What Makes a Refugee Vulnerable?

In the Dagahaley refugee camp in northeastern Kenya in 2012, I met a Somali woman who told me that her husband had disowned her and their children so they wouldn’t endanger his resettlement prospects.

She hadn’t seen her husband since 2008, when heavy fighting in her Mogadishu neighborhood separated him from the rest of the family. The family was briefly reunited when the woman and her four children sought asylum at Dagahaley in 2012, and she discovered that her husband had been living there all along. She also learned that he was being considered for resettlement on the basis of having lost his family to the civil war in Somalia that has driven tens of thousands of people across various international borders. When she pressured him to include the entire family in his resettlement process, she told me, he threw them from his house and told officials at the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) that they were imposters. Apparently, he felt his chances were better without them.

In August 2011, I set out as an anthropologist to study how local Kenyans had coped with hosting refugee camps for two decades. After starting my fieldwork, however, I was struck by a strange and unfortunate phenomenon. The thing that kept people going in the camps was kinship: Somali locals and refugees forged relationships that went beyond the camps. They connected for friendship and family, food and medical services, trade, and access to animal pastures. Yet the UNHCR perversely discouraged such productive relationships by prioritizing resettlement for long-term residents with no connections—those who were deemed most “vulnerable.” In other words, the system effectively penalized refugees for carving out a better life.

The very act of selecting who is most “vulnerable” encourages refugees to stay vulnerable. This strategy does not help them move forward with their lives. Throughout my year-long fieldwork, I heard many dramatic stories of people pulling out all the stops to display vulnerabilities that would qualify them for resettlement—including denying the existence of their family. These insights should move us to rethink how we can actually help refugees rebuild their lives.

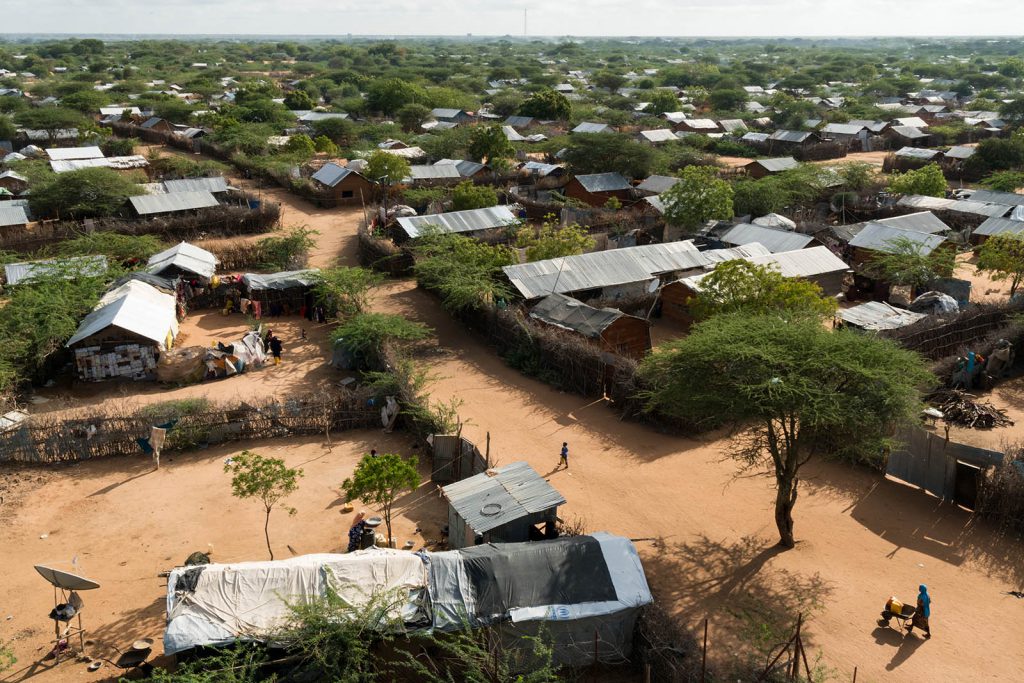

Dagahaley is part of what is commonly referred to as the Dadaab refugee complex: a set of four camps clustered around Dadaab town in Garissa County. These camps, set up following the outbreak of war in Somalia in 1991, were home to over 450,000 refugees during my fieldwork.

The line between refugees and locals in and around these camps is blurry. The camps are located about 75 kilometers from the Kenya-Somalia border, which has historically been ignored by Somali nomads on either side of it. Because of the centuries-old interactions across the Kenya-Somalia border, refugees came to Kenya already enmeshed in relationships with their hosts; there are Somalis living both inside and outside the camp walls. Although refugees are officially not allowed to move beyond Dadaab, those who can afford to bribe susceptible police officers can easily move in and out of the camps. Wealthy traders, for example, constantly travel to Somali and Kenyan urban centers to buy and sell their goods.

During my work, I saw that the UNHCR and its implementing partners provided refugees with barely adequate food rations, along with basic medical and educational services. Most people supplemented their rations with remittances they received from relatives who had been resettled in Western countries. The money transfer shops that administer these remittances had visibly transformed camp towns into centers of intense business activity. There was, in fact, a widely held view among government officials that Somalis did not resemble proper refugees because of how remittances had enabled a considerable number of people to run thriving enterprises. But generally speaking, most refugees led basic lifestyles: They were housed in tents and mud-walled structures, and they had few opportunities for improving their lives. In addition, they lacked political rights.

Resettlement—the act of selecting and moving refugees to a new place where they can acquire permanent refugee status and integrate into society—is an incredibly attractive option for those living in these camps. With the long-term goal of returning to Somalia when conditions improve, many people believe that they will be in a better financial position to make that transition if they first resettle in a Western country. But resettlement is elusive: According to the UNHCR, in 2014, only 1 percent of the refugee population in Kenya was resettled.

Officials need to have some criteria for deciding who is most vulnerable and should be prioritized for resettlement. However, the metric of measuring vulnerability seemed unstable and arbitrary to the people I met in Dagahaley. They recalled how rape victims were by far the largest beneficiaries of resettlement decisions in the mid-1990s. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, however, what counted more was being part of an oppressed minority group. Other times, the decisions seemed completely inexplicable: In 2006, they told me, a local politician was resettled despite being an elected official in the municipal assembly.

During my fieldwork, there was a general consensus that the UNHCR was prioritizing long-term camp residents over new arrivals. For many, this seemed an appropriate thing to do. But it also perversely encouraged suffering as a kind of necessary rite of passage. As one long-term camp resident told me, “We have suffered for 20 years, and our children also need a good life. Those who came recently should stay here for some time, like we have done, before being considered.”

The UNHCR was also disqualifying people who had longstanding community connections, saying they were fraudulent cases: People with family in Kenya, for example, were considered to be already integrated into society and not in need of further aid. In one situation, a person I met had been housed at a UNHCR compound following repeated attacks on his family because of his minority racial status. At first, the UNHCR categorized him as an urgent case for resettlement, but they later canceled the process when a computer database showed that his wife had a Kenyan ID. His vulnerability evaporated overnight, and the UNHCR ordered him to vacate its compound and return to the camp.

The refugees I met faced a dilemma: The best way to leave the camps through resettlement seemed to be to stay there ever longer, without forging any connections. But there was a distinct and persistent possibility that priorities might change and render this long-term, difficult effort meaningless.

Families in these camps were often separated as a consequence of UNHCR policies. A case in point is Amin Amey, who was in his 20s when he reported having been separated from his parents in 1991 when he was 9 years old. He later reunited with his mother, but he was separated from her again when he was resettled in Sweden. According to a report in The Refugee newsletter, a publication that circulates in the camps, “The dream that Amey waited for two decades finally became true when the UNHCR contacted him about his departure to his new home, Sweden. … However, Amey’s final days in the camp were also filled with [a] mixture of happy and sad emotions. His mother, who was missing without a trace for 15 years, reunited with him only days before this departure. Amey said he couldn’t include his mother because she is not a registered refugee.” It is quite likely that Amey was actually reunited with his mother earlier and that he had kept their relationship a secret for fear of it derailing his resettlement.

Others were motivated by circumstances to lie and cover up their relations in order to reinforce their vulnerabilities. Noor (a pseudonym), for example, had a sister whose family had been hurriedly evacuated to a European country amid heavy fighting in Mogadishu in 2005. They left behind her husband’s second wife and children. Eventually, the brother-in-law’s second family was cleared to join the rest of the family in Europe, but prior to their departure, they perished in a shell attack. This tragic incident provided a precious opportunity that could not be wasted: Following his sister’s advice, Noor asked his own wife and child to assume the identities of the dead so they would be granted passage to Europe. They did so, leaving Noor behind.

Noor hoped to follow, but five years later, his resettlement was still elusive. When I visited him in 2012, he had just received the sad news that his wife was requesting a divorce so she could marry a man she had met in Europe. At first, he refused to grant it, but he later consented when he realized that his “vulnerability” as the only surviving member of his family would come under scrutiny if officials discovered the existence of his wife, who had assumed a different identity. This seemed more likely if he prolonged the divorce negotiations.

Because of the long history of cross-border interactions between refugees and locals, it was almost impossible for refugees not to have connections outside the camps. The UNHCR guidelines prompted people to mask or undermine these connections, which made their lives more difficult. As another example of this problem, refugees who had integrated into Kenyan urban centers would regularly travel back to be confirmed as camp residents during refugee verification exercises, disrupting their lives for the sake of appearing more vulnerable.

Humanitarian policies do not often map perfectly onto the way people manage their lives. That perhaps cannot change. But organizations like the UNHCR should pay more attention to local nuances and complexities, and attempt to minimize the unintended and undesirable consequences of their policies. The most vulnerable of our societies should not be encouraged to invest in preserving their vulnerabilities.