Communities Grapple With Exposure to “Forever Chemicals”

Every summer, Ruth and John Kowalski saw clouds of thick, dark smoke rise above the tree line. “For 40 years, there’d be black plumes coming up every day,” John recalls.

The plumes drifted from a firefighting training facility in Marinette, Wisconsin, a city of roughly 10,000 people. Year after year, firefighters from around the world came to the Fire Technology Center to learn to use aqueous film-forming foams (AFFF). These foams extinguish flames fed by highly combustible substances such as jet fuels, petroleum greases, tars, oils, gasoline, and other industrial solvents and alcohols.

As the smoke cleared, foam residue soaked into the soil or seeped into local streams. Some was flushed into the sewer system, eventually turning up in Marinette’s wastewater treatment plant as a white froth so thick it blew around in the wind.

The Kowalskis live in the Town of Peshtigo, a wooded community just down the road—and downstream—from the fire school. Ruth works in education; John is a retired pipe fitter. They had barely paid any attention to the smoke and the foam—until a letter arrived in the mail.

It was sent by Arcadis, a multinational consulting firm hired to investigate groundwater contamination. The letter alerted Ruth and John to possible pollution of their well water from something they had never heard of: per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). These chemicals are key ingredients in the film barrier created by AFFF to smother a fire and prevent reignition.

The letter invited them to attend a meeting to learn about PFAS. And that was when the Kowalskis started thinking about health.

Ruth had recently been treated for thyroid disease, while John had faced prostate cancer. Memories of their children’s inexplicable health issues came flooding back. They pondered their grandchildren’s illnesses and developmental challenges. Ruth’s mother had had thyroid cancer, and now her 10-year-old granddaughter has thyroid disease. Several neighbors had suffered from cancers and unusual maladies.

Ruth and John were distraught. They had likely all been exposed for years. Suddenly, they found themselves trying to make sense of life in a contaminated community.

I am a cultural anthropologist who studies social life in a world saturated with industrial chemicals. I interviewed Ruth and John as part of ethnographic research I’m conducting in Midwestern communities that are on the front lines of a growing contamination crisis that affects everyone.

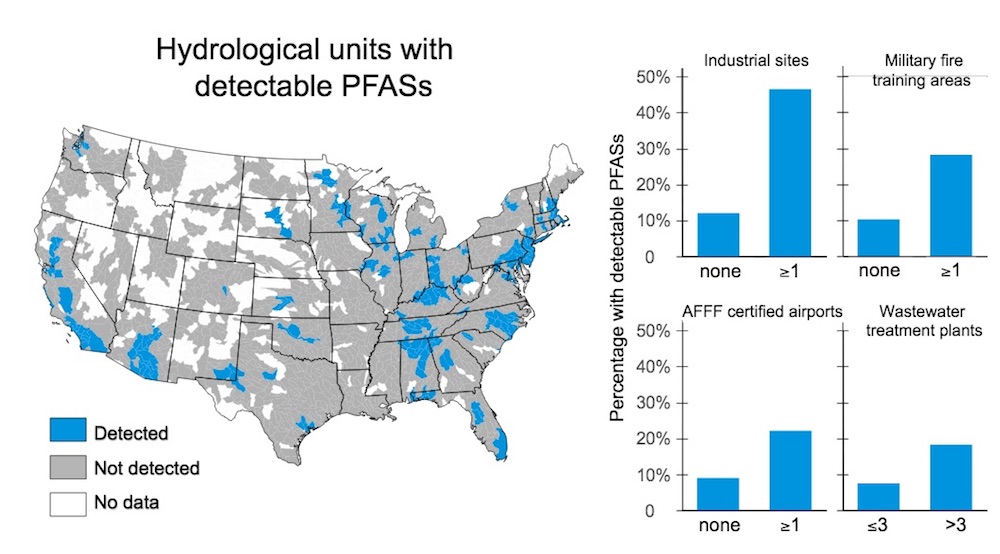

As of July, the Environmental Working Group has mapped more than 2,230 known PFAS contamination sites across the United States. The nonprofit estimates that up to 110 million Americans drink tap water tainted with PFAS levels that range from 2.5 parts per trillion (ppt) to levels that exceed the Environmental Protection Agency’s recommended limit of 70 ppt. (Several other health entities recommend significantly lower safety thresholds, as little as 0.1 ppt.)

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has found PFAS in the blood serum of “nearly all of the people tested,” meaning these chemicals already occupy the bodies of virtually everyone in the United States, regardless of whether one drinks polluted tap water.

Manufactured since the 1940s, PFAS represent over 4,700 industrially derived substances that repel or resist heat, oil, grease, and water. PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid) and PFOS (perfluorooctanesulfonic acid) are two of the most prominent of this family of chemicals and once were key ingredients in coatings such as 3M’s Scotchgard and DuPont’s Teflon. PFOA and PFOS, as well as variations of these, have been used in a stunning range of commercial applications.

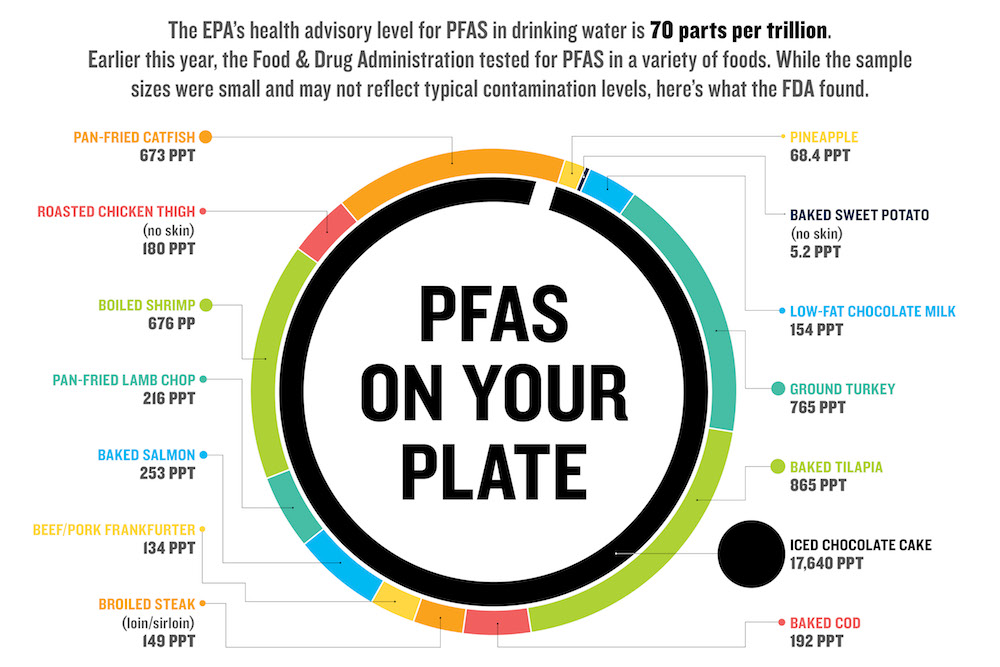

In addition to firefighting foams, PFAS lurk in a head-spinning array of products: food packaging such as pizza boxes and microwave popcorn bags; water- or stain-resistant clothing, shoes, and camping gear; furniture fabrics; nonstick cookware; paints and floor polishes; dental floss and cosmetics—the list goes on and on.

For many decades, PFAS were assumed to be safe and federal regulations such as the Toxic Substances Control Act of 1976 grandfathered in chemicals already in use. Even though manufacturers such as 3M and DuPont began studying the potential hazards of PFAS as early as the 1960s and documenting human exposure among their workers in the 1970s, they only partially disclosed their findings to regulatory officials, in some instances concealing their studies from the public. It is only in the last two decades that litigation has revealed some of 3M’s and DuPont’s internal health studies, raising concern in many communities and sparking an explosion of interest among scientists and state regulators.

As scrutiny mounted, 3M announced in 2000 that it would phase out PFOA and PFOS. Following a class-action lawsuit and a US$16.5 million settlement with the EPA in 2005, DuPont also agreed to phase out use of PFOA.

Despite their discontinuation, however, the toxic legacy of PFOA and PFOS will outlive all of us. PFAS have been dubbed “forever chemicals” because they accumulate in living organisms, including people, and persist for an extremely long time in the environment. Some never fully deteriorate.

Contamination is commonly found near manufacturing or disposal sites and around many airports and military installations where firefighting foams have been used, often in training exercises. People may also be exposed through interaction with ordinary consumer products.

But, really, no one will escape PFAS. Not only are these bioaccumulating chemicals pervasive and persistent, they are highly mobile, traveling with surface and groundwater, air emissions, and even with rainstorms. They’ve been found in animals and people worldwide. And because they are in the water, in packaging materials, and in sewage-derived fertilizer, they’re also in food—everything from catfish to milk to chocolate cake.

And scientists are just starting to scratch the surface of how such widespread exposure affects humans. Some are troubled by the fact that extremely low concentrations of PFAS are associated with a wide range of health problems. One of the largest epidemiological studies ever conducted, between 2005 and 2013, linked PFOA exposure in contaminated communities near DuPont’s manufacturing plant in Parkersburg, West Virginia, with testicular cancer, kidney cancer, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia.

In addition, a large number of epidemiological studies conducted on both highly exposed individuals and the general population suggest an association between PFAS and liver damage, asthma, decreased fertility, reduced antibody response to vaccines, and other health problems, according to a report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The effects of low-level PFAS exposure in the general population are unknown.

A growing number of lawsuits have continued to bring industry documents to light and spark new health studies, as well as yield significant financial settlements. For example, in 2017 DuPont agreed to pay US$670 million to settle over 3,500 lawsuits related to health impacts suffered by residents near their Parkersburg plant. 3M settled a lawsuit with the state of Minnesota for US$850 million in 2018 to address widespread groundwater contamination linked to dump sites associated with its manufacturing plant near St. Paul. The companies, of course, deny wrongdoing in the settlements and downplay health concerns.

The EPA now considers PFOA and PFOS “contaminants of emerging concern,” but they remain unregulated at the federal level, and agencies such as the CDC are only studying a handful of the thousands of PFAS chemicals that exist.

Companies such as 3M and DuPont simply replaced PFOA and PFOS with alternatives, which some observers find alarming. In 2015, over 200 scientists signed on to the Madrid statement, which calls for limiting production and use of PFAS chemicals (both long-chain versions and shorter-chain options, which are often used as alternatives) until they are better understood, even those deemed “safe” by industry.

Despite such statements, new PFAS variants are being created yearly, adding to the thousands in existence and leaving regulators scrambling to understand their impacts.

“Hopefully, those chemicals are not as toxic,” I heard Patrick Breysse, director of the CDC’s National Center for Environmental Health and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, say at a conference in March 2020. “But there is no guarantee.”

The Fire Technology Center goes back generations in Marinette, a former lumber mill and port town nestled along the marshy shores of Lake Michigan’s Green Bay. Some locals still associate it with the Ansul Chemical Company, founded in 1915 to produce sulfur dioxide as a refrigerant. Over several decades, Ansul shifted to fire extinguishers and, for a time, herbicides, including Agent Orange.

By the 1980s, Ansul focused predominantly on fire-protection systems and was bought out by Tyco International, itself acquired in 2016 by Johnson Controls International (JCI), headquartered in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. In the early 1960s, Ansul began testing and training with firefighting foams at what is now the Fire Technology Center, a complex of buildings at the center of 380 acres of forested land near a high school, shopping centers, residential neighborhoods, and a hospital.

Scientists are just starting to scratch the surface of how such widespread exposure affects humans.

According to JCI/Tyco’s own documents, they were aware of PFAS contamination on their property as early as 2013. The company claims it did not have reason to believe the PFAS could affect the surrounding community. Then in 2016, they detected contamination at their property line.

In November 2017, JCI/Tyco announced the chemicals had spread farther, and the company stopped spraying foam outside. Testing revealed groundwater contamination in some locations ranging up to 254,000 ppt for PFOA and up to 64,000 ppt for PFOS. Samples of surface water, including two ditches or streams that drain into Lake Michigan, ranged up to 6,000 ppt.

The Fire Technology Center is connected to Marinette’s water system, which draws from Lake Michigan, but hundreds of homes within a few miles and mostly in the Town of Peshtigo rely on groundwater. Fifty-eight out of 168 drinking water wells tested positive for PFAS, with 16 homes exceeding the EPA’s recommended limit of 70 ppt.

JCI/Tyco began offering bottled water to residents in the area under investigation and installed dozens of point-of-entry filtration systems in households. As a long-term solution, they have proposed connecting impacted Peshtigo homes to Marinette’s water system.

Company officials cast themselves as acting “quickly” and “proactively.” But critics, including former Marinette Mayor Doug Oitzinger, say they should have suspected the toxins would spread and accuse JCI/Tyco of downplaying the hazard.

The issue initially drew muted attention in the broader community. But a year after the discovery, scrutiny of JCI/Tyco intensified. A group of residents criticized the slow reaction from the state Department of Natural Resources (DNR), which oversees cleanup of contaminated sites, and the lack of urgency among local elected officials. Residents organized, calling themselves “Save Our H2O” (S.O.H2O).

Local organizing intersected with the election of Democratic governor Tony Evers, who declared 2019 the “Year of Clean Drinking Water” and initiated efforts to study and regulate PFAS exposure in Wisconsin, a process expected to take years. An emboldened DNR referred JCI/Tyco to the state Department of Justice for failing to report the release of hazardous chemicals. The Wisconsin Department of Health Services recommended setting a PFOA and PFOS drinking water exposure limit of 20 ppt.

With prodding from S.O.H2O, the DNR began to confront the complex exposure pathways of these persistent and mobile chemicals.

“If this were petroleum, or many of the other contaminants that we work with in the environment,” explained Christine Haag, the director of the DNR’s remediation and redevelopment program, at a public forum in January 2020, “we could say that groundwater flow is a big predictor on where this contamination ends up. That’s not the case with PFAS. There’s volumes and volumes of things that the world does not understand about PFAS. But one of the things that most people can agree on is that this doesn’t behave like anything else in the environment. Therefore, the traditional ways we investigate contaminants doesn’t work in this situation.”

Marinette tested the biosolids created during the treatment of wastewater flushed into the sewer system. After processing, biosolids are spread as fertilizer on farms throughout the region. The material tested positive for “significant levels” of PFAS. At least since 1996, biosolids were applied to hundreds of acres across several townships, delivering PFAS contamination well beyond the Fire Technology Center. In the spring of 2020, JCI/Tyco began providing bottled water to three homes with wells likely contaminated from biosolids spreading on farm fields.

In addition to groundwater, surface water, and biosolids spreading, the DNR is now evaluating potential spread of PFAS pollution through air pathways.

As DNR administrator Darsi Foss acknowledged: “I think we thought this problem was, from an environmental standpoint, a little more isolated and more on Johnson Controls-Tyco’s property. And it keeps just growing and growing.”

Research on the health impacts of pollution is often contested, since it is extremely difficult to pin down how much exposure to a specific substance directly causes a particular disease.

The DNR has directed JCI/Tyco to also investigate groundwater contamination extending beyond the initial plume emanating from the Fire Technology Center, discovered when residents tested their wells on their own. JCI/Tyco has refused, claiming someone else may be responsible. Despite denying responsibility for the full scale of PFAS contamination in the region, JCI/Tyco told shareholders it has set aside US$140 million to address the problem over the next several years.

How do residents cope with and attribute meaning to the expanding PFAS crisis? As has been documented in other “contaminated communities,” toxic exposure is often confusing and deeply stressful, upsetting people’s taken-for-granted beliefs about health, the environment, and basic community structures.

Ruth and John Kowalski struggle with the uncertainties that accompany PFAS, not knowing to what extent they’ve been exposed. Initially, the well water at their house tested negative for PFAS, even though a shallow well in the yard tested positive, as did wells at their neighbor’s homes. “One house can be contaminated, the next one a non-detect,” said John.

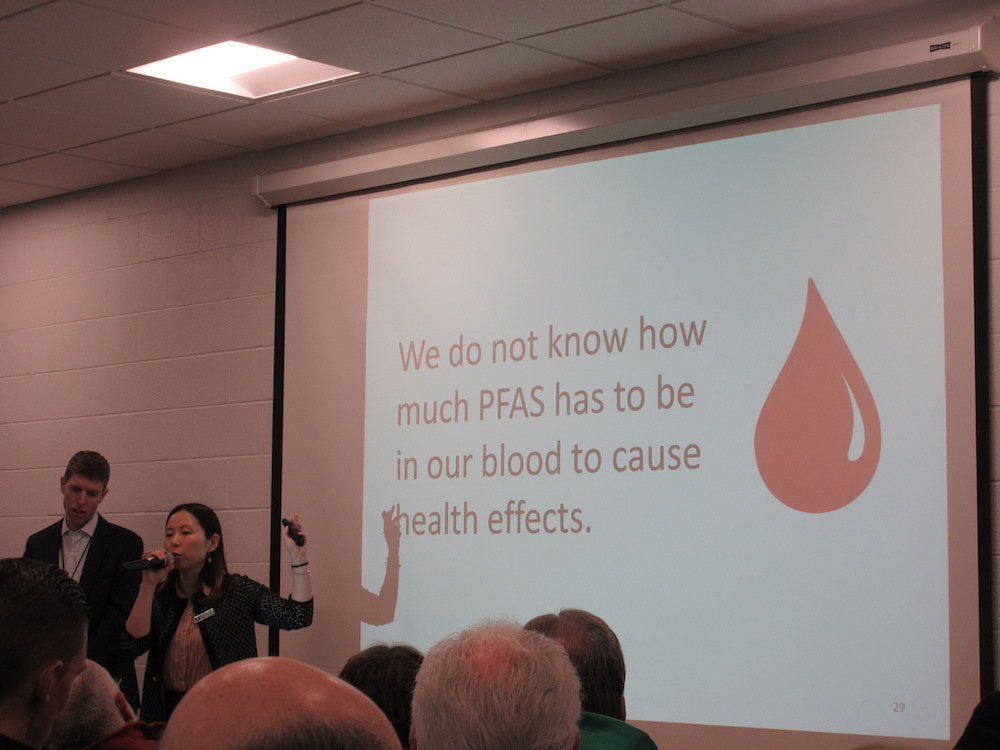

They are dependent on Arcadis—experts hired by the people who caused the pollution—to reveal hidden contamination, a situation that invites distrust. “I’m not sure who I can believe,” explained Ruth. She sought blood testing to find more definitive information. But health care providers were unfamiliar with the issue, and it took several weeks to find a lab to conduct an analysis. “Well, this is so new that my physician, and the lab, couldn’t even tell me what it meant,” said Ruth.

Her sense of vulnerability is exacerbated by state regulatory officials’ mixed messages. Even though they acknowledge a real risk to human health, the Department of Health Services maintains that blood levels cannot be reliably linked to specific health outcomes, which may have multiple causes.

Research on the health impacts of pollution is often contested, since it is extremely difficult to pin down how much exposure to a specific substance directly causes a particular disease. Laboratory studies expose animals at high doses in a controlled setting and don’t easily translate to social worlds where humans are exposed at low levels, in different ways, over many decades. Even workplace exposure occurs under specific conditions, making it complicated to apply such findings to a broader community.

The DHS says the health research on PFAS is just not there yet, and it may be decades before it is. In public forums I observed in December 2019 and January 2020, DHS officials discouraged residents from pursuing blood tests, since information about blood PFAS levels cannot guide health care treatment.

Ruth and others thus face a confounding scenario: They are told that PFAS pose a serious problem in need of immediate remediation but that they shouldn’t associate their individual health issues with PFAS exposure.

The Kowalskis’ home, which is on several acres of land with an apple orchard, a garden, and a pond, has belonged to John’s family for decades and was once a place of sanctuary. Their children used to play in the creeks that run past the Fire Technology Center, and John recalls seeing foam and a sheen on the water. “I never really thought about where it was coming from,” he says.

Today everything is suspect, a potential hazard. The presence of PFAS has scrambled the comforting sense of order and security associated with home. “I wouldn’t eat an apple off that tree,” says Ruth, pointing to the backyard. Ruth and John are also afraid to drink or cook with the tap water, and Ruth feels personally responsible for putting her children in harm’s way. “I’m assuming this is like lead,” she said, holding back tears. “When you have children, if you have high concentrations, then you poison your babies.”

Other residents are also reexamining past experiences and questioning their assumptions about life in Marinette and Peshtigo. As Annie Boyle Davis explained to a reporter, “When we were little kids, we would say to my mom, ‘Mommy, it smells like Ansul.’ It was just this horrible smell, and we just called it ‘Ansul.’ It was probably the way the wind was blowing and what they were making. … One day we went to school, I want to say it was 1970, and all the foliage around the school—the trees, the leaves, the grass—were dead.”

Another resident, who grew up across the Menomonee River from the Ansul plant, recalled the same time period—a summer when the trees in their yard had no leaves. At a public meeting in December 2019, she said: “We had continuous bloody noses, sore throats, blood coming out of [our] ears. The stench was so bad when the wind blew across the river that we had to keep our doors closed. We didn’t know what was going on. We were told not to make any waves because the chemical company could move away and take all the jobs with them.”

These days, she says: “I believe it was due to the chemicals we were breathing. The trees didn’t lie.”

As residents struggle to make sense of PFAS contamination and other industrial pollutants, one thing is clear: They are beginning to view exposure as a collective experience. Like Ruth and John, many once ignored the smoke that periodically drifts from the Fire Technology Center. It now signals a threat to community well-being.

“For years,” explained one former resident in a Facebook post, “the plumes I watched rise above the trees behind my grandparents’ woods brought me a sense of pride. Pride because all of the fire extinguishers my parochial grade school in Chicago used were from Ansul. … Now it is with shame that I remember how I told all my friends that I knew where that was made.”

She went on to describe feeling “uncertainty for my own future health” and “dread for what my own children, their children, aunts, uncles, cousins, and family may face in the future.”

At recent public forums hosted by the DNR, dozens and dozens of residents shared heartbreaking stories about health problems they fear might be connected to PFAS exposure. While anecdotal, such public statements transform the typically private, individual plight of illness into a form of social suffering, something around which to mobilize collectively. The DHS has indicated it is now conducting a cancer cluster assessment of the area.

One attendee at a January 2020 forum was Craig Koller, a 21-year-old who has endured three different forms of testicular cancer. “Part of me has always known,” he said to the packed crowd, “there’s something in the water.”