Unmasked: Illustrating COVID-19 in Okoboji

These illustrations tell the story of the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in a small tourist town in the Iowa Great Lakes region: my hometown of Okoboji.

At first, during the first several months of the pandemic, most people in the largely White, Christian, and conservative community stayed home and agreed “we are all in this together.” However, by May 2020, when the sun came out and the nearby lakes warmed up, the collective commitment to public health turned to the economy. In Okoboji, many people rely on tourist income from the 100 days of summer to stretch over the year, and losing that income was inconceivable.

Although originally from Okoboji, I am now a medical anthropologist and professor at Georgetown University. Having spent two decades investigating how people perceive and experience illness across contexts, confronting my hometown’s response to the pandemic was fascinating. I arrived in the middle of an outbreak in early June 2020, after having spent time in strict lockdown on the East Coast. I quickly realized that nearly everyone was unmasked and that there was something fundamentally different going on when compared to the locked down city of Washington, D.C., where I’d come from.

But this shouldn’t have been too surprising—Iowa was one of a handful of states that did not enact a formal “stay-at-home” order. Republican Gov. Kim Reynolds closed schools, churches, restaurants, and many retailers for a few weeks in 2020, then quickly reopened, despite warnings from public health officials. Many nonessential offices have stayed open during the pandemic thus far.

My account of this period was published as Unmasked: COVID, Community, and the Case of Okoboji. The new book draws on 86 formal interviews, 13 public testimonials, transcripts from school board meetings, observations of behavior and everyday talk, and countless Facebook exchanges. In Okoboji, I talked with business owners and elected officials; people who worked in the hospital and for schools, nonprofits, and health centers; and some who held multiple jobs or shift work at large national or regional stores, restaurants, cafés, gift shops, grocers, or manufacturing plants.

Many people told me, “I don’t fear the virus because I believe in God”—wielding a deeply religious and somewhat magical way of thinking about the virus. Others rejected public health recommendations because of political beliefs as opposed to religious ones, such as a conviction that government overreach was out of hand. A handful of people openly suggested they wished to spread the virus to build immunity across the community. Yet most people took great care in preventing COVID-19 transmission in 2020, especially among loved ones and the most vulnerable in their lives.

Recently, I collaborated with Aaron Gronstal, an astrobiologist and visual artist also from Okoboji, to create a series of comics based on this research. Aaron, who now splits his time between Scotland and Okoboji, also felt the collective shifts of the first pandemic summer. He was interested in working together to find a comic illustration style that could help translate Unmasked into visual form. Aaron designed, drew, colored, and edited each full-page piece to help tell the complicated story of COVID-19 in Okoboji.

—Emily Mendenhall

Families Transformed

For many working families in Okoboji, COVID-19 transformed how they cared for their children. This pressure was particularly difficult for parents—and especially mothers—working in restaurants and manufacturing plants, such as Cheri [1] [1] All names of interviewees have been changed to protect people’s privacy. . As I recount in Unmasked: “When we spoke in July, Cheri was exhausted after months of struggling financially and caring for her four children. ‘Our year started out pretty normal,’ she said. ‘But then they let school out, so I ended up quitting my job because I had to stay home with the kids. And day care closed. And nobody wanted to watch anybody’s kids because they were afraid they were gonna get sick.’” This first comic illustrates Cheri’s perspective—one many women in Okoboji shared with me during the early days of the pandemic.

Opening Up

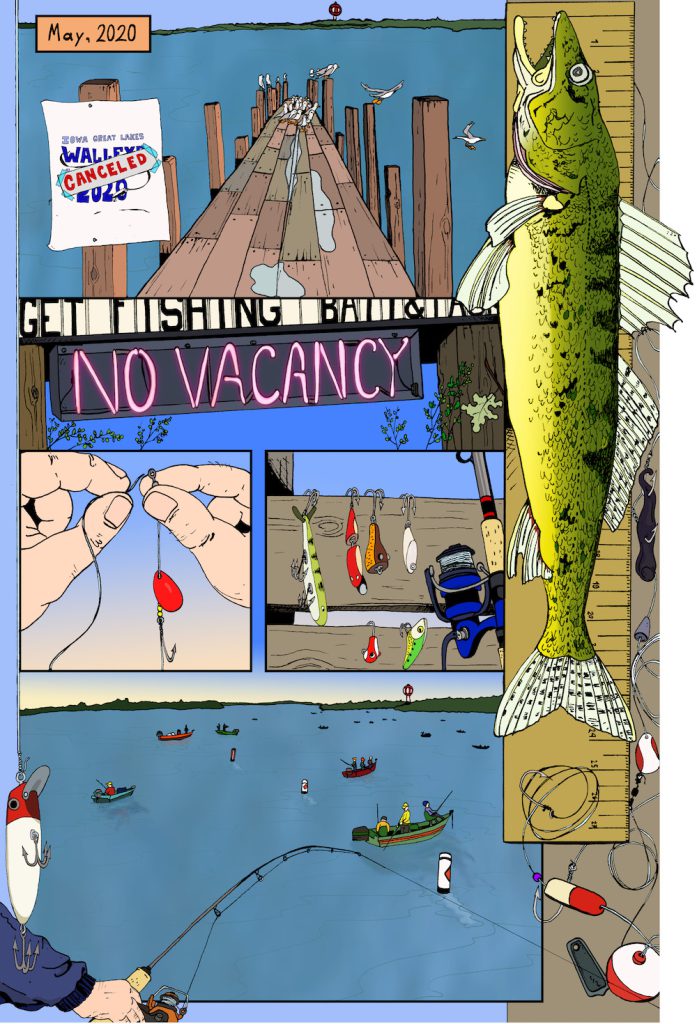

Many people descend on Okoboji during the first weekend of May for “Walleye Weekend”—a fishing competition and the unofficial “opening up” for the tourist season. Although the competition was reorganized and delayed in 2020, the hotels filled up. Local business owners and politicians started pushing for the summer tourist season to continue as usual, despite some ongoing concerns over the pandemic.

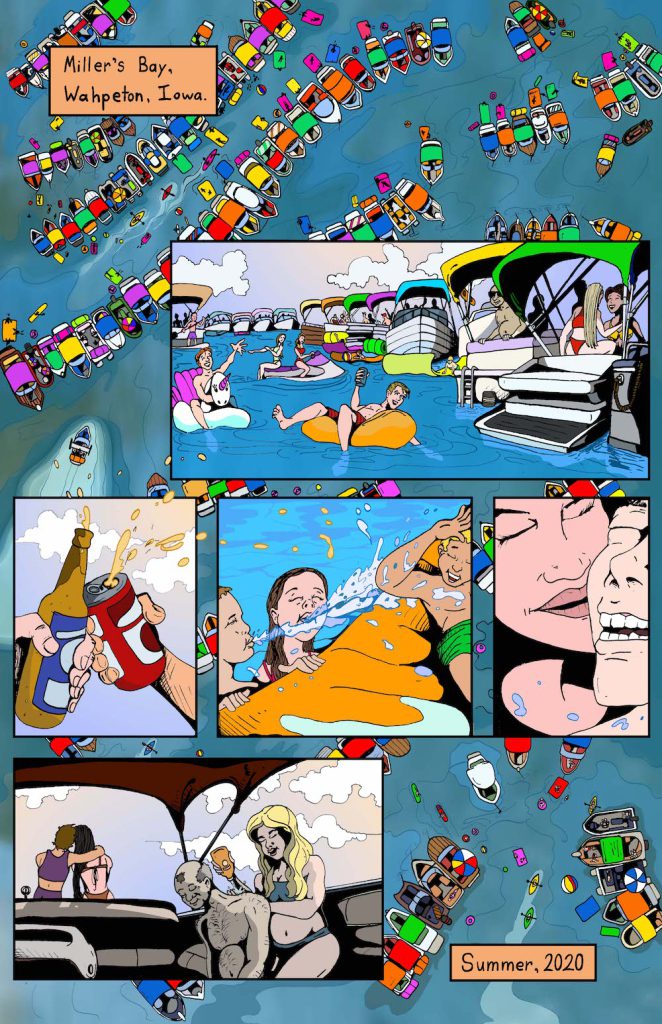

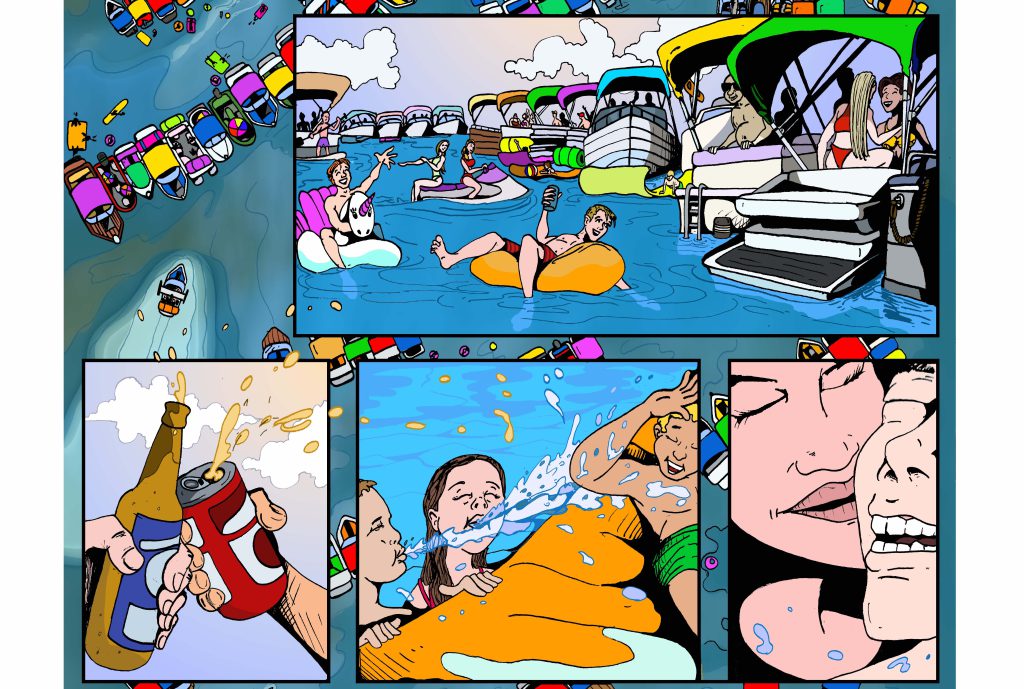

COVID BAY

Party culture is at the heart of an Okoboji summer. On Tuesdays, many restaurants and bars around town are closed, so employees gather and party on boats in a part of the lake known as Millers Bay. By June of 2020, rumors spread that SARS-CoV-2 was being transmitted at these parties, and people renamed the spot “COVID Bay.” In Unmasked, I recount a conversation with an interviewee who explained how these conditions led to the spread of the virus over the summer: “I realized that the spike in cases happened among young people who cooked the food, served the drinks, and cleaned the tables at some restaurants and then would canoodle with those who worked at other restaurants around town.”

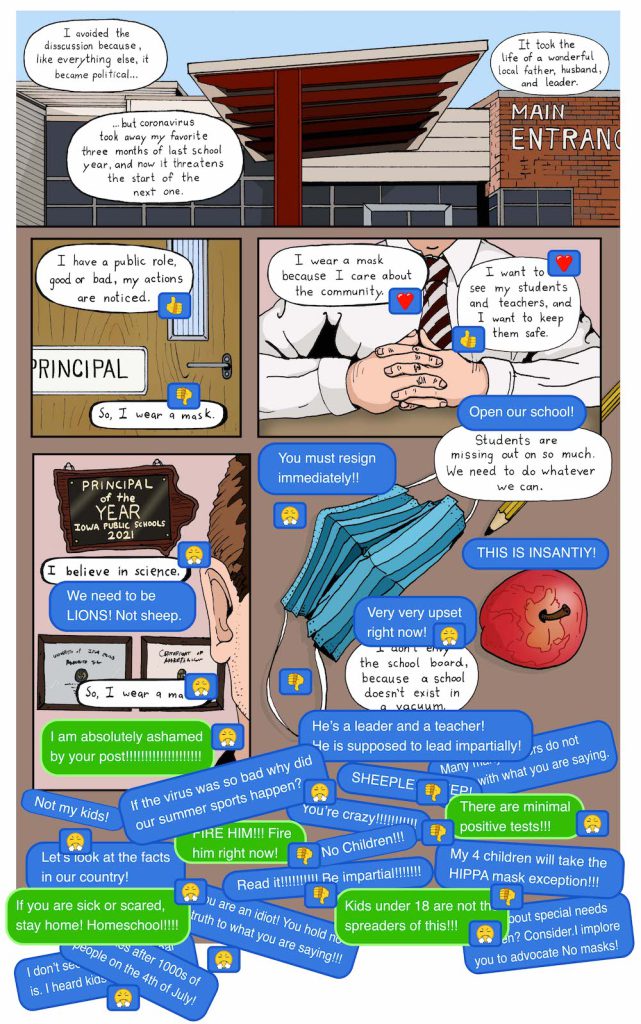

Masking in Schools

In July of 2020, Gov. Reynolds mandated public schools reopen, with students expected to be in-person for at least half their schooling. Without any policy guidance about public health regulations, local debates over masking became heated. One high school principal who posted to his personal Facebook page about why he chose to wear a mask in support of public health received a shocking amount of backlash from parents. Some parents threatened to withdraw their children and home-school them.

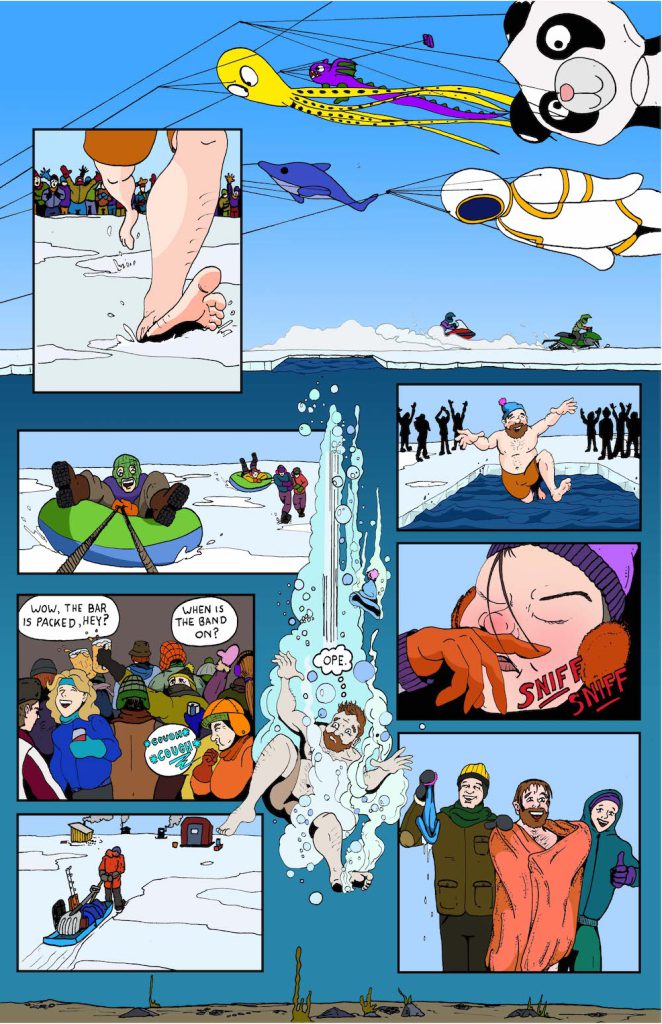

Winter Games

The county briefly instated a mask mandate during a major surge of cases in fall 2020, with many hospitalizations and deaths in the region. But after Christmas, a big winter festival in Okoboji called the “Winter Games” was held as usual, signaling that the community was moving on. Some modifications were made to reduce the virus’ spread, although many indoor unmasked gatherings occurred.

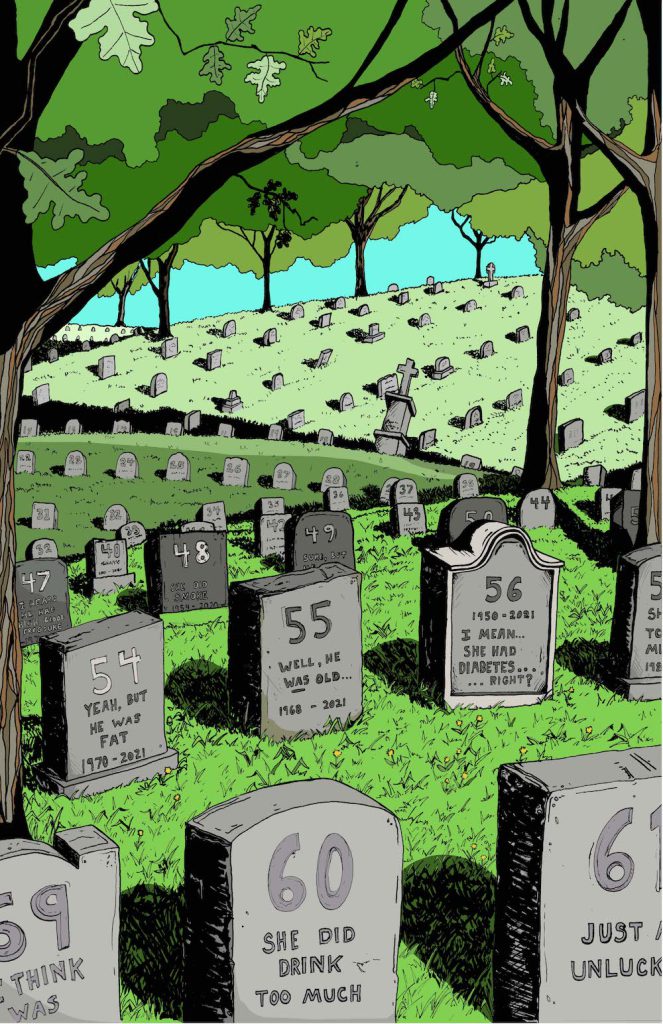

Memorialization

In mid-June I heard, “Nobody will take [the virus] seriously until someone prominent in the community dies.” However, a couple weeks later a well-known member of the community died from COVID-19. Many others followed, including a 59-year-old local officer for the Department for Natural Resources. However, most people explained their deaths as the result of being older, overweight, having preexisting conditions, or engaging in behaviors like drinking and smoking. Many people repeated that those who were vulnerable should stay home.

Life improved for many people once vaccines arrived. By May 18, 2021, 80 percent of residents over 65 years of age were fully vaccinated, as were 55 percent of those between 18 and 64. Many families who had been exceedingly careful throughout the pandemic began to resume their pre-pandemic lives. Nearly every formal COVID-19–related policy had been removed by May, and many in the town felt the pandemic was over.

Still, cases of COVID-19 continue to ebb and flow in Okoboji today. As of May 2, 2022, 72 people have died in a community of 17,000 year-round residents.