Living With Parakeets and Other Migrants

When I came to Amsterdam as a graduate student in 2012, I was surprised to find the city’s parks teeming with vibrant green feathers, red beaks, and bluish tails. The birds, which looked to me like parrots, were hard to miss. They congregated in Vondelpark, close to the city’s famed museums and canals, and also in Oosterpark, where I jogged daily. Even without seeing their verdant plumage, I could hear their distinctive squeaking noises in the air.

Parrots, as far as I knew, were tropical birds—and often elusive. Even in my home country, the Philippines, where there are a number of endemic parrots, they’re a rarity, visible only to birdwatchers and hikers who go deep into the forests. Indeed, only when I took up birdwatching myself did I see some of them in the wild, making it even more astonishing to see so many in Western Europe.

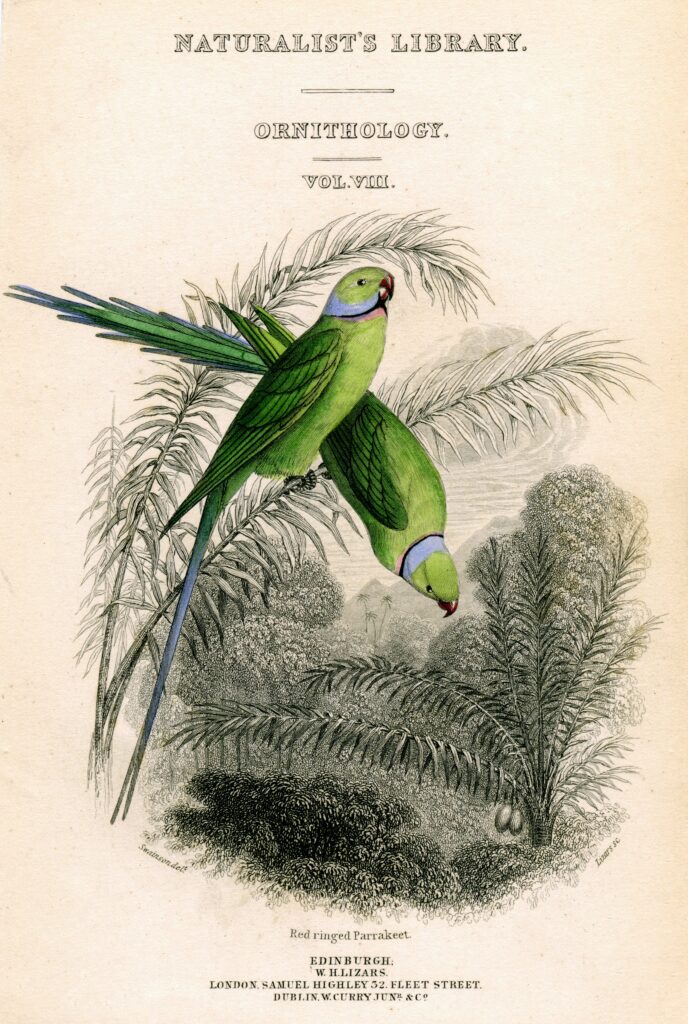

Soon I learned the birds were rose-ringed parakeets (Psittacula krameri), a type of parrot. The species is native to Africa and the Indian subcontinent, but the birds have made a home in Amsterdam for decades. In the dozen years I’ve been coming and going in the Netherlands, I’ve heard and read various urban legends about how the birds got established in the city. One widely circulated story says musician Jimi Hendrix released some of the birds in England, and they ultimately spread across Europe.

But experts agree the likely explanation is more mundane and harder to trace: Numerous parakeets either escaped or were released in the city beginning in the 1970s, when they were at the height of their popularity as exotic pets and were popular features of zoos and aviaries. These birds found one another, eventually forming the colony that survives, and thrives, today in Amsterdam.

Eventually, I grew to take them for granted as part of the cityscape, alongside the herons, swans, ducks, and coots (a dark-bodied waterfowl with a white forehead and bill). On a recent visit to Vondelpark, however, their nagging, but otherwise mostly welcomed, presence led me to ask: Why are some species accepted in places where they are not considered “native” while others are categorized as “invasive”?

At first glance, the answer seems simple: Anything that isn’t “native” is “invasive.” The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration defines an invasive species as one “capable of causing extinctions of native plants and animals, reducing biodiversity, competing with native organisms for limited resources, and altering habitats.”

But many species have traveled across the globe throughout human history, including as part of human trade and migration patterns, and not all of them are seen as problematic.

Especially when we broaden the historical scale of our question, the idea of species “nativeness” gets murkier. Recent introductions, like pythons in Florida, are seen as a problem, but eucalyptus trees in California, which arrived from Australia in the 1800s, receive more sympathy. Many of the flora and fauna we take for granted as part of our local landscapes may have been introduced during what historians call the Columbian Exchange, the global migration of different species facilitated by European exploration and colonialism from the late 15th century onward.

To these species’ defense, one might point out that it wasn’t their fault they ended up all over the world. Many birds have long been migratory, but avian species have been forced to migrate from their habitats to cater to colonial desires for the exotic. Like other non-native species first introduced as pets who were released or escaped from captivity, some bird species have managed to persist in new environments through a combination of behavioral and genetic adaptations.

Further complicating the idea of “nativeness” is the fact that climate change is altering the potential habitats of species. This makes our own species complicit not just in the adaptation of species to urban landscapes but in the transformation of ecological niches. Scientists speculate that the parakeets may have adjusted to European climates thanks to their exposure to Himalayan cold. Very likely, the Earth’s warming has also helped them settle in. These environmental pressures will likely facilitate more “migrations” or “invasions” of various species in the years ahead.

The ways people think and talk about nonhuman species often mirror how they think and talk about humans considered “others” or “outsiders” to their communities—including migrants. Racist and xenophobic political discourses often describe human migrants as unwanted “vermin” or “invasive insects.” Biological science, by using terms like “native,” “introduced,” “alien,” and “invasive” to describe nonhuman species, arguably (even if unwittingly) participates in this discourse. This kind of language can be used to justify efforts and proposals to control, remove, or even kill foreign “outsiders.”

In my experience, the parakeet migrants in Amsterdam have mostly been met with tolerance. People I know seem unbothered by the birds’ presence or even see them as fully integrated members of the city. One resident, who grew up accustomed to seeing them in the city parks, described them as “local birds.”

This acceptance of the parakeets seems to align with central values of Dutch identity such as freedom and tolerance. In 2008, a statue of 17th-century Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza wearing a cloak covered in rose-ringed parakeets, sparrows, and roses was unveiled in front of Amsterdam City Hall. According to medical anthropologist Eileen Moyer, the sculptor Nicolas Dings included this imagery “to invoke thoughts of cultural diversity and tolerance toward migrants.” Moyer, who is from the U.S., sees herself reflected in the parakeets. “They may be migrants to the city,” she writes, “but it’s quickly become their home.”

But the relatively welcoming attitude the Netherlands has long held toward border-crossers might be changing. Like many parts of Europe, the country has been steadily moving to the right politically. In October, the hard-right Dutch government approved a series of policies intended to severely restrict human migration; the legislation is awaiting approval from parliament.

It’s unclear what this might mean for Amsterdam’s parakeets. Public attitudes may be hewing closer to other European cities where there is perennial talk of culling this species. In the Randstad, the urban part of the Netherlands that includes Amsterdam, numbers of rose-ringed parakeets had reached an estimated 22,000 in 2022 from just over 5,000 in 2005.

Last year it was reported that the birds were causing higher energy costs by making holes and disrupting the insulation of houses and establishments. Others have raised concerns with parrots’ ecological impacts—including to native avian species.

For now, Vondelpark and Amsterdam’s other parks remain lively places, host to residents and visitors, natives and non-natives alike.

Some of the city’s locals have continued to defend the rights of the birds to remain. As Roelant Jonker of City Parrots, a local organization for urban bird conservation, put it: “If you really want our nature to be as it used to be, then we have to get rid of rabbits and pheasants as well as the European beech tree, which was introduced by the Romans. The one thing about nature is that it is always changing.”

Such arguments resonate with the work of multispecies ethnographers, who call for a more nuanced view of how species travel and interact with one another. Rather than relitigate the past and interrogate what counts as more “native” and “traditional,” they look more to what can be done in the present and future to acknowledge our entangled fates.

As anthropologist Eben Kirksey says, the challenge is “how to live ethically with those who share the world with us right now.”