Egyptology Has a Problem: Patriarchy

The patriarchy hides in all kinds of unexpected places. It rears its head in Egyptology interest groups from Colorado to Texas. It lurks on “bro” radio shows. And it dwells in the attitudes of business leaders who serve on local museum boards. I know this because groups like these often perceive my observation that many of our world leaders are like the populist Pharaoh Ramses II as akin to treason.

When I speak with these groups, my talks are not what they are expecting. After all, these people love ancient Egypt; they have a passion for the past, even collect Egyptian antiquities and watch a lot of Discovery and History Channel.

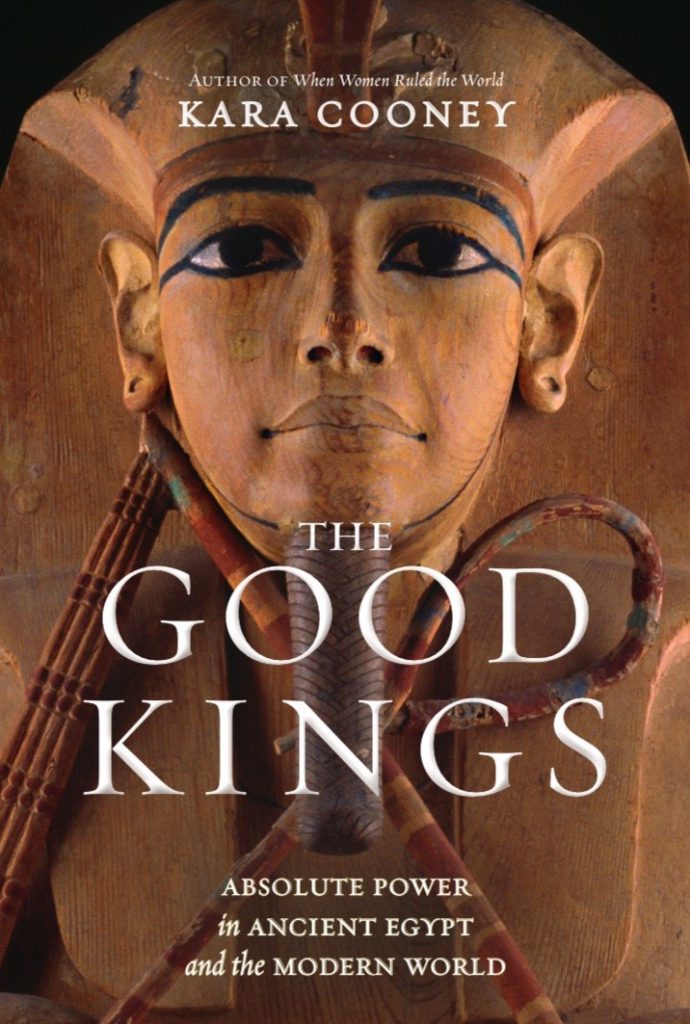

So, it makes sense they might be interested in my latest book, The Good Kings, which examines autocracy in ancient Egypt and today. The book explores how pharaohs propped up their power by spinning narratives that continue to manipulate people into supporting patriarchy and authoritarianism.

Read an excerpt from The Good Kings: “What Egyptian Pharaohs Can Tell Us About Modern Tyrants“

Egyptology fans’ anger over this perspective is palpable. What right do I have to criticize these great kings? One man shouts over Zoom that American patriarchy defeated the Nazis, so I must therefore support the Nazis. They tell me I should stick to Egyptology: “Let’s get back to Egypt,” they admonish, with an obvious tone of displeasure.

They ask me which kings I consider “good” then, given the title of the book, and when I try to explain, again, that the title highlights the ability of ideology to make us all submit to autocrats as the only moral choice of leader, they ask me what is wrong with such leaders.

I say that the suit and tie of the entrepreneurial politician wielding righteous capitalism can be compared to the crook and flail of the crowned pharaoh, lord of Ma’at (ancient Egyptian for “order,” “right,” or “truth”). They protect demagogue showman Ramses II with the same fervor as they do Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee; I must not be allowed to tear those men down. They divinize the tyrant Akhenaten as they do former President Donald Trump. Akhenaten’s altars heaped with food offerings to the sun (seemingly left to rot instead of feeding the people) were not wasteful; I must be misunderstanding what actually happened at el-Amarna.

Their voices are minority privilege expressing fierce disappointment in me, a White woman who should be on their side, who should celebrate my partnership with them because it benefits me so much. Some ask me if I am going to give up my cushy professorial position to an Egyptian person, or a Black person, if I am so woke.

They tell me that my conclusions are wrong, that the patriarchy provides for me, and that my parents in Houston didn’t suffer that much when their heat was shut off during a cold freeze after rampant capitalist deregulation. They say I am exaggerating the harm that patriarchal structures have done to our environment, that there is no other way to run the world, and that without these good, strong men, there will be apocalypse.

One critic told me these things from his personal home theater filled with plush red velvet seats, where he had covered the walls with Egyptianizing motifs to show his great love of his Orientalized pharaohs. He exhibited decisive and masculine strength in order to demand my meekness and politeness, forcing me to acquiesce to his good rule. Such older White men interrupt me and roll their eyes, admonishing me to stick to what I know and not go into “politics,” where I have no place.

These are people who expect the binary: If I am not with them, then I am absolutely and completely against them. There is no nuance.

These people who love ancient Egypt often worship the same modern systems that maintain minority, celebrity rule.

My views seem to have touched a nerve. There is fear among these people—fear of change, fear of losing power, fear of recognizing the water in which we swim for the patriarchal smash-and-grab that it is. My joke about Jeff Bezos and his US$300 billion fortune (because what is a king if not that?) falls flat; some of them think they are like Jeff Bezos.

And I realize that these people who love ancient Egypt so much often worship the same modern systems that maintain minority, celebrity rule throughout the world.

Thus, we witness autocracy hiding in a quotidian Egyptological interest group or at a museum talk or in my social media spaces. Such truths, apparently, have not been uttered previously here—because who would dare? After all, we are so polite.

And as it turns out, we—all of us—have our own confined arenas, whether, for example, it’s Egyptology, Uber driving, law, caregiving, teaching, Amazon shelf-stocking, medical expertise, or science. And these spaces are guarded by people—usually men, though not always—who want to preserve longstanding power dynamics and tell us they know best.

But the time has now come to make these narrow spaces wide—so expansive and open that they can become beautifully complicated and contentious, political and full of change.