How Black Caribbean Communities Are Reviving an Ancestral Dance Tradition

As public discussions about social justice and Black resistance continue in the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd, an African American man, by a White, Minneapolis police officer last year, protestors around the world have filled city streets calling for structural changes that will protect and value Black lives. At the same time, Black communities are continuing conversations about creating safe spaces where members can continue to share knowledge, heal, honor their pasts, and build dignified futures.

Dance is one space for such community- and identity-building throughout the globe. In Martinique, for example, an island in the eastern Caribbean Sea, practitioners of bèlè, an ancestral dance practice, celebrate their African forebears and carve out spaces where they can incite conversations and action around individual and collective identity, expression, and healing through dance.

When Martinique, a former French colony, became an overseas department of France in 1946, Martinicans gained the same rights and obligations as French citizens. But the French government also tried to indoctrinate Martinicans by eradicating local traditions and ways of thinking and being, including bèlè, with the imposition of French modernization projects, institutions, and cultural programming. The trauma of assimilation in the ensuing decades has led to documented mental health problems within the Martinican population.

In this context, to dance or drum bèlè is to resist assimilation and to reclaim health, connection, and well-being. One of the people documenting this movement and its growing significance for practitioners is Camee Maddox-Wingfield, an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. She is a Black feminist scholar who studies dance anthropology, spirituality, and religion in the African diaspora with bèlè dance communities in Martinique. Her work invites people to think about community, resistance, and identity in new ways.

Maddox-Wingfield’s methods are somewhat unconventional for an academic researcher. She has learned to dance bèlè and rely on her own body as a research tool, and she brings dance and music to classrooms and conferences. She’s part of a rich legacy forged by Black anthropologists and other non-White anthropologists who have worked to create new ways of collecting and sharing data and stories beyond traditional written ethnographies. Trailblazers like Katherine Dunham and Pearl Primus, along with more contemporary visionaries, have used dance and other creative methods to push institutional boundaries and create safe spaces for Black women within the field of anthropology, which has historically been dominated by White men.

SAPIENS fellow and anthropologist Eshe Lewis spoke to Maddox-Wingfield via Zoom this February. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What is bèlè, and why is it significant in the context of Martinique?

Broadly speaking, bèlè is considered a drum dance tradition or a folk dance that is found in different parts of the Caribbean but with very different music and movement styles. These dances are usually based on European ballroom-style court dances that traveled to the Caribbean during the colonial era and then ended up integrating aspects of African movement, music elements, and footwork to different degrees—creating entirely new dance traditions. The bèlè that’s performed in Martinique is known to have retained and successfully integrated African elements more than any other version of bèlè.

Within Martinique, bèlè is undergoing a special revival—because it almost died out during an era of intense assimilation. So, today it’s celebrated as this cherished ancestral tradition. It’s not just a folk dance. It’s actually described in Creole as “an mannyè viv,” or “a manner of life.” It’s an entire lifestyle around which many grassroots performers and activists form their lives.

You say that bèlè almost died out due to assimilation after Martinique became an overseas department of France in 1946. What did assimilation look like in that period of the island’s history?

To be a good French citizen, you had to embrace all French institutions and values. The right to vote in French elections, and to have modernization projects and economic development, also came with institutions that played a huge role in assimilating people culturally. This included curricula designed to erase aspects of local culture in an effort to teach young school children French history and values.

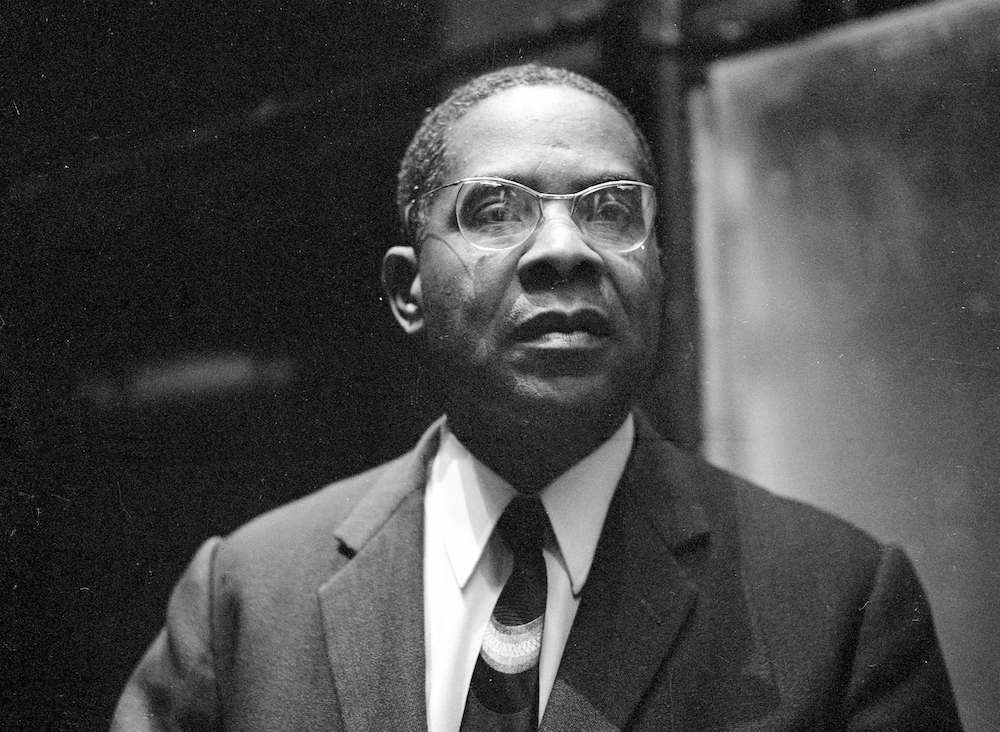

Aimé Césaire, who was one of the island’s leading intellectuals, the mayor of the capital, and the deputy to the French National Assembly, initially thought that becoming a French overseas department was a strategic maneuver for decolonization. He did not anticipate the cultural costs that would come with assimilation. Césaire later stated that he did not mean he wanted the French to fully substitute all the beliefs and ways of being Martinican. Césaire and Édouard Glissant, another Martinican intellectual, often described what they observed as a cultural genocide. And Frantz Fanon, who was a prominent postcolonial theorist from Martinique, made many of his anticolonial statements based on what he observed as a certain psychopathology that came with the colonial racism and the pressures of postcolonial assimilation.

These intellectuals alluded to the structural violence that has created severe mental health implications and crises over identity—what it means to be both French and Black Antillean, and what it means to continue in this ongoing state of colonization, where France basically makes all of the decisions about life in Martinique. The timeless commentary about the cultural cost of those pressures to assimilate is what now ignites many [bèlè] activists.

How do bèlè practitioners use dance as activism?

In February 2009, strikes erupted in Guadeloupe and Martinique, right around the time I was preparing a project about Martinique for my master’s degree. People were making demands for political change and airing their grievances around the economic realities of living in Martinique.

There is a racialized division of labor, where the descendants of slave planters still own all the property and the businesses, and workers’ salaries don’t reflect what it costs to live there. I was there as the island was trying to put itself back together after a 38-day period of suspension of all economic activity and large-scale unrest.

I found out that the bèlè community had been very instrumental in getting people out in the streets. By using the drum as a mobilizing tool, they were waking people up and getting them to say, “Now’s the time to make demands on the French state to lower the cost of living and raise workers’ salaries.”

With that came an opportunity for cultural activists who practiced bèlè to say, “Let’s also talk about the cultural alienation that we’ve also had to deal with as a result of assimilation.”

For many bèlè activists, speaking Creole, dancing bèlè, and playing the drum were not allowed when they were growing up. Bèlè was associated with the poor, rural working class, and these activists’ parents wanted them to be “good,” sophisticated French people. Many people I interviewed in that post-strike moment who had become involved with bèlè [for the first time] said they were inspired and motivated to learn more about aspects of their heritage that had been systematically discouraged.

They were impressed with how influential the drum could be in terms of bringing people together—not just to protest and undo these structures of oppression, but also to ignite joy.

Martinique is sometimes thought of as a political failure because it didn’t fight for independence like other islands in the region. How does bèlè offer a different way of thinking about what decolonization looks like today?

Every time Martinique has been given the opportunity to vote for more autonomy, the people have overwhelmingly voted against it. And that tells us that the people of Martinique don’t want or think they’re ready for political independence. So, they have to be strategic and really imaginative in terms of thinking about what it means to continue to belong to the French state but maintain their sense of cultural specificity and identity.

That means thinking in much broader terms about what decolonization can look like. And bèlè is a space where that happens. It gives people a new vocabulary and a new philosophical orientation to belonging to Martinique under the system of the French state. It also presents a new voice to make demands of the state to acknowledge their often undocumented contributions to French national culture.

Bèlè is now offered as an elective class for high school. That requires the standardization of the dance so it can be teachable to a large number of people, so that means kind of watering down some aspects of the dances to systematize them. But it is a way to get a French institution to acknowledge and integrate aspects of Martinican traditions, heritage, and values into a system that has long excluded them.

Your research explores the experiences of Black women who dance bèlè. Can you share what you’ve learned?

Black women have experienced different degrees of marginalization in Martinique: They are shamed for their sexuality, and they’re stereotyped as being dependent on French subsidies, social services, and welfare.

In bèlè, their sexuality and unique dance style is celebrated. The male dance partner does not determine the outcome of the dance encounter. He’s pursuing the female dance partner, and she’s the one who is either going to open her arms and embrace his pursuit or reject him and move away.

People feel a sense of trance or transcendence—altered states of consciousness and ecstatic joy—in this dance space. The women I work with are empowered and feel a sense of affirmation through bèlè that they say contributes to their healing and well-being. They say, “I can go out and face the hardships of my everyday life from Monday through Friday because I know there’s a swaré bèlè [a dance gathering] on Saturday night, and that’s going to make me feel good.”

It’s a form of therapy and self-care—not just because you’re moving your body and getting physically fit, but spiritually and emotionally, it’s a space where a lot of transformation happens.

Even during the pandemic, some people in Martinique have continued to practice bèlè, despite the public health risks. They gathered this year during Carnival, for example, the multiday celebration that marks the buildup to Lent. What do you make of that?

Right after the pandemic started, many of the planned annual activities around which bèlè is organized in a more formal sense were canceled. People had to practice masking, social distancing, and staying at home.

I think it’s been really hard on the people who rely on this communal activity that reflects a lot of their values—mutual aid and collectivity. In a society that has otherwise become very assimilated and individualistic, these are spaces where people—myself included—can reflect on and enact values that were important to our ancestors. And to have that completely taken away, it’s going to have its consequences. Deprivation and despair do that.

So, even though they weren’t supposed to have Carnival this year, they did. People were in the streets parading and marching and doing processions. Because for them—and I understand this argument well—Carnival is the time where you’re able to really purge and exorcise all of the frustrations and tensions; it is supposed to serve the well-being of the people in a collective way. For four days straight, you can just get it all out of your system.

In a similar manner, in the U.S., people went to protests for George Floyd. They knew what the risks were, but they said: “We have to stand up for this conviction and belief that his life mattered, and there’s the possibility that these cops will face impunity. So, I’m willing to risk getting COVID to go out to the streets and protest.” I think that protests have a similar function of giving people an opportunity to release pressure and frustration and other restraints that Black people have to navigate just to be, to just live peacefully. There’s so much pressure.

Protesting for George Floyd was a necessity for the Black community. I see Carnival the same way.

It’s a form of therapy and self-care—spiritually and emotionally, it’s a space where a lot of transformation happens.

There’s a long history of Black anthropologists, such as Katherine Dunham, studying dance and incorporating dance into academic spaces where it hadn’t been before. Why is that legacy important?

Katherine Dunham was someone who did not follow a conventional academic path. She did fieldwork in the Caribbean and took it to the stage and developed a dance technique, the Dunham technique, which combined modern dance and bèlè with African and diaspora movement traditions. She was not afraid to go to a panel of judges who would be awarding an academic fellowship and dance for them.

My mentor in graduate school, Faye Harrison, had previously been a dancing artist and performer, and she wrote about the legacy of Dunham and other Black anthropologists who found other ways of producing anthropological knowledge outside of what we know as ethnography. It’s what gave me the signal to pursue anthropology further and know that dance was going to be at the forefront of my work.

Following on Dunham, you have anthropologists such as Elizabeth Chin [Haitian folkloric dance specialist], Yvonne Daniel [dance performance and Caribbean societies specialist], Deborah Thomas and Aimee Meredith Cox [both former professional modern dancers], Gina Athena Ulysse [spoken word poet], and others who have used performance as a way of talking about issues anthropologists should be interested in, such as cultural politics, embodiment, resistance, identity, imperialism, and neoliberalism.

Not simply saying, “Here’s the data from my fieldwork,” but creating real interventions about important issues.

You practice dance in addition to studying it. How do you incorporate movement into your work?

I often describe my research methodology as: My body became the site of field notes, my body became the data collection tool—because it’s where the embodied muscle memory of things I needed to recall for my analysis were generated.

I danced at a panel at an American Anthropological Association (AAA) meeting a couple years ago. Performance creates an entirely different energy in the room and prompts people to ask other questions—for example, about affect and emotion, embodied knowledge, and connections across diasporic communities. That’s why when I talk about bèlè, I never think I can just share a paper or a chapter. No, there has to be a visual element—whether it’s a live performance or a recording or photographs—to show how people’s bodies move through space.

But even when spaces are created for us to come and perform in academic settings, you still have people who believe we shouldn’t be there and try to silence us. A few years ago, Elizabeth Chin and Aimee Meredith Cox and others did a performance at the AAA with a live drummer. Someone from the panel in the next room banged on the wall and said, “Stop the drumming!”

That says a lot about how far anthropology has come—and how far it needs to go.