#MeToo Anthropology and the Case Against Harvard

On February 4, The Harvard Crimson broke the news of an open letter, signed by 38 faculty members, in support of John Comaroff. This prominent professor of anthropology and African studies had been placed on unpaid administrative leave two weeks earlier following a university investigation that had found him responsible for violating sexual harassment and other professional conduct policies. Another open letter had been published the day before in The Chronicle of Higher Education, with 55 more names of higher education faculty and others from around the world supporting Comaroff’s assertion that the accusations were all just a result of a single, misunderstood incident.

Neither letter addressed the nature or severity of the accusations against Comaroff. They instead focused on his character as a “devoted scholar” and “excellent adviser,” or on the due process politics of Harvard’s Title IX proceedings.

A few days later, three graduate students—Margaret Czerwienski, Lilia Kilburn, and Amulya Mandava—filed a lawsuit against Harvard in Boston federal court. The 65-page complaint—widely circulated on social media—details the profoundly serious nature of the allegations against Comaroff involving physical and emotional violence experienced by several students over multiple years as well as Harvard’s inadequate response. Afterward, the majority of the Harvard letter signatories and some of the influential names on the Chronicle letter rushed to retract their signatures.

However, the damage was done. The networks of power and prestige had already closed ranks around one of their own and made it clear to everyone in their academic circles that Comaroff’s reputation was more valuable than the lives and careers he had allegedly harmed. Other statements, this time denouncing the original Comaroff supporters, followed—including a letter signed by 73 Harvard faculty and then another open letter from anthropologists circulated online that had gathered over 800 signatures as of the end of February.

The news coverage and outrage about Comaroff will eventually die down and disappear. It always does. Many of us involved in the fight for justice fear, however, that the academic system, and those at the top of it, will not enact substantial changes as a result of this case. Rather, we believe that those in positions of power will once again nod and consider the matter closed and the “bad apple” adequately punished.

As someone who has worked directly with survivors of sexual violence as part of the MeTooAnthro Collective, I want to underline that incidents of sexual harassment and assault are not isolated actions. Rather, such abuses are endemic in the structures of academia.

The very cycles of investigation, reporting, and legal action that are meant to address these harms often fail to acknowledge that injustice has been, and continues to be, perpetrated not only by individuals but by the people and organizations around them. The problem is not just the pervasiveness of sexual misconduct in the academy and the lack of adequate institutional responses to reports of it, but the comfortable fiction that abuse is limited to isolated interactions and is mostly meaningless unless it rises to the level of a crime.

So, what is it about academia—and anthropology specifically—that allows this kind of systemic abuse to thrive?

As feminist scholars in anthropology and related fields have often pointed out, sexual harassment and assault do not exist alone.

These abuses of power get perpetrated alongside a range of other harms, including silencing, intimidation, bullying, professional retaliation, veiled threats, loss of opportunities, and exclusion from citations. Frustratingly, cases like the one at Harvard often continue despite graduate students and some faculty repeatedly calling for anthropology to turn its critiques of power and merit back on itself so as to disrupt the very structures that allow these problems to recur over and over again.

As new cases of harassment, retaliation, and discrimination inevitably emerge, there will undoubtedly be shock across news outlets and social media, but it won’t be any surprise to those of us actually in these halls.

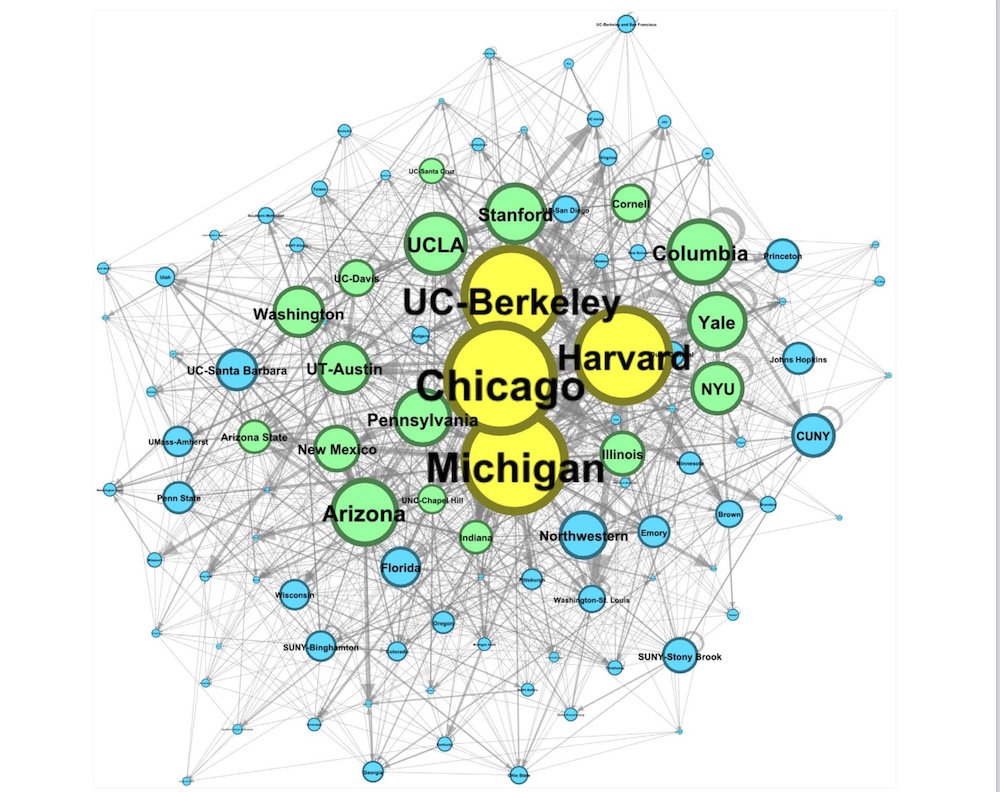

As the discussions continue, let us not forget that academic systems and institutions have a variety of ways, not often acknowledged in conversations about sexual harassment, of preserving and reproducing themselves. Limited hiring practices that favor graduates from prestigious programs are one such example. In fact, one could easily contextualize the current Harvard scandal in relation to U.S. anthropology’s staggeringly nepotistic hiring practices. As researchers have shown, more new tenure-track anthropology faculty hires are drawn from the University of Chicago (where Comaroff used to teach) and Harvard than any other programs.

Across academia, alumni from around 15 elite American graduate programs populate the majority of faculty ranks in a variety of disciplines across the U.S.—thus creating the very insular networks that protect abuse and reduce the diversity of ideas. This situation helps explain how the open letters were able to muster such a quick response from scholars in anthropology and related fields, mobilizing protective networks more concerned with perceived attacks on Comaroff’s status and renown than on the safety and dignity of the named students coming forward to reveal their experiences.

Those of us both in and outside of academia must demand real accountability from institutions. Since the 1970s, one of the major ways public and private universities, and even corporations, have responded to allegations of sexual harassment is through performing mandatory trainings, as though a seminar on gender inequality or workplace decorum will immediately fix the problem for all but the worst offenders. This implies, of course, that those who abuse and those who fail to stop it do so out of ignorance and not, as I and many others contend, out of calculated intent and a secure knowledge that their positions will protect them.

Researchers have shown, however, that workplace trainings simply aren’t effective at reducing sexual harassment. What’s needed is structural change that addresses the root causes of inequality and discrimination.

Many people rightly ask why this is such a problem for anthropology. How could a discipline that prides itself on studying the nuances of power and culture so completely fail to address its abuses in their own departments? Shouldn’t social scientists be better at dealing with these kinds of issues?

Sociocultural anthropologists have long been fixated on disparities of power when it comes to the relationship between ethnographers and their “ethnographic subjects” during fieldwork. Most anthropologists today also claim progressive political commitments, such as improving visibility for Black, Brown, and Indigenous researchers or opposing anti-trans legislation. But while conversations about power have led to more diverse course syllabi, more gender-aware perspectives in and out of the classroom, and more refined social justice stances off campus, they have yet to fruitfully challenge academic anthropology at its core.

The Comaroff case highlights these contradictions. Today U.S. anthropology as a field is both closely attentive to power inequalities and beholden to dominant systems and ideologies of the Western academy that preserve the illusions of meritocracy and objectivity at all costs. The wrongheaded belief that those who hold power within faculty ranks do so because of their benevolence, superior abilities, and freedom from bias actually creates the circumstances for abuse, rather than reducing the potential for harm to those who are vulnerable.

Those of us in academia only need to look at the numerous incidents of professional and sexual misconduct at conferences, public institutions, and journals in recent years to see that anthropologists aren’t any savvier than anyone else when dealing with abuses of power or pervasive gender and racial inequalities.

In response to this recurring problem, the MeTooAnthro Collective was founded in 2015 by a group of international graduate students and early career researchers as a grassroots initiative to begin changing the discipline from within. Our resources were limited, but within a short time, we were presenting workshops at conferences and publishing open access materials for interdepartmental trainings and an action plan that offers strategies for responding to harassment at events.

While our ongoing work is valuable, it’s not enough to solve the deeper systemic problems that allow abuses of power to continue. We have said, for years, that individual responses to systemic injustice will not right the wrongs of the past or prevent further wrongs in the present.

That’s why, for many of us, the case against Harvard isn’t unique. It’s just one more reminder that entrenched systems of power are doing what they have always done and will continue to do.

That won’t change until the discipline as a whole faces the heaviest critique we’ve leveled at it: Anthropology, despite its dedication to analyzing cultural change, has yet to fully make plain that knowledge is often not produced despite systems of oppression, erasure, and harassment—but because of them.