Gold Glimmers in the Amazon

Early in the morning, when the sky is still dark, the men rise from their hammocks. These gold miners of Amazonia slip on their flip-flops and walk toward the light, sometimes stumbling on roots and other remnants of the forest. At the kitchen, they pour sweet steaming coffee into old jam jars, gripping the hot glass with their fingertips. They shake off the chill, stretch away the aches, and follow the steady purr of the excavator to the open-pit gold mines.

When European adventurers and explorers arrived in the Americas, they were intoxicated by tales of Native people’s gold, and ventured deeper and deeper into the jungle in search of the legendary land of riches known as El Dorado. The allure of gold has persisted through the centuries, and today thousands of miners (garimpeiros in Portuguese) from all walks of life scour the Amazon rainforest in search of riches, or at least a future that is a little brighter.

In 1979, a boy found a gold nugget in a stream near a mountain called Serra Pelada (Naked Mountain) in the Brazilian state of Pará. The news spread, thousands of miners arrived, and soon the mountain was reduced to a gigantic crater. Photographer Sebastião Salgado’s dramatic images, taken in 1986, conveyed the misery of Serra Pelada to the world, and he later described the scene as “an extraordinary and tormented view of the human animal: 50,000 men sculpted by mud and dreams. All that can be heard are murmurs and silent shouts, the scrape of shovels driven by human hands, not a hint of a machine. It is the sound of gold echoing through the soul of its pursuers.”

Serra Pelada was one of the biggest gold strikes in history, but it was only one chapter in the Amazonian gold rush of the 1970s and 1980s. In the 1990s, gold prices crashed. In the mid-2000s, many areas containing gold deposits were made off-limits as protected forests or national parks, and small-scale mining seemed to be coming to an end. In recent years, however—with international gold prices fluctuating between about US$1,200 and US$1,800 an ounce—the illegal gold fields of Amazonia have been surging with activity again, this time aided by powerful new technologies.

The scrape of shovels Salgado described has been replaced by the steady plodding of hydraulic excavators that run night and day. A single excavator, with its powerful shovel, can clear a patch of forest and dig a pit 30 feet wide, 90 feet long, and 30 feet deep in a few days—a task that would have taken months by hand. The machine makes it easier to reach gold deposits that were too deep or sparse to warrant the effort before. The profits are potentially higher, but so are the operating costs, and the impacts on the Amazon environment have increased substantially.

A 2015 study reports that between 2000 and 2013, approximately 1,680 square kilometers of tropical forest were destroyed for gold mining at roughly 1,600 mining sites studied in South America. Mercury and cyanide, which are widely used for processing and extracting gold, contaminate waterways, fish and wildlife, and the people who rely on these resources. The miners themselves suffer from health issues related to working directly with toxins.

International reports with jarring headlines present the environmental destruction as part and parcel of a ravenous and immoral industry: “Miners’ Attack on Yanomami Amazon Tribe ‘Kills Dozens’” and “Gold-mining in Peru: Forests Razed, Millions Lost, Virgins Auctioned.” In a 2015 CNN story, “Inside Brazil’s Battle to Protect the Amazon,” a raid by armed environmental authorities ends with miners shackled on the ground, watching as their equipment and belongings are torched.

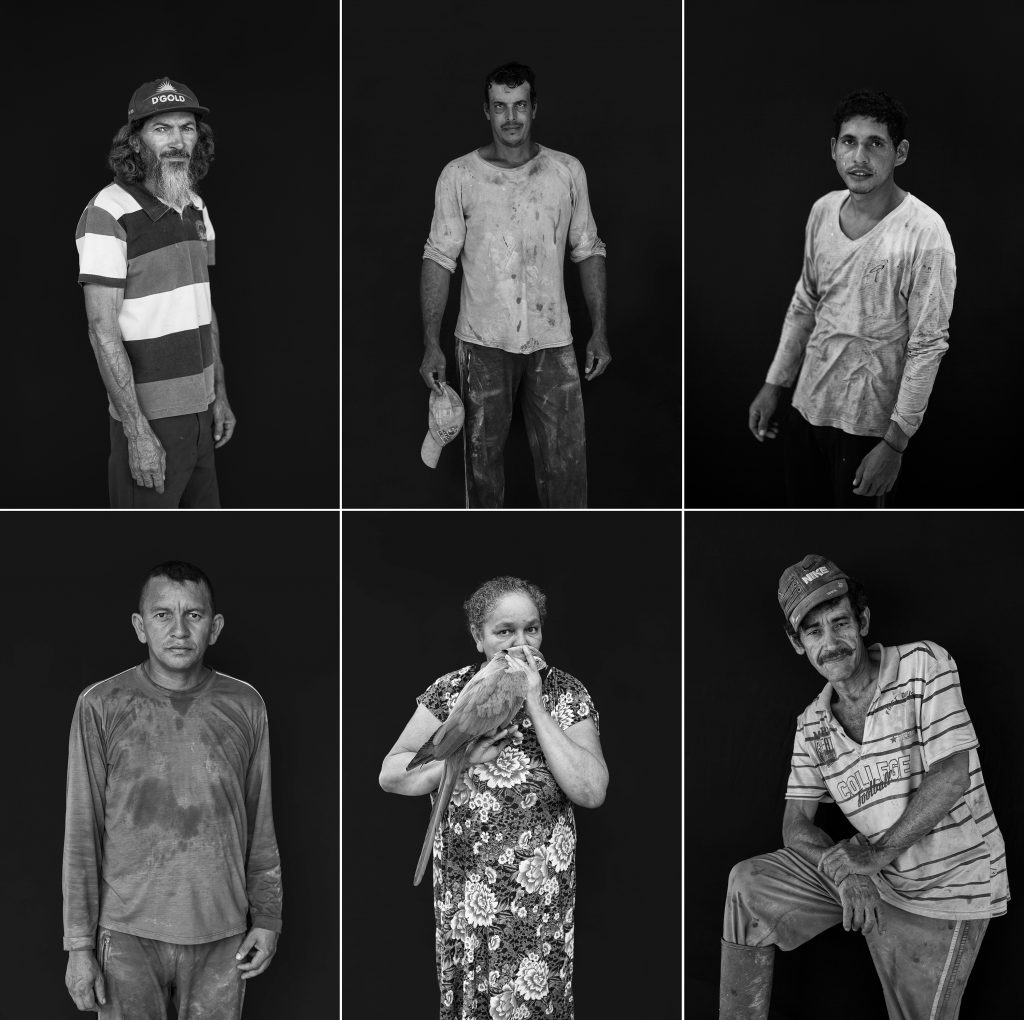

These quick glimpses into a rough world are certainly shocking, but they tell us little about daily life in the gold mines of Amazonia. What is it like in these illegal gold camps? Who are the miners and what draws them here? How do they coax gold from the ground in this new age of excavators and governmental surveillance?

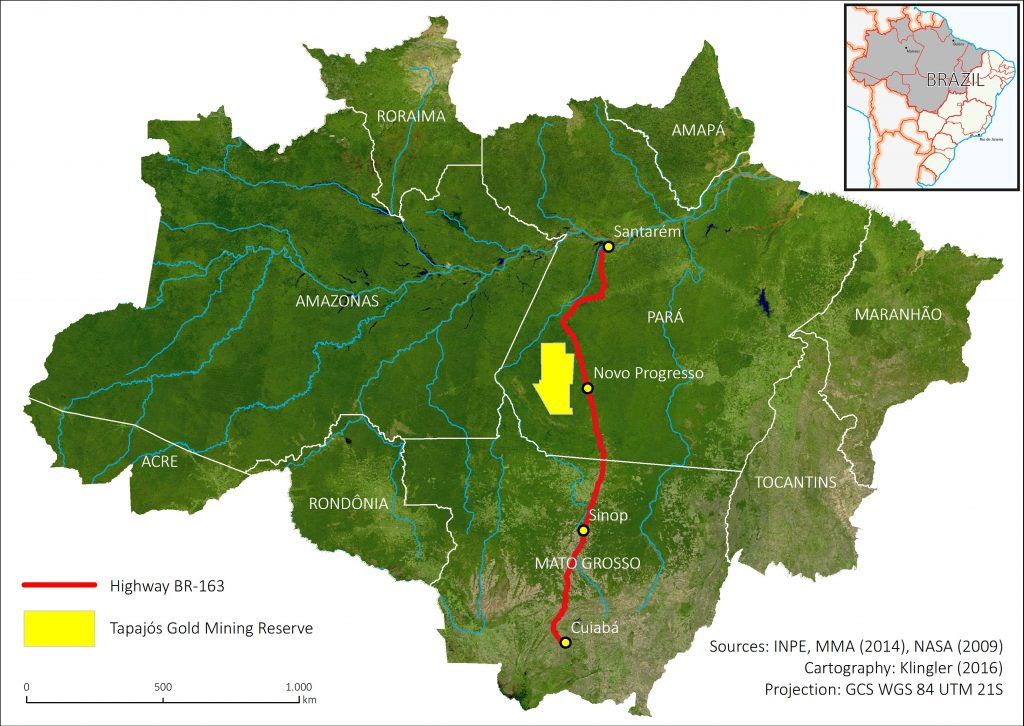

In 2014 and 2015, our team—comprised of an anthropologist, an economist, and a geographer—visited the gold camps of the Tapajós River basin in the Brazilian Amazon with the aim of answering these questions and providing a more complete picture of the gold mines (garimpos) and the miners working and living in them. [1] [1] This research was supported by a grant from the National Geographic Society.

From the town of Novo Progresso, Pará, we followed the BR-163 highway north and then tracked along the dirt back roads and paths in search of the camps. We flew just above the treetops in Cessnas that had no seats before abruptly touching down on airstrips carved out of the forest. Experienced miners showed us the way and helped ease some of the suspicion that people in the camps felt toward outsiders.

In some camps, we stopped for a few hours to talk under the shade of black plastic tarps draped on rough-hewn timber posts, and we took pictures of the mines and miners. [2] [2] All names in the following photo essay are either nicknames or pseudonyms to protect people’s identities. In other camps, we were invited to tie up our hammocks inches away from the miners and experience the process of extracting gold—from the excavator’s relentless clawing at the earth to the blasting of bedrock with a high-powered hose, and finally to the moment of truth, when the find was weighed and divided. After work was done, we ate dinner at long wooden tables and listened to incredible stories of riches and despair. We accompanied the miners on their trips into town, where they sold their finds and celebrated.

Despite increased enforcement and negative press, the miners rely on the fact that the environmental authorities are short-handed and only motivated to make a bust if Indigenous or protected areas are encroached upon. Even then, the miners know how to elude detection by making small clearings, and when a raid is coming, the news spreads quickly over the radio, providing them with time to hide or abandon their camps. Some of the miners we met had worked in camps that were raided and burned, but here they were, back at the mines.

The people we got to know came for the gold, and what it promised. They were, at least at the beginning, united by a hope that their struggles deep in the unfamiliar forest and far from their families would lead to a better life—one otherwise beyond their reach as unskilled laborers in Brazil’s growing cities.

Seasoned miners said it was easy to lose track of time while living at the mines. The search for gold was a slippery, vengeful cycle of jubilant discovery and celebration followed by an urgent need to get more or recoup what had been lost. With each cycle, the hole becomes deeper. They clung to the hope of the mother lode while their bodies deteriorated and the ties that bound them to the people and places they once called home dissolved.

We saw the despair and destruction, but we also saw powerful bonds formed among miners and observed the tender care they gave to the injured and vulnerable among them. In a place that people told us was violent and lawless, we came to know the strict code of conduct in the ragtag camps and the discipline and ingenuity that went into creating those haunting, otherworldly craters and raw gashes in the forest.

The mines can be photographed in such a way that the images conform to expectations of misery and degradation, but here we train the lens on scenes that facilitate a more complex rendering of the mines and the real people doing the hard living in the gold fields of Amazonia.

All videos courtesy of the authors.