating roti forms, histories, and traditions, and learning about its complex role in everyday forms of social stratification.

The Roti Collective shared this introductory slideshow on Instagram in February 2022.

Mariam Durrani/@theroticollective

The Roti Collective shared this introductory slideshow on Instagram in February 2022.

Mariam Durrani/@theroticollective

The Roti Collective shared this introductory slideshow on Instagram in February 2022.

Mariam Durrani/@theroticollective

The Roti Collective shared this introductory slideshow on Instagram in February 2022.

Mariam Durrani/@theroticollective

The Roti Collective shared this introductory slideshow on Instagram in February 2022.

Mariam Durrani/@theroticollective

The Roti Collective shared this introductory slideshow on Instagram in February 2022.

Mariam Durrani/@theroticollective

ROTI’S PASTS

Roti, in its earliest versions, likely originated alongside the cultivation of ancient grains by peoples of the Indus Valley civilization sometime between 3300 B.C. and 1300 B.C. According to the Ayurveda, an indigenous South Asian medical system, mixing grains with water before pounding the blend into dough, rolling into flat discs, and then cooking over an open flame is believed to deepen the grains’ benefits. These steps incorporate the five elements of the universe—ether, air, fire, water, and earth—into a balanced staple food.

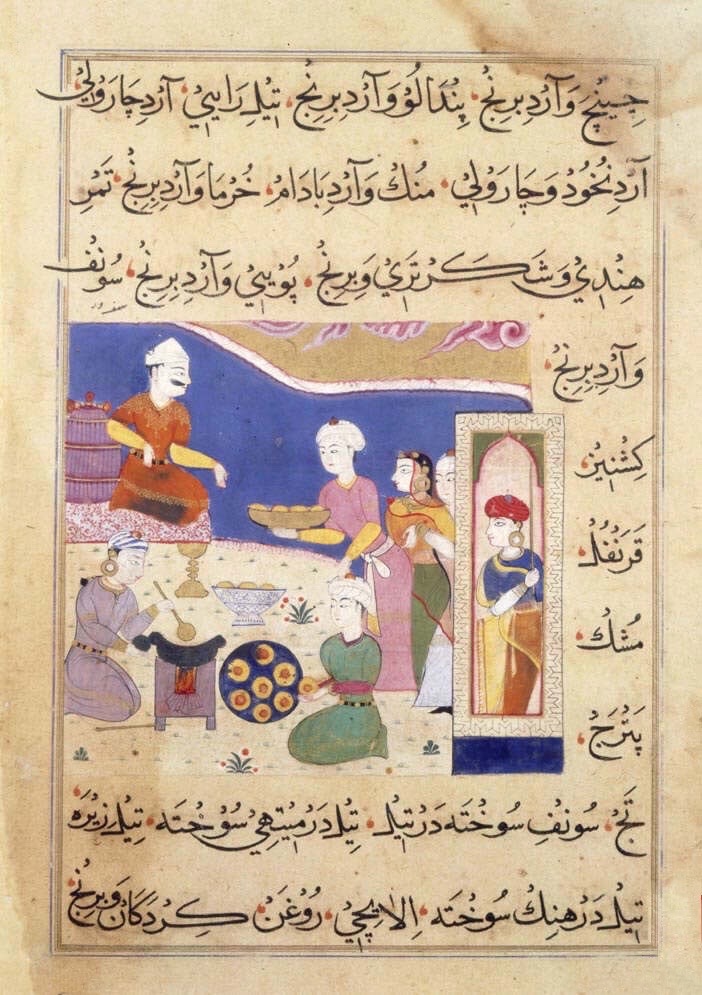

Similar flatbreads can be found across ancient and medieval worlds, including in Arab cooking texts from the 13th century. The first-known images of wheat-based savories appeared in a stunningly illustrated 15th-century cookbook called Ni‘matnama, or “Book of Delights,” written for the Malwa Sultanate on the Indian subcontinent. In a 16th-century Ain-i-Akbari report on Mughal Emperor Akbar’s government, an author refers to roti explicitly, explaining that the dish made with flour, milk, ghee, and salt “tastes very well, when served hot.” (Based on our extensive research and experience, this is still true.)

The ancestral food traditions of South Asia first traveled across Indian Oceanic trade routes beginning as early as the third century B.C. Later, from the 1830s to 1917, the British brought approximately 2 million indentured people from colonial India to British colonies elsewhere in Asia, the Americas, and Africa, often with no possibility to return.

Indentured people were forced to work as plantation and industrial laborers. Like enslaved Africans, whose labor was exploited by the British Empire, indentured laborers endured immense hardships and devastating losses. They also found ways to survive, create community, and make new homes, with new ways of cooking, eating, and caring.

ROTI’S PRESENTS

These legacies and adaptations are reflected in the many varieties of roti that exist today throughout the roti-eating diaspora—drawing widely from seasonal and locally available ingredients, traditions, and preferences.

Kale roti, for example, is a regional delicacy from Bangladesh that contains black gram beans (mashkalai) and other flours, and is eaten with mashed dishes made of chili, eggplant, tomato, or spiced beef. Using ingredients such as melted butter and cake flour changes the flatbread’s texture into the soft and spongy South African butter roti. In South Asia, Kenya, and Uganda, the flatbread goes by “chapati,” from the Urdu-Hindi root word “chapat” (slap), referring to the slapping technique used to flatten dough balls into thin, round discs before cooked on a tawa, or hot griddle. In Guyana, the name “clap roti” similarly points to a clapping technique for fashioning a flaky, tender roti—perfect for picking up steaming hot goat curry. In the Indian province of Gujarat, there is an extra-thin roti called a rotli. In Malaysia, the word “roti” can refer to many types of leavened and unleavened breads, including the famous roti canai, enjoyed as a circular, crunchy, flaky bread. And in various places, people have created versions to accommodate dietary restrictions and preferences, including vegan roti.

While reckoning with painful histories of colonial racism and its continued legacies across former British colonies, people incorporated roti into their local foodways and national traditions. In Trinidad, for example, over decades and after national independence, people across the country created popular specialties involving roti that have now become known in North America as “Caribbean” or “West Indian” roti. In the acclaimed documentary Dal Puri Diaspora, Richard Fung traces the long journey of Indo-Caribbean roti from “home fire to street stall to restaurant chain,” showing how the flatbread transformed as it moved from India to Trinidad to Toronto.

One variety of Trinidadian roti that exemplifies these cultural crossings is called by the playful name “buss up shut” after the dish’s resemblance in texture and appearance to a torn, or busted-up, shirt. In recent years, social media has provided an important space for many roti enthusiasts to share their culture and history through how-to videos for making buss up shut with dablas, or long, narrow wooden or metal spatulas that turn and break up the roti into soft folds while cooked on the tawa.

Like in Trinidad, roti’s travels to Uganda occurred prior to national independence, when the larger region was still under British colonial rule and its policies. In the late 1890s, the British Empire began construction on a massive 600-mile railway system as part of the imperial “scramble for Africa” to control the southern Nile River and connect Uganda to Kenya. The treacherous construction was done under deeply coercive labor conditions by both local African workers and indentured workers from India.

As members of newly formed multiracial, multiethnic communities, some Indian laborers became chapati sellers and shared the unleavened bread across East African foodways. Today we can thank those early chapati sellers for integrating and popularizing the flatbread into Ugandan street food cuisine. The cheekily named rolex, short for “rolled eggs,” consists of a vegetable-loaded omelet wrapped cozily inside a fresh chapati. Said to have originated by an experimental chapati seller in the 1990s, the rolex first became popular with university students in Kampala before spreading across the country and beyond.

Since 2016, the women-led Rolex Initiative has held an annual festival to celebrate the Ugandan Rolex and the street vendors who made it world famous. As Jonathan Okello, owner of The Rolex Guy, an upmarket Kampala restaurant, explains: “We’ve always had that saying: ‘Here you don’t wear rolex, you eat it.’”

ROTI’S FUTURES

Roti’s digital presence has been enlivened by memes and how-to videos shared on platforms such as YouTube, Instagram, X, and TikTok. One of the Roti Collective’s projects is to archive roti-related memes, illustrations, and online discourses by millennial and Gen Z social media creators and users, who often use the food to narrate their experiences and reflections on identity, gender, migration, and growing up.

Some creators offer content that playfully critiques roti’s gendered connotations while appreciating the expertise that roti-making requires. Their cultural commentary on social media often rejects patriarchal expectations about making the “perfect” round, flaky roti.

As one roti meme states, “No round roti, but still a hotty.” A tweet by @xprachix instructs, “I flip rotis with my hand, lower your voice when you talk to me”—a reference to roti-making as a craft that demands respect.

Across the communities and locales where roti is eaten, the finesse required to make the artful delicacy remains consistent, even as ingredients, recipes, and techniques change. As a New York Times article describes, roti is a “recipe mastered through repetition.” Roti-making in its diverse and delicious forms is due to the many peoples across generations who have done the work of making rotis and integrating them across global cuisines.

And what is roti’s future? Whatever it holds, we at the Roti Collective will continue studying both roti’s beauties and its complexities. We invite you to follow our project and join our study of what we call “roti-based knowledges.” To us, drawing on feminist scholarship, what that means is telling stories of roti and roti-making that center both nuanced histories of colonialism, indenture, migration, and displacement, and also legacies of survivance, craft, and creativity.