Why Aid Remains Out of Reach for Some Rohingya Refugees

Ameena (a pseudonym) is a 25-year-old Rohingya refugee in New Delhi, India, who is seven months pregnant with twins. Her face is gaunt. Often there isn’t enough food at home for her family of five. Nestled among other shanty houses, her home is made of bamboo with scrap boards as paneling; a tattered piece of cloth serves as the front door. Recently, the monsoon rains caused her to slip and fall. Now one of the babies in her womb is not moving. She knows she needs to see a doctor, but she cannot afford one.

When Ameena fled acts of genocide perpetrated by her own government of Myanmar in 2012, she and her husband came to New Delhi. They both suffer from debilitating deformities due to polio, and they heard that the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) office in New Delhi was helping Rohingya refugees. The UNHCR partners with the Indian government to provide free aid to help people obtain an education, a livelihood, and health care.

But as Ameena and others would learn, being offered access to aid isn’t always enough. Barriers to procuring those free resources often leave urban refugees to fend for themselves; many find they have to negotiate a system that inadvertently creates obstacles to reaching that aid.

Having spent 11 months with the Rohingya community in India from 2015 to 2017, I repeatedly saw how aid missed its intended target. As the UNHCR creates solutions to challenges that refugees face, these solutions can also serve as a catalyst for new obstacles or deepen already existing insecurities by creating additional barriers that are financial, linguistic, cultural, or exploitative. The UNHCR does a lot of good, but the organization could do a better job addressing challenges refugees face in accessing the services to which they are permitted.

In India, there are thousands of immigrants like Ameena from Myanmar. For decades, long before the August 2017 exodus that resulted in approximately 656,000 Rohingya fleeing to Bangladesh, the government of Myanmar has been torturing, kidnapping, raping, and burning down entire villages of the Rohingya people. The Rohingya are a Muslim ethnic minority from the state of Rakhine in western Myanmar. Their ethnic persecution can be traced as far back as Myanmar’s independence in 1948. This piece specifically highlights the plight of those who fled to New Delhi in 2012.

Images in magazines like National Geographic often show refugees in rural camps, living in tents at the borders of nations. In these camps, families are supplied with a place to sleep, have access to clean water, are given food rations, and are even provided with limited onsite medical services. For the most part, these are safe and secure communities, and their inhabitants often build cottage industries within the camp. But such spaces were only intended to be a temporary solution. In reality, some people live in these camps for decades, without permanent structures to call home or the freedom to explore other economic opportunities or mobility.

In some countries, such as Pakistan or Lebanon, refugee camps are not even an option for particular populations; in other situations, refugees choose to avoid them. As a result, 69 percent of today’s 22.5 million refugees worldwide are living outside of camps, primarily in urban areas. In India, urban refugees have access to UNHCR aid and protections once they are registered, but they are not provided with housing; they have to seek out their own places to live.

Even though being an urban refugee in India gives individuals some autonomy and agency to shape their lives, many like Ameena end up in slums, where they are vulnerable to exploitation. In part, this vulnerability comes from the fact that India does not want them to stay—the country provides no path to legal residency, making the legal status of Rohingya refugees indefinitely tenuous.

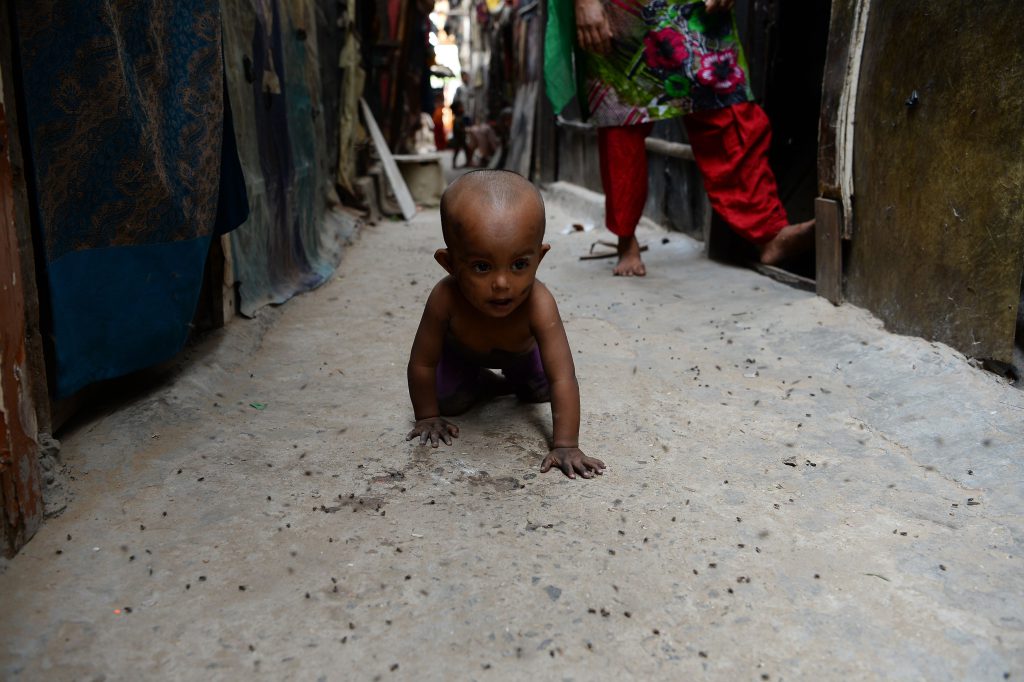

UNHCR officials have noted that “security conditions” for urban refugees can be uncertain, especially in Asia. According to a UNHCR 2017 report on alternatives to camps, conditions are considered unsafe for about 50 percent of urban refugees in Asia. Landlords have been known to charge high rent for squalid conditions; law enforcement will often solicit bribes by threatening detention; children have been conscripted into underage labor and scavenging; some girls and women turn to prostitution; and men work day labor jobs for little pay. As undocumented migrants, urban refugees have no legal recourse to protect themselves. Fear of detention or deportation further exacerbates their feelings of insecurity.

Ameena’s home is located on the outskirts of New Delhi. In 2015, when I first met Ameena, I found her living, along with 45 other Rohingya families, in tight quarters about the size of two basketball courts. In the dusty, desolate, and quiet settlement, there is no running water or bathrooms, and only intermittent electricity. Refuse is collected alongside the settlement in an unsanitary mound where children often play. On a clear day, just past the crematorium, you can see the tall skyscrapers of the nearby city of Noida.

Ameena knows she can legally visit a health clinic, but getting to one is a challenge. She feels that the cost of a rickshaw ride, about 50 rupees (US$.74), is more than she should be spending, given the needs of her family. Her husband works as a day laborer earning only 200 rupees a day. “A sonogram costs 1,000 rupees. It’s very difficult for us. We are not in a good position like other families,” she tells me. The city bus, at 10 rupees, is more affordable, but in her expectant condition, the jostling makes her feel ill.

Some refugees, including Ameena, can communicate fairly well in Hindi, but they aren’t necessarily comfortable with it; some women told me (in Hindi) that they don’t speak “good Hindi.” Recognizing this shyness or perceived inability, UNHCR partners in Delhi selected one man from the Rohingya community to serve as a liaison, tasked with providing transportation and translation.

His appointment, however, created a situation of exploitation. In hushed tones, Ameena tells me that it costs 500 rupees to go to the free clinic with this man. I confirm with Ameena that he is paid by the UNHCR for his translation services and transport. She says, “Yes, it’s free, but he charges.” It was then I understood that the broker from the community was leveraging his ability and opportunity to create financial stability for his own family. The UNHCR had inadvertently created hierarchies of power within the community.

Not all Rohingya women feel comfortable talking to a man about their bodies, especially in a culture where a woman’s honor is of utmost importance. Providing a translator is a difficult task for the UNHCR because often there are few women from the refugee community who can speak Hindi fluently enough to talk about medical matters. And ambitious women who dare to become translators are criticized by the elders as being too free or “immoral” by engaging in work outside the home.

Eventually, with financial assistance from a nongovernmental organization, Ameena went to a doctor, only to have her fears confirmed: One of her babies had died of umbilical strangulation.

Of the four health care workers I interviewed in New Delhi, each emphasized that women need to come in for regularly scheduled prenatal checkups. In frustration, they would say things like: Why don’t they come? It’s free! Or they would explain: The women are uncultured. They are uneducated.

But refugee women understand the importance of prenatal care. They want the medical assistance. They, like women around the world, want the best for their children. But the situation is complicated. Ameena overcame financial hardships, linguistic challenges, cultural barriers, and exploitation to finally see a doctor. But for her baby, it was too late.

Ameena shows me a file full of reports from her doctor. It is riddled with procedural language written in English. Crouched on the dirt floor in her hut, she looks at me for an explanation. In a small blank space, the doctor had drawn a fetus with an umbilical cord around its neck. I have nothing more to offer than to point to the picture.

I ask about the other baby. She looks at the floor and says she has to carry both the dead fetus and the live one to term. The doctor wants her to deliver at the hospital and not, as is the common practice, at home. She sighs and says she will “bear the burden” somehow.

Over several decades, the UNHCR has become very good at negotiating the concerns of access to education, health care, and livelihoods. However, addressing the needs of refugees requires spending extended time in their living space. Underfunded and perhaps short-staffed, the UNHCR’s assessment of communities is usually left to implementing partners. These partners are local agencies contracted by the UNHCR to help advance their mission of human security. But the partners’ employees are often underemployed and come from different cultural perspectives than the communities they serve. Implementing partners are often seen as irrelevant by refugees like Ameena, who prefer to deal with the UNHCR directly, in the hope that such contact will spur things to change.

The UNHCR should partner with social scientists who take the time to get to know individual refugees and their families—and who are trained to peel back complex layers to gain a deeper understanding of the cultural, structural, and economic constraints on people’s lives. Policies like the one that funded the translator in Ameena’s community end up pitting refugees against one other, perversely creating further opportunities for exploitation and abuse.

In a world where global mass migration is becoming an endemic issue, collaboration is of utmost importance. The work of social scientists can and should help to inform urban refugee policies. It takes time to unpack the complexities of refugees’ situations and to understand that providing aid is not always enough to keep people healthy and safe.