Ebola Prevention Caught in the Bushmeat Trap

In 2015, as an Ebola epidemic raged in West African countries, messages began popping up on Cameroon’s social media sites and on posters distributed by UNICEF warning people to stay away from “bushmeat”—or wild game meat. Many locals reacted with disbelief. As one man told us, “Sometimes I wonder where this is coming from, especially as we grew up eating bushmeat as a regular meal and nothing happened.” For him, and many others, the idea that hunting and eating bushmeat might spread disease was nothing more than a myth, or perhaps part of a larger anti-bushmeat conspiracy.

From 2014 to 2016, West Africa experienced the most deadly Ebola outbreak in history. More than 11,000 people died, primarily in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, as the horrific and often fatal virus spread from animals to people, and then from person to person. Cameroon remained outside the affected zone; no one in Cameroon contracted the disease. But this hasn’t left the country untouched by the epidemic.

Cameroon was well within the boundaries of a rising tide of trepidation about Ebola at all levels of society, claiming people’s sense of security and everyday social stability as its victims. During the early days of the spread of another frightening disease, AIDS, during the 1980s, the intense fear of infection came to be called the “second epidemic.” This term also applies to the psychological and social impacts of Ebola.

Beginning in March 2015, as medical anthropologists working on the study of social factors in the spread of infectious diseases, we conducted interviews with 92 people in several locations around Cameroon. We asked about their attitudes and beliefs regarding Ebola, as well as their efforts to prevent infection. Our work throws a spotlight on how a public health campaign may have backfired in that it came to be seen as anti-bushmeat. Well-intentioned efforts to curb the spread of disease can have counterintuitive and destructive results, such as a loss of trust in public health messages. This can lead to a highly risky situation in a time of accelerating emergent infectious diseases throughout the world.

Cameroon is sometimes called “Africa in miniature” because of its many ecological zones. Only a bit larger than Sweden, the country boasts over 8,000 plant species and a wide range of iconic African animals that includes gorillas, black rhinos, elephants, and cheetahs.

In southern Cameroon, the middle of a rainforest zone has been opened up to local hunters over the last several decades as a result of the construction of logging roads deep into pristine areas. These forests support abundant wildlife, including chimpanzee and gorilla populations, as well as various kinds of monkeys, bats, pangolins, rodents, and deer.

Bushmeat has both practical and cultural importance in Cameroon and elsewhere on the continent. Consumption of game meat has been shown to help prevent childhood anemia, or iron deficiency, a significant risk in low-income countries. Traditional dishes such as peppe, or pepper soup, are made with small pieces of game meat along with plantains and onions, or other vegetables, as well as toasted spices. The consumption of this prized fare is a rich part of local social tradition in Cameroon and in West Africa generally. Game meat is vital here in a region that sees deep ties between wildlife and many traditional African values and practices, as well as food security and general well-being.

Technically, the practice of hunting, selling, and eating wild game is illegal in Cameroon, except for local hunters who purchase a permit to hunt for their own family’s sustenance. Since 1994, the country has had anti-poaching laws that are designed to protect its wildlife. But traditionally these laws have been laxly enforced; people continue to eat game meat in public without fear of repercussion, and conservation officers are sometimes paid off to allow hunting to continue. At the border town of Kyo Essi, for example, close to both Equatorial Guinea and Gabon, game meat is widely sold in markets and served in restaurants.

The social environment around these practices shifted when the Ebola outbreak began to unfold. Public messages about recommended safety precautions during the outbreak were mixed and confusing; a lot of information was disseminated via social media, where it wasn’t clear who was saying what. There was a lot of fear as well as pressure to keep the disease out of the country. To prevent Ebola from spreading into Cameroon, the government temporarily closed its border with Nigeria; established enhanced surveillance at 29 points of entry, including on roads, in airports, and at seaports; and installed procedures for the rapid reporting of Ebola cases. In the midst of all this, some public health messages told people not to eat bushmeat, supporting renewed efforts to police game-meat hunters and sellers. As one game-meat vendor told us, “During the Ebola crisis … I lost nearly all my bushmeat pepper soup customers.”

Research has shown that butchering wild animals is a high-risk factor for the spread of pathogens because it involves direct contact with the blood of potentially infected animals. Eating cooked, dried, or smoked wild game is another matter entirely; there is no evidence of anyone ever contracting Ebola from such meats. Yet the media extensively, and sometimes sensationally, cites bushmeat consumption in general as a cause of the spread of Ebola. In 2014, for example, Newsweek magazine reported, thanks to a conversation with a representative of the American Museum of Natural History, that it’s “very possible that eating infected, improperly prepared meat could spread Ebola.” Even in 2017, a press release on ScienceDaily asserted that “handling and eating bushmeat carries the risk of contracting diseases, such as Ebola virus disease.”

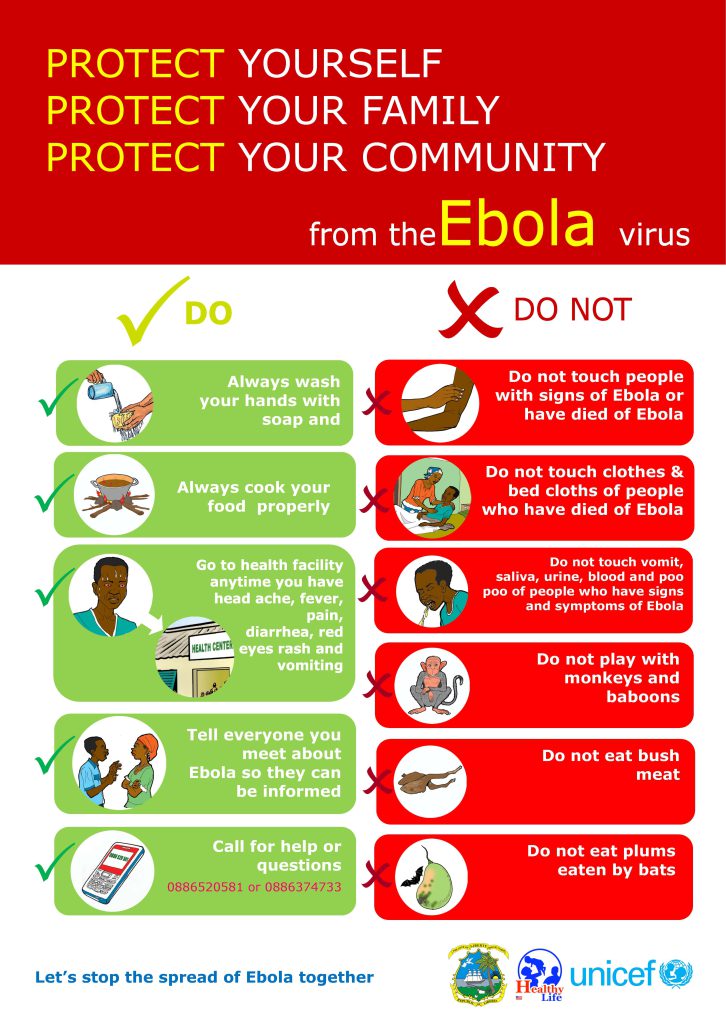

Even public health officials have sometimes circulated the message that bushmeat can spread disease. In 2014, Cameroon Public Health Minister Andre Mama Fouda announced that the fight against the Ebola virus must include engaging in frequent hand washing with soap and clean water, minimizing embraces, and avoiding contact with and consumption of bushmeat, particularly monkeys, chimpanzees, gorillas, antelopes, and bats.

Many locals have not been receptive to these messages. The practice of game hunting is an important part of their livelihoods. And they remember a long history of eating game meat without encountering any problems. They also have an extensive history of distrusting the government and officials: The criminalization of hunting wild animals in Cameroon is overseen by the Ministry of Forests and Wildlife, which many deem to be corrupt.

In 2015, a widespread belief began to emerge in the southern part of the country that the government’s anti-Ebola campaign was a hoax, driven not by public health concerns but rather by global conservation goals to stop the hunting, trade, and ingestion of game meat throughout Africa. As World Animal Protection’s regional director for Africa wrote in New Scientist magazine, “The Ebola outbreak is an opportunity to clamp down on a practice which both causes disease outbreaks and empties forests of wildlife.”

And locals cite many other reasons for being suspicious of conservation efforts and motives. The country’s hunting laws were developed in collaboration with international conservation groups—such as the World Wildlife Fund—that are run out of Western countries. Locals wonder why such non-Cameroonian organizations have had this level of influence and power. And they question who exactly these animals are being saved for: Western tourists, perhaps, or wealthy Western donors with a romanticized view of African wildlife? Thanks to Africa’s colonial history, animals ranging from elephants to lions have been thoroughly adopted by Westerners as beloved mascots of wilderness—so much so that cartoon versions adorn kids’ pajamas and frequently show up as favored plush toys.

In the view of some critics, Western conservation efforts in Africa are fed by neocolonial fantasies about saving Edenic Africa from itself. Outsiders often argue that treasured animal species are being threatened by Africans themselves. To the local people living among these animals—and relying on them for subsistence and income—the reality is much more complex.

The neocolonial perspective pervades how people in the West talk about game meat. The shooting of deer in the forests of developed countries generally is called “hunting,” while taking wild game in Africa, especially if it involves iconic species, is often labelled “slaughter.” The behavior of African hunters and game-meat consumers is often portrayed as shortsighted or even repulsive. It’s no wonder that local people often mistrust conservationist views.

As a result of local residents’ doubts and mistrust, public health workers in Cameroon are now concerned that it will be difficult to get people to believe crucial information about Ebola prevention. Trust in public health messages and adherence to public health measures have been noted victims of Ebola epidemics in other West African countries in recent years. Public health workers in Cameroon are worried that people will begin to disbelieve all infectious disease prevention messages, from the importance of washing hands with soap to minimizing contact with the deceased during burial practices. We are hoping to do more interviews in Cameroon to see if this is indeed happening.

Our research thus far shows that in order to regain trust, public health workers first need to be sure that their messages are supported by evidence and that their wording is precise: The issue of eating game meat is separate from that of butchering game. Second, they need to make sure they are talking with, and not at, their target communities. Their inclination is to say, “Do this and don’t do that.” But residents don’t come to those messages with a blank slate; their worldviews shape what they hear and what they believe. There is a lot of failure in public health messaging because this lesson has not yet been learned. There will be new Ebola outbreaks in the future; to minimize harm Cameroon needs a strong, well-trained, and community-sensitive public health system.