Interplanetary Environmentalism (Part 1)

On Earth we sometimes identify and protect places we recognize as holding special cultural, scientific, religious, political, historical, or heritage value. By doing so, we hope to preserve something greater than the material resources which might be extracted from the land. We hope to protect biodiversity, archaeological records, sites of historical events, or just the beauty of a unique landscape.

Anthropologist Valerie Olson has found in her research that the limit of what we consider to be part of our natural environment is now expanding out into the solar system—into what she calls an “environmental solar system.” If there’s value in preservation and conservation of the environment here on Earth, what about in space, on Mars, and on other worlds? Should landscapes and spacescapes beyond Earth be protected as well?

Since landing in Gale Crater in 2012, NASA’s robotic rover Curiosity has explored, photographed, sampled, analyzed, and even drilled the surface of Mars. Pondering a photo of drilling results, the tiny drill hole (1.6 cm) in the photograph struck me as a distinctly human signature on the Martian surface. However small, these drill holes on Mars are a reminder of possible future human impact on the landscapes of other worlds in our solar system.

Article IX of the U.N.’s Outer Space Treaty says that in the course of exploration and use of outer space, parties to the treaty must avoid harmful contamination of the moon and other celestial bodies. Planetary protection specialists work to ensure that when we send spacecraft to other worlds, we avoid biological contamination in both directions. NASA’s Office of Planetary Protection aims to “preserve our ability to study other worlds as they exist in their natural states.” But where is the line between a natural landscape and an unnatural one? How much impact on another landscape is too much? And at what point would human activity on Mars disturb the “natural state” of the planet?

We have sent spacecraft to planets throughout our solar system. Some have landed and others have crashed. These spacecraft, the places they explore, the crash sites, and the stories we tell about them are all part of our cultural heritage, and as space archaeologist Alice Gorman points out, they make up a broader cultural landscape of space. They also represent our impact on the landscapes of other worlds, which, until recently, have been entirely free of our influence. For billions of years—until 1971, when Mars 2 crash-landed—the surface of Mars was free of anything created by the primates of Earth. Now, at least 13 human-made objects have landed on or impacted the surface of Mars.

In a panel discussion at the SETI Institute about when we might find life beyond Earth, Nathalie Cabrol, director of the Carl Sagan Center, talked about the possibility that Martian landscapes could preserve a record of the emergence of life. Mars, Cabrol explained, has not been subjected to the violent surface rearranging that has been happening on Earth since life first emerged here. The record on Earth beyond 4 billion years ago has been erased by plate tectonics and erosion. All evidence of the time on Earth when prebiotic chemistry became life may be gone. This is not the case on Mars, Cabrol says. If life on Earth was seeded by comets or asteroids, the same thing could have happened on Mars. Or, perhaps material ejected from Mars sent life to Earth. If there was ever life on Mars, the fossil record of the time when it emerged may still be accessible. Such fossil records would be another kind of cultural heritage, providing us with new scientific stories about the emergence of life in our solar system.

There may also still be life on Mars today, underground or elsewhere. At the SETI Institute panel, Margaret Race, who works on planetary protection, asked, “If we find life there, does that mean that Mars belongs to Martians?”

And even if we only find evidence of life from the distant past, I wonder if we will protect that scientific and cultural resource on Mars.

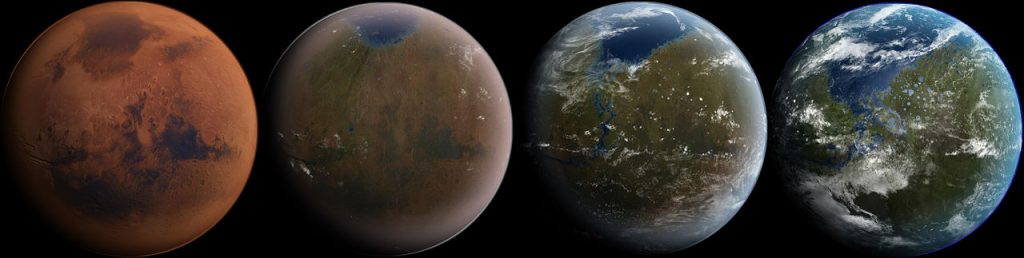

SpaceX CEO Elon Musk recently announced his plans to send an uncrewed spacecraft by 2018 to land on Mars and return to Earth. Musk says he intends to build human settlements on Mars, and, along with organizations like the Mars Society, he has talked about terraforming the planet (making it more Earth-like). The careers section of the SpaceX website even depicts Mars transforming over time from the Red Planet into a blue-green world, like Earth. Is this the long-term work SpaceX hopes to do on Mars? What place would preservation of Martian landscapes, ecosystems, and the cultural heritage of landing and exploration sites on Mars have in these plans, if any?

Terraforming Mars would mean fundamentally changing the planet. In a video about possible visions of colonizing Mars, Mars Society founder Robert Zubrin invokes Christopher Columbus and the colonization of western North America. This narrative is common in space exploration—especially in the private space industry, where libertarian and capitalist values often dominate discussions, and space is seen as a new frontier waiting to be settled.

In the same video, planetary scientist Margarita Marinova, formerly at NASA Ames Research Center and now at SpaceX, explains that one way to terraform Mars would be to create global warming there using greenhouse gasses through anthropogenic (human-caused) climate change. To terraform Mars, in other words, humans might intentionally cause the same planetary crisis on Mars that we are facing here on Earth. The Anthropocene might not only mark the beginning of the era of planetary-scale human impact on Earth, but also the time in our history when we begin to permanently alter other worlds.

Is a cold and possibly lifeless world like Mars worth protecting from human-induced changes? Perhaps this solar system is ours to do with as we want—a collection of planets waiting for human colonization. But what if Earth is not the only planet in our solar system with indigenous life? In Part 2 of this post, I’ll consider whether we have a responsibility to protect our neighboring worlds as we reach out to settle and explore.

Read Part 2.