Japan’s Wartime Past Looms Large Over Militarization Efforts

The thunderous pounding of a military helicopter from the nearby Ground Self-Defense Force (GSDF) training range echoes across the sleepy coastal neighborhood of Katsuhira. The noise acts as a steady accompaniment to the random trill of the cicadas in this corner of the Araya area of Akita City, Japan. I walk the streets, seeking residents’ opinions of their government’s plan to convert the range into a missile base.

On that day, August 15, 2018, it was a fitting time to be thinking of war and loss. It was the peak of the annual Buddhist bon festival holiday time, when the souls of ancestors are said to revisit the land of the living. It was also the 73rd anniversary of Japan’s WWII surrender announcement, presented to the public in 1945 as a prerecorded radio message read by Emperor Hirohito, who was worshipped at the time as a living god. At the annual war-end commemoration ceremony 280 miles to the south in Tokyo, Hirohito’s son Akihito expressed “deep remorse” for Japan’s wartime aggression in his final address as emperor. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe also spoke. However, he eschewed apologies and sent a ritual donation to the Imperial Shrine of Yasukuni—a focal point for nationalistic sentiment. The shrine consecrates the souls of nearly 2.5 million war dead from conflicts since 1853, controversially including those of WWII war criminals.

As an anthropologist who studies regional issues in Japan, I have observed the emergence of a resistance movement against local militarization in the Araya area of Akita City and especially in the neighborhood of Katsuhira. Residents’ concerns about the potential missile installation recall when populated areas and military and industrial zones became targets—and when the government strongly encouraged citizens to sacrifice their own individual lives for the good of the many. Such memories cannot be drowned out by declarations of a national need for boosting self-defense capabilities in the face of contemporary threats.

The trouble began for this peaceful Akita neighborhood in November 2017, when U.S. President Donald Trump declared in a press conference that Japan would soon acquire a large amount of American military equipment. The purpose was twofold: to help reduce trade imbalances and to better enable Japan to knock down any North Korean missiles that should cross its territory, as two had done earlier that year.

Aside from anti–arms trade and pro-peace groups, few people in Japan were deeply vexed by the announcement that the country would continue its U.S. military-hardware spending. For most, it seemed a necessary evil. But a month after the initial revelation, many of Akita City’s 300,000 residents were shocked to learn of the Defense Ministry’s plan to put one of two Lockheed Martin Aegis missile systems in the GSDF’s Araya training ground, next door to the neighborhood of Katsuhira. This tranquil, relatively isolated city has never hosted any missile batteries other than mobile PAC-3 interceptor units, which were temporarily deployed in the Araya training ground a number of times in anticipation of North Korean missile launches.

“Why in Akita City?” many asked.

The answer was that the GSDF area belongs to the government, which has deemed that the northern location is an ideal place for one of the missile bases. (The government plans to install the second in a less densely populated coastal spot 620 miles to the southwest, where local aversion is also high.) This information, however, did nothing to snuff out the embers of resistance that had begun to glow in Katsuhira and across the rest of Akita City’s Araya area. Some 16 Araya neighborhood associations, representing about 13,000 residents, have taken official anti-base stances, and opposition seems to harden each time the Defense Ministry holds a briefing.

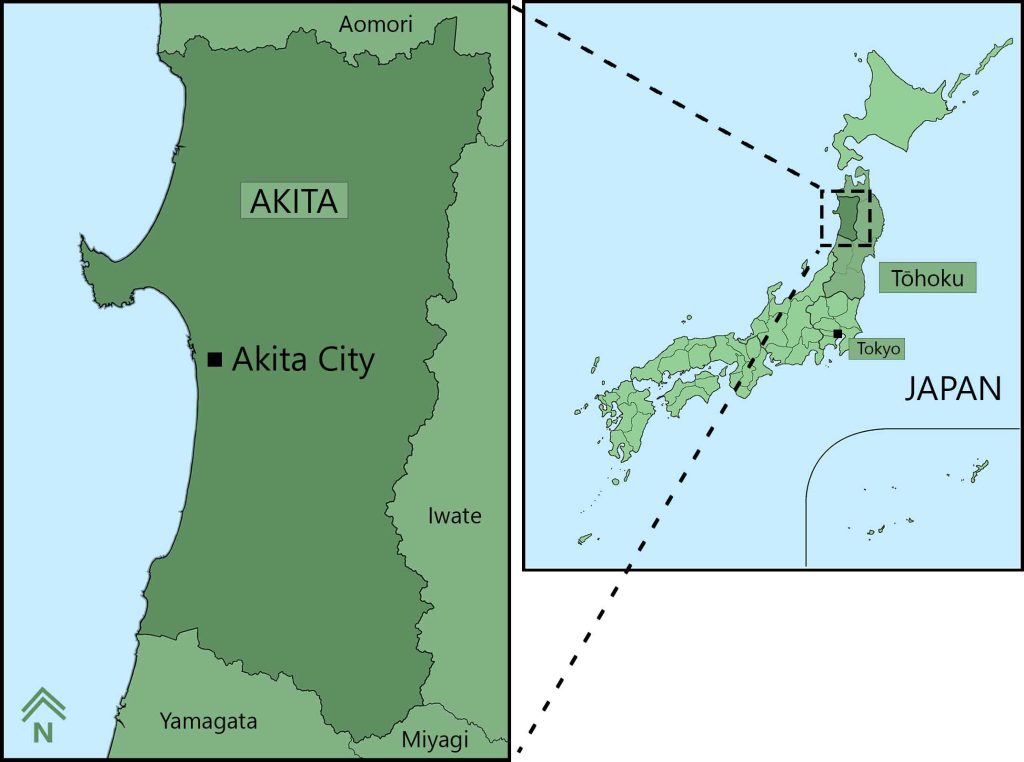

Akita City is the capital of Akita Prefecture, one of six administrative territories that make up the region of Tōhoku, the northeastern third of the main island of Japan. (The devastating March 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami occurred in this area.) Slightly bigger than West Virginia, Tōhoku has a population of about 9 million. Just to the south, the smaller Kantō area, home to Tokyo, holds 43 million people. Due to its massive population, and the fact that it hosts the central government, Tokyo tends to get its way with Japan’s regions, including Tōhoku and Okinawa. In order to maintain nearly unbroken control of the country since its CIA-supported launch in 1955, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party has coaxed votes from certain demographic groups through financial incentives. In addition, to satisfy Tokyo’s thirst for electricity, the government has seduced municipalities with massive, and addictive, cash payouts for hosting nuclear power stations or related facilities, such as the Fukushima Daiichi plant in southern Tōhoku that was ravaged by the 2011 tsunami.

But these aspects of Tokyo’s heavy-handedness have entailed a degree of choice—residents have at least been able to vote on whether or not to take nuke money, for example. This was not the case for Okinawans, who have been forced to live in a perpetual state of foreign military occupation as the reluctant host to 70 percent of Japan’s U.S. military facilities. Okinawan residents have protested both the existence and the expansion of foreign military bases over the last several decades. Now, many in Akita City bristle at the prospect of having to live next to a missile base that could very well become a target in the event of war.

“Now I know,” said one resident in a local TV news interview, “how the Okinawans feel.”

On that sweltering August day, it proved easy to find Katsuhira residents opposed to the missile base plan. “I’m absolutely against it,” declares one older woman, whose family runs a carpentry company. [1] [1] Names have been withheld to protect the sources, as is customary practice in anthropological fieldwork. She is kneeling on the floor of the entryway of her large wooden house, a mere 300 yards from the GSDF training ground. “I’m 80 now,” she explains, “and I’ve been living here in this spot for 50 years. I have a grandchild in college who is studying to be a high school teacher and who wants to come back and live here and work in the future. How can I expect this to happen if they build that thing right over there?”

This concerned grandmother is one of many who remain unswayed by the anti–North Korea rhetoric pervading the media or by government fearmongering. Some of her neighbors, however, have been persuaded. But they resolve the contradiction between the apparent national need and local worries through “NIMBYism”: maybe it’s necessary, but “Not In My Back Yard.”

As one example, a man out for a jog says to me, “I guess such a base is needed, considering North Korea, but not in this densely populated place. … It could become a target.” A similar sentiment is echoed by a man bundling hydrangea branches outside his house, which stands about 500 yards from the training area, near the middle school: “In this era, it’s probably necessary … but right here? Hmm …”

I find NIMBYism of an especially cynical sort in the words of a stocky, well-weathered man who seems glad to take a break from hoeing his parched vegetable garden to complain about the lack of rain. “North Korea is scary and unpredictable,” he mutters in a thick local accent, “so it’s OK … as long as there’s no effects on the locals. If there’s some effect, then it’s no good.” Potential effects include electromagnetic waves emitted from radar systems and the possibly of being targeted in the event of open hostilities. “But there’s no use in fighting the government,” he sighs. “It’ll do what it wants to do.”

“No,” asserts the 80-year-old woman. “I disagree. We have to stand up and fight while we can. If we don’t, what can we say later?” In Japan, worries about what might happen in the event of war are grounded in experience—hundreds of thousands of civilians were killed in 1945 alone, either because they were too close to military or industrial targets, or because they were the targets.

One 88-year-old Araya resident remembers war-time life in Tokyo. “I lived in Tokyo during the war,” she tells me. Her current home lies about one mile from the GSDF area. “Squadrons of B-29s would fly over every day on their way to bomb the airfields, and then back again. Something like a missile base will always be targeted if war breaks out.”

In one of its briefings, the Defense Ministry announced that it did not expect the planned missile base to ever become a target. “Why is a base needed then?” scoffed concerned residents. Statements like this are sure to remind citizens of how the government used wartime promises of victory to justify the confiscation of private property and conscription—most insidiously for the infamous tokkō-tai (kamikaze) special attack squadrons.

Furthermore, worries about being targeted are grounded in the local collective memory. Although Akita City was spared the very worst horrors of WWII, it did experience the shock and pain of being targeted. Over several hours, beginning on the night of August 14, 1945, American planes bombed Akita’s port area and the nearby oil refining facilities, killing several hundred people. “I’m old enough to remember the war, and I remember when Akita’s port was attacked,” says the 80-year-old grandmother. “I can’t forgive these adults who are making war plans now with no regard for the children of the country.”

“Adults?” I ask, to which she replies, “The politicians—they should be ashamed of themselves.” Similarly, the 88-year-old woman who experienced war-time Tokyo says, “It’s the job of the politicians to use diplomacy to avoid war, not to prepare for war … like in the old days. It’s terrible what [Prime Minister] Abe is doing.”

Feelings about sacrifice and war are mixed in Japan, with some divisions roughly aligning with religion. While Shintoism can be used to foster self-sacrifice, Buddhist-inspired philosophies emphasize the well-being of the individual. Although state Shintoism was largely dismantled after Japan’s 1945 surrender, currents of it still flow through certain shrines—the central representations of this ancient religion—most notably, the Imperial Shrine of Yasukuni in Tokyo. By way of the national Association of Shinto Shrines, these shrines exert a degree of influence over the government, largely through ties with Liberal Democratic Party politicians. These shrines remain focal points for nationalist sentiments that can be used to argue for sacrificing the few for the many.

By way of example, a sign in a display case on the grounds of Akita’s Sōsha Shrine reads: “We are flower blossoms, doomed to fall … destined to bloom again in the divine garden [of Yasukuni Shrine].” It is a variation of a wartime song used to encourage kamikaze pilots. The signboard minces no words in glorifying the final acts of several dozen who hailed from Akita. A black granite slab standing nearby declares that the Pacific War was necessary to free the Asia/Pacific region from Euro-American colonialism.

In contrast, Buddhist temples generally eschew jingoism and direct involvement in state politics in favor of nurturing individual health and wellness. Half a mile south of the GSDF training range stands Shōheiji, a large temple whose grounds offer a scenic view of the Araya area. Clustered on a hill, aging stones memorialize soldiers who died in the war. The strongest hint of nationalism here is a tendency for the Chinese character for “hero” to appear in the dedications on the backs of these cenotaphs. This imported religious approach, in focusing on appeasing the souls of both the dead and the living, better expresses the way that most Japanese people feel about the very real—and high—human costs of warfare.

The Akita governor and the city mayor have taken cautious anti-base positions, but the people of Araya may come to feel like the stout, resigned farmer who sees futility in fighting; the Ministry of Defense is a tough adversary, especially in the chauvinistic, neoliberal Abe era.

Some recognize this: “All the people of Akita City should fight against it, because it’s not only a Katsuhira or Araya issue,” says the man who lives near the middle school as he ties up a bundle of hydrangea sticks. The 80-year-old grandmother agrees and is joining with many others who hold a more Buddhist-oriented view of state militarization—a development of which the prime minister should take note.

Still kneeling in her entryway, looking pensive, the grandmother reflects on her attachment to her home of 50 years and her motivation to resist: “I walk over to Shōheiji Temple pretty often, and in the cemetery there is the grave of a soldier who died in the war at the age of 19. Engraved on the stone is a message from his mother—an apology for not being able to protect him from being sacrificed. There are many such graves in that cemetery, and in others. I don’t want that to happen anymore.”