Can the Holy Spirit Be Livestreamed?

Every Sunday, during her fieldwork, Cristina (one of the co-authors of this piece) would join hundreds of congregants under one roof as they connected with God and their fellow Christians. Time spent in church was emotionally intense, at times viscerally overwhelming, and always accompanied by the loud sounds of Christian music—heavy on the drums and spirit-filled singing. Congregants would regularly fall to their knees, their hands clasped tightly to their hearts, crying tears of joy or supplication. Many closed their eyes, raising their hands high in the air as if to reach out to God. Some slowly swayed side to side, allowing the music and sound of prayers to engulf them. Sometimes the pastor, sweaty with exertion, would lay his hands on those who came to him seeking healing.

Sunday worship captured what it means to embody faith, to physically connect to God and one another.

And then on March 15, 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, everything changed. The Australian government ordered a full shutdown of all but essential services—and churches were not on the “essential list.”

As services started to be streamed online, Cristina began watching them on her iPad, always alone and mostly while catching up on chores, at times losing track of the pastor’s message as she flipped between dinner’s online recipe and the pastor’s online preaching. Like those we later interviewed, she missed being together with others during the service, without domestic distractions, and being part of a vibrant worship community.

As anthropologists who live and work in Australia, we have been studying migration and religion for over a decade. We were just embarking on a new study of the role of Christian churches in African Australian communities when the pandemic hit. Our research, like the churches, went virtual.

In the past few months, we have conducted over 60 hours of interviews via Zoom with pastors and churchgoers. The emerging picture is one of benefits and challenges. The increasing use of online worship has allowed many churches to significantly increase the number of people who attend their services and to greatly diversify their congregations—including new congregants based in Africa and elsewhere in the African diaspora. But, at the same time, people were struggling to work out how best to worship and to feel connected to their faith in the absence of physical presence.

Across Australia, the pandemic has brought with it a broadscale resurgence of faith. During the first phase of lockdowns, from March to May in most of the country, a survey found that more than a third of the Australian population increased their prayer and other spiritual activities, with more than a quarter intending to continue doing so after the restrictions were lifted. (Australia isn’t alone: A study by the Pew Research Center found that a quarter of Americans felt that their faith was stronger because of the pandemic.)

This resurgence of faith has surely been boosted by churches’ transition from their usual face-to-face services to virtual engagements, which have a broader and often global reach.

Some churches, like the Australian megachurch Hillsong, had made intense use of internet-based and television worship for many years prior to the pandemic. Hillsong has branches in most global cities, 3.5 million YouTube subscribers, and an award-winning worship band whose music is sung weekly by an estimated 50 million people in 60 languages. (Its most popular song, “Oceans,” has been streamed more than 253 million times on Spotify.)

Yet a virtual engagement of this magnitude is the exception rather than the rule in Australia. Most other churches, especially smaller ones, needed to rapidly adopt and adapt to technologies such as Zoom, Facebook Live, and YouTube.

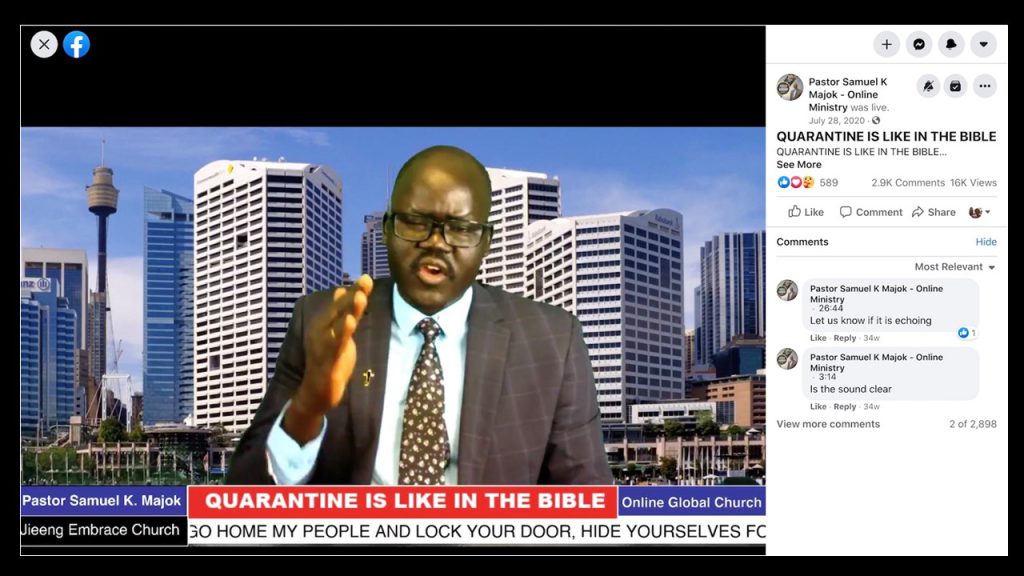

The main benefit of the online transition was for small churches that can now reach a much broader audience. For instance, a South Sudanese pastor based in Sydney told us:

“Last night I was doing online preaching and finished by praying for the sick people. The video has been viewed by nearly 4,000 people, 3,400 people commented, 250 people shared it. Personally, I don’t know them. They are all over Australia. Some are in the U.S. Some are back home in Africa, in South Sudan, Nairobi, in Dakar, too. They follow me on Facebook, and we pray together. They can call me through Messenger on Facebook, and then they say: ‘[Pastor], I need to pray with you, and this is my prayer request.’”

For these churches, going online has broadened their scope and their spiritual networks.

Many of the congregants we spoke to talked about how strange they found the experience of worshipping “through a laptop,” as one person put it. One young woman described how her mother had continued to make her “do her hair” and dress up in her finest clothes to attend the family’s weekly service, despite the fact that they now participated in this worship through a computer in their living room. The young woman had found the whole thing “just plain weird” and eventually stopped taking part.

A far greater issue for many of our research participants was the effect that the shift to online-only had upon their feeling the presence of the Holy Spirit.

The vast majority of the churches we have been researching are Pentecostal. Broadly speaking, Pentecostals seek a powerful and strong personal experience of salvation (being born-again), along with glossolalia (speaking in tongues), divine healing, exorcism, and prophesy. In recent years, the anthropology of Pentecostalism has shown how this form of Christianity is predicated upon worshippers’ feeling the presence of the Spirit—an experience that’s amplified by an embodied engagement with other congregants. During services, packed crowds sing, sway, and lay their hands on people who need healing. The online world of worship lacks this embodied engagement—and so the Holy Spirit can be harder to sense.

Several of our interviewees had developed techniques for trying to re-create a sense of bodily connection within the constraints of their lockdown. One young woman described how she had insisted on holding hands, and linking arms, with other family members, at least, while they prayed together. And the pastor of

Many of our participants were much more concerned about not being able to attend church than about COVID-19 itself.

one African-initiated church attempted to re-create the feeling of an embodied congregation by recording his Facebook Live services from within his church’s usual place of worship, alongside a handful of his church leaders (all of whom were suitably socially distanced).

Other challenges are more practical: Some people lack familiarity with particular technologies, live in rural areas with poor internet connection, or cannot afford decent computers or suitable home Wi-Fi. Some pastors endeavored to “plough on regardless,” despite patchy internet, pixelated streaming, and crackly sound. Others eventually abandoned internet-based worship in favor of more traditional media.

One church leader started burning DVDs and CDs of his online sermons, which he dropped off personally or mailed. Another eventually took to printing his sermons onto paper, along with accompanying prayers and relevant Bible passages, and distributing paper photocopies. Following lockdown, people were forced, sometimes for the first time, to swiftly and creatively engage other kinds of media.

African-majority churches play a central role for African diasporas in Australia. Churches are not just places of worship. They are pivotal institutions for their congregants’ social worlds, which provide spiritual, sociocultural, emotional, and material support. For many immigrants, the support offered by Australian social workers and counselors can feel like an intrusion; they are often used to living in tightly knit communities, where everyone knows everyone. Elders and church leaders are trusted mentors.

As one of our respondents put it, the first African-majority church she joined in Australia provided her with a sense of: “Oneness … you know, community, where it wasn’t just about worshipping together, singing the same songs, and speaking the same language, but also about carrying each other’s burdens.”

We were told many times by our participants that they were much more concerned about not being able to attend church, with all the trusted emotional and material support that it entails, than about COVID-19 itself. As this Sudanese pastor told us about his African-based congregants:

“They have seen terrible and horrible things, more than coronavirus … like Ebola, like HIV/AIDS or other deadly diseases. So, African people, we’re not very scared about it. … [Sudanese people] want to go to church, they want to go to church regardless. Even now in my village back at home, they want to go to church, but we are telling them as a church minister, to show my love for you, I have to let you stay at home.”

Christian churches have always embraced new technologies and media as tools for proselytization and worship—from mimeographed texts to photography, film, radio, cassette tapes, and TV programming. But the recent change in ways of worship has been remarkable both for the speed and the scale at which it took place, and for its effects.

These worship strategies are here to stay for some time to come. Although Australia is doing well in this crisis by global standards, it is still vulnerable to local lockdowns and increased restrictions when COVID-19 flares up. Churches flip between in-person and online, adapting services often in a matter of hours.

As our research has shown, African-majority churches in Australia have been greatly affected by the shift. Some churches have grown; others have struggled. Together these Christians are finding new—and rekindling old—ways to connect with the Holy Spirit.