Grappling With Guilt Inside a System of Structural Violence

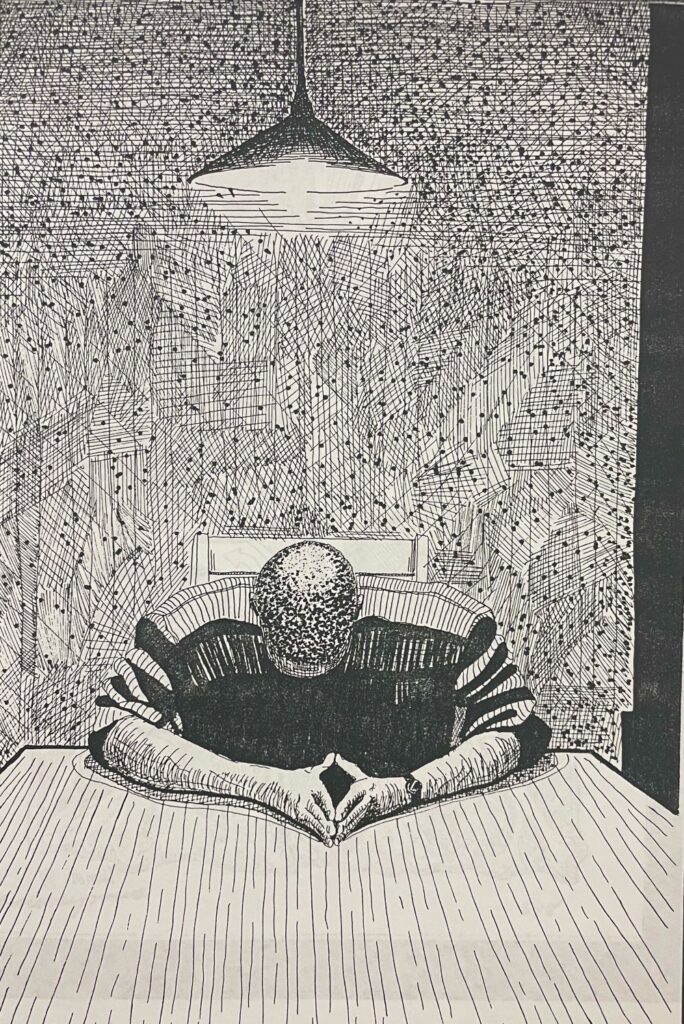

In a large, sunlit room in Los Angeles, I wait for the meeting to start. Volunteers pull aside a room divider and haphazardly set chairs in rows facing a plastic folding table. Some people sit with friends and crack jokes. Others struggle to handle their fussy children. Some sit solemnly, appearing worn down.

Criminals and Gangmembers Anonymous (CGA) is the most well-attended rehabilitation group at the Beacon Foundation, a gang-intervention and (re)entry nonprofit organization. [1] [1] I use parentheses for the prefix in “(re)entry” to reflect the view held by a growing number of criminal justice activists, advocates, and academics that many current and formerly incarcerated individuals have never experienced full membership in U.S. society. I am attending this meeting as part of my anthropological fieldwork with formerly incarcerated people, who often turn to such groups for support both during incarceration and after their release.

O.G. Vee is leading the meeting today. [2] [2] All names have been changed to protect people’s privacy. He has been participating in the Beacon’s (re)entry program after a 14-year stint in prison. Covered in tattoos and standing squarely, wearing a stoic expression, he corrals the group to be quiet.

A handout that describes each of the 12 Steps to Recovery is passed around to participants. Today’s meeting is based on Step 5: Admitting Wrongs to Self, God, and Someone Trusted. O.G. Vee first offers his own experiences and then invites others in the audience to do the same.

“All my life, I’ve been a liar, a manipulator—the worst of the worst,” says one man.

A woman reflects on the experience of losing her children to the Department of Children and Family Services when she was locked up. She feels this loss is what drove her back to an old romantic partner after she was released from prison. They had used drugs together in the past, and she quickly relapsed. She admits to the group, “Guilt and shame kept me there [with him, using drugs].”

Later a different man comments, “CGA is not about gang members, it’s about criminal thinking. It’s still in us, but it’s dormant.”

Throughout my research, I observed how many formerly incarcerated people struggle to cope with feelings of guilt and shame. These feelings are related to deep-seated cultural beliefs about criminality and rehabilitation perpetuated by the U.S. carceral system, which often provoke a moral struggle of what it means to be a “good” person after incarceration.

The stories of those who have experienced this fraught process shed light on both the benefits and limitations of programs like CGA.

TRACING THE FOUNDATIONS OF CGA

Criminals and Gangmembers Anonymous is a 12-step recovery program established in the 1990s that has since proliferated throughout California’s prisons and (re)entry organizations. Gang intervention programs exist elsewhere in the U.S., but the prevalence of CGA within California’s penal system is unique.

Each CGA meeting begins in the same way. Volunteers read aloud from a handout that provides answers to three rhetorical questions:

Who is a criminal? What is a gang? What is the lifestyle addiction?

CGA is explicitly modeled on Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) in its self-help organization, pedagogy, and rehabilitative philosophy; it contends that spiritual transformation, broadly defined, is the path to controlling the “criminal lifestyle addiction.” In other words, CGA maintains that criminal behavior is akin to a chronic addiction, similar to that of drugs and alcohol—but that people are capable of change. [3] [3] The CGA Facilitator Training Manual, for people who facilitate group meetings, describes the lifestyle addiction as “the most vicious and powerful of destructive forces.” Like AA, the CGA program understands addiction to criminality as a disease: chronic, progressive, and rooted in compulsion.

These principles have a long history. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, ideas about rehabilitation in the U.S. penal system largely came from a Christian humanitarian morality and reformist philosophies of Enlightenment thinkers. These perspectives argued it was the state’s responsibility to rehabilitate people charged with crimes and reintegrate them into society.

But in the second half of the 20th century, the U.S. shifted to a markedly more punitive approach. For example, then-President Richard Nixon declared a “war on drugs” in 1971 that disproportionately criminalized Black and Brown people. In the 1980s, legislators under then-President Ronald Reagan made severe cuts to social welfare programs. Policymakers and academics alike also increasingly began leveraging psychological theories that blamed crime on individual psychological problems rather than social and environmental circumstances.

In California, the government constructed 23 new prisons between 1982 and 2000. Today its criminal legal system is one of the largest in the country, second only to Texas. A shocking 458,000 people are incarcerated in state prisons and municipal jails or are on parole or probation. Black and Latinx individuals are disproportionately incarcerated; they constitute 72 percent of the prison population in the state despite representing only 45 percent of the general population.

Although religious ideologies no longer officially inform the U.S. penal model, religious influence has not disappeared altogether. In the early 2000s, federal legislators slashed funding for nonreligious programming in prisons, while then-President George W. Bush allocated funds for faith-based initiatives to deliver social services to communities. This led to a resurgence of faith-based rehabilitation groups in prisons, and they remain some of the most accessible programs today.

Today psychological therapy programs and religious initiatives operate alongside one another. Faith-based rehabilitation groups like CGA identify “warped beliefs” and “defects of character” as characteristics that individuals should work to change, similar to cognitive behavioral therapies that emphasize unlearning maladaptive thinking patterns.

Consequently, CGA often echoes the individualistic conception of criminality rather than considering how systemic inequalities, among other factors, contribute to mass incarceration. I found it was this individualistic view that commonly lay at the root of people’s struggle with guilt.

The following stories of Mariana and Chalo, both formerly incarcerated, show how people navigate guilt when encountering rehabilitation groups like CGA.

MARIANA: FINDING HOPE THROUGH GOD

Despite growing up in a Catholic family, Mariana always felt out of place at church. In an interview, she shared that her mother and father fought constantly, and her extended family were always “selling drugs or drinking or partying or gangbanging.” By the age of 13, Mariana’s parents had lost their family home, and they were living out of a trailer. Soon she was caught up in gang life, drug addiction, and a seemingly never-ending cycle of stints in juvenile hall.

To Mariana, juvie felt like a second home. “You have real gang member girls, or you have girls that are just on drugs and they’re running away from their parents, or being pimped out, or whatever it is. You kind of click in where you fit in with your people,” she told me.

At 16 years old, Mariana was facing the possibility of “juvenile life,” an indeterminate sentence for minors eligible for parole review after a set number of years. She had also given birth to twins, one who passed away just a few hours after birth and another who required serious medical attention.

“I didn’t feel I deserved anything,” Mariana said.

Mariana was given a lighter sentence because she was a new mother. But this mattered little to her; she was already overcome with guilt and struggling with depression. “I didn’t know how to cope with all that,” she said. “I was very young and very confused and very broken.”

She added, “I didn’t deserve to be out. I [didn’t] deserve to be a mother to my daughter because of the choices that I made. I didn’t feel I deserved anything.”

Finally, after getting out of prison at the age of 19, Mariana found the Beacon Foundation. There she attended therapy sessions and rehabilitation groups such as AA and CGA. Through these groups and a local church that served gang members, or “the people that [other churches] don’t want,” as she phrased it, her faith was renewed.

Mariana finally felt a sense of hope, belonging, and value. This community understood her—they were like her. Now she feels grateful: “God protected me from so many times that I could have gotten really, really hurt or so many times that something really, really bad could have happened to me.”

CHALO: HEALING THROUGH HISTORY

While Mariana embraced the model of rehabilitation offered by CGA, Chalo took a different perspective: He worked to reconcile guilt by establishing a new relationship with his past.

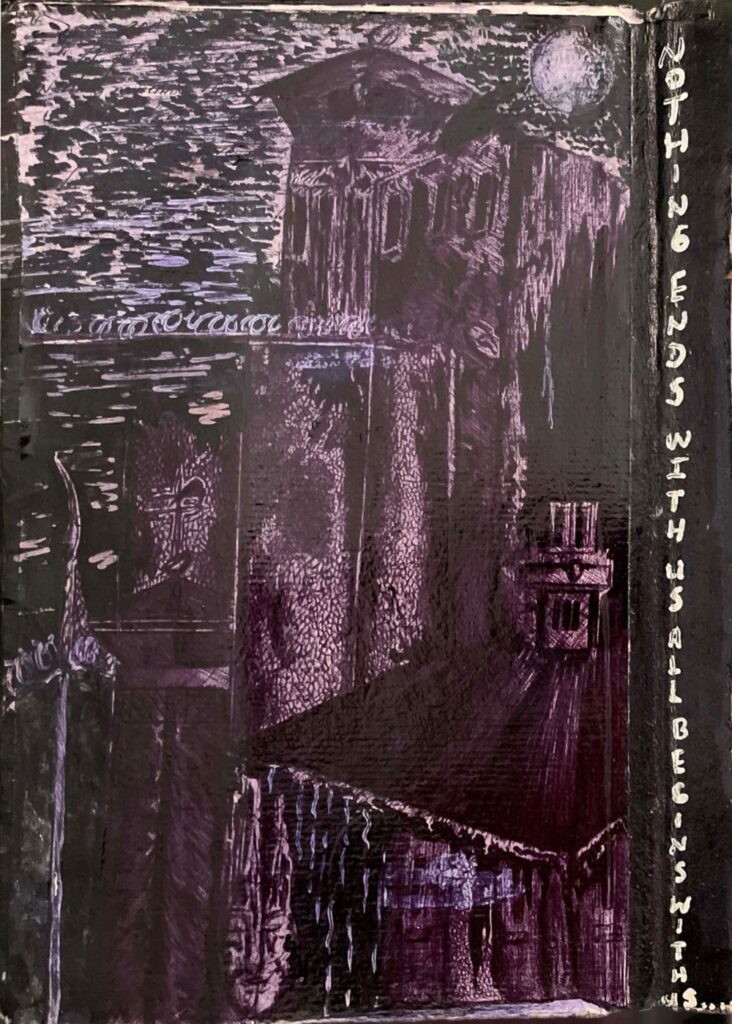

Chalo’s mother immigrated to the U.S. when he was an infant, leaving him in El Salvador with relatives during the Civil War, which exposed him to extreme violence. At one point, guerilla fighters even occupied his uncle’s home. Those experiences seemed to prime him for gang life. As he told me in an interview, “It was like college for who I was to become after.”

By age 14, Chalo had joined his mother in Los Angeles. She had remarried, and when his new stepfather drank, he became abusive. Chalo promptly ran away from home and soon joined a gang. “I didn’t care about anything because I felt that my elders didn’t care,” he said.

Feeling numbed to violence and emotionally disconnected, it was not long before Chalo was arrested and in county jail facing an indeterminate life sentence, charged as a juvenile. “That’s when I really wanted to commit suicide,” he remembered. “I went from being a full-blown gangbanger to the shame that I brought my family, my guilt.” The next almost 24 years of incarceration offered little relief from violence.

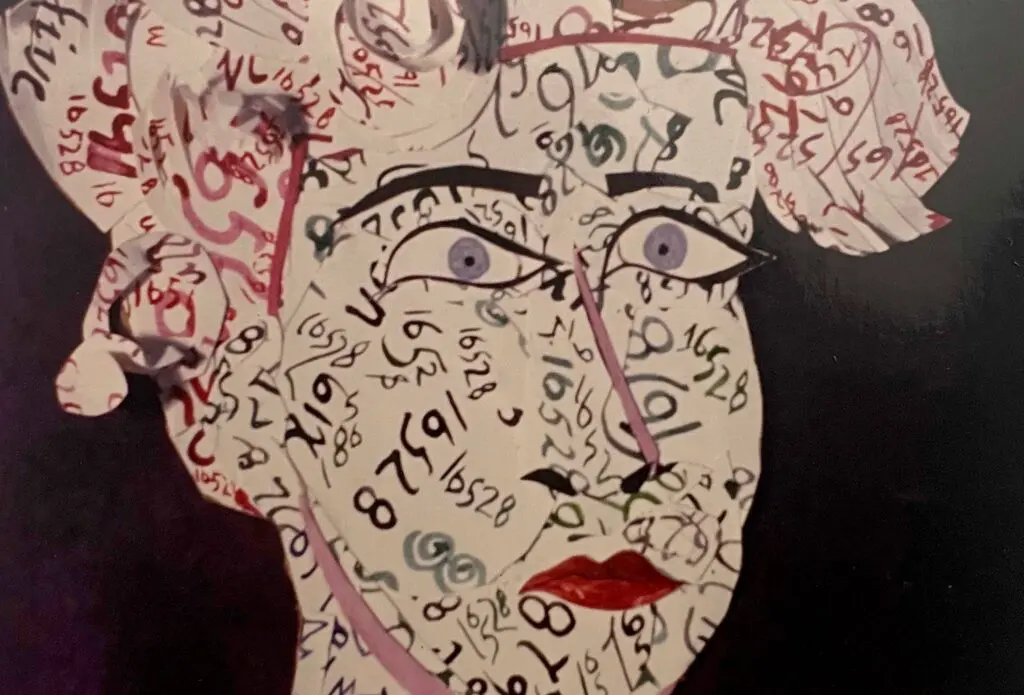

These memories and feelings weighed heavily on Chalo. One day he talked about this guilt in a way I had not heard before. “It don’t mean when the courts say you’re guilty, because I’m guilty of way more than that,” he said. “I’m guilty of being a human being, of my circumstances … of having been born in a country that was very violent. In other words, I embrace my guilt.”

Although CGA initially provided Chalo with a community, he resists the individualistic conception of criminality espoused by rehabilitation narratives. And while he considers himself a spiritual person, he rejects organized religion and its moral “scripts.” In Chalo’s view, these narratives portray people like him as “broken things.”

Instead, he works to contextualize his guilt within social relationships and broader circumstances. It is this perspective that motivates him to move forward in life.

MOVING PAST GUILT

For Mariana, finding community through shared experience is what allowed her to reconcile guilt through her faith.

Chalo now works for the Beacon Foundation and spends much of his time counseling new members. Once, when someone had gone missing, Chalo spent the entire day looking for him, wondering if something terrible had happened.

“I do get worried,” he said. “That’s actually a good thing. It means that I retain some of my humanity, that I care about him. Because inside [prison], I couldn’t show that I care about [anyone].”

Mariana and Chalo are far from alone in grappling with moral questions. And the consequences of internalized shame can be severe: Despite decades of calls for reform, California’s prisons have long had a higher rate of suicide than the national average for state and federal prisons in the U.S.

By blaming crime solely on individuals, prison and rehabilitation discourses often contribute to this deep sense of guilt in people.

There are, however, movements that challenge this perspective. Scholars have identified the complex interplay between politics, capitalism, and social inequality as the foundational impetus for mass incarceration. This is why abolitionists call for widespread systemic change—to envision and build a healthy, equitable society without any need for prisons.