Our Living Message for Extraterrestrials

On March 23, 2016, Microsoft brought a new artificial intelligence (AI) online. Named Tay, she was linked to social media accounts on Twitter, Facebook, and other sites so that she could interact with users and learn how to have conversations with humans. However, Tay soon started to agree with racist and white supremacist posts from social media users and went so far as to deny the Nazi Holocaust, tweet “feminism is cancer,” and make transphobic statements. The image of ourselves she reflected was so disturbing that Microsoft shut her down after less than a day online. As The Telegraph headline put it, “Microsoft deletes ‘teen girl’ AI after it became a Hitler-loving sex robot within 24 hours.”

Setting aside the nuances of Tay’s programming and other factors in the experiment, this story got me thinking about the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI). How might we communicate with alien life from other worlds? What would we even say if we could?

In an episode of the online radio program StarTalk, host and astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson spoke with Elon Musk, CEO of the private space corporation SpaceX, about the possible threat of a “superintelligent” AI from space. “Aliens,” deGrasse Tyson later wrote, “will make pets of us.” Reactions across social media and in the news ranged from calling the comment a lighthearted joke to taking it as a serious assessment of threats waiting for us in interstellar space. The conversation came at a moment when the SETI Institute, a scientific nonprofit dedicated to understanding the origin and nature of life in the universe, had announced renewed interest in “active SETI”—the practice of transmitting messages in the hope of contacting intelligent extraterrestrial life.

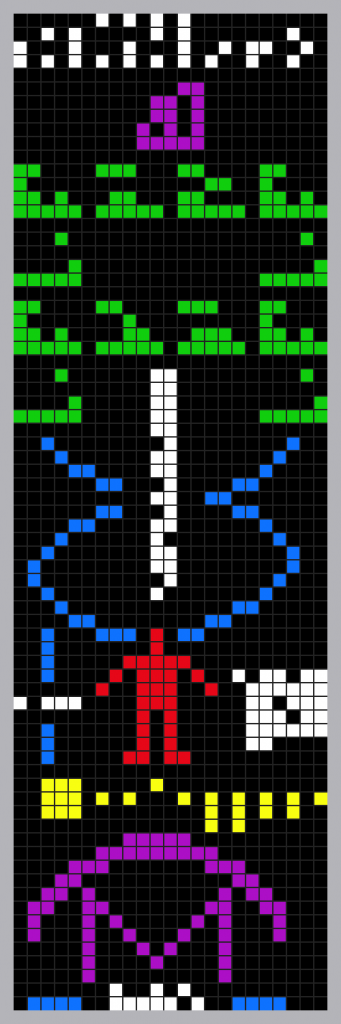

Since the Arecibo broadcast of 1974, over 20 transmissions have been attempted by researchers, the public, and private interests, with the aim of contacting extraterrestrial intelligence. In February 2015 at the annual meeting of the world’s largest scientific association, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), scientists from SETI met to discuss transmitting messages into space. Musk and 27 others responded with a statement on the possible dangers. They used the acronym METI, which stands for “messaging to extraterrestrial intelligence.” They warned of “unknown and potentially enormous implications and consequences.” And they closed by stating: “Intentionally signaling other civilizations in the Milky Way Galaxy raises concerns from all the people of Earth, about both the message and the consequences of contact. A worldwide scientific, political, and humanitarian discussion must occur before any message is sent.” In response, Seth Shostak, senior astronomer and director of the center for SETI research at the SETI Institute, wrote an op-ed in The New York Times arguing in favor of active SETI. “The universe beckons,” Shostak said, “and we can do better than to declare that future generations should endlessly tremble at the sight of the stars.”

Perhaps the Microsoft programmers who created Tay assumed that by interacting with humans online and conducting related internet searches, the artificial intelligence would reflect an idealized image of humanity and how we communicate. Instead Tay showed us the worst of humanity’s prejudice, hatred, and bigotry. Tay is a reminder that we may not have as much control over the messages we do send to extraterrestrial life and that we may, in fact, already be sending a message.

Like Tay interacting with people on Twitter, extraterrestrials won’t only see what we intend them to see. They will see all of us—everything we do and say, our entire planet, the full range of what it is to be human. They will see our bigotry, hatred, cooperation, and care—our wars, love, power struggles, artworks, stories, songs, and bombs. Just as Tay didn’t see only the good in online discussions, we may not be able to send extraterrestrials a message that represents only the best of our traditions, behaviors, actions, and ideas.

As an anthropologist I’ve learned there is a significant difference between what people say they do and what people actually do. It sounds like common sense, but it has important implications for anthropology, communication, and SETI. This is one reason that in anthropology we use a research method called “participant observation”— which is really just a fancy way of saying “hanging out with people and paying attention to what they do.” If I’m going to meet a group of people and I want to understand what they are up to, what their actions mean, and how they see the world , I could simply ask them what they do. But if I want to really understand what they’re actually doing, I have to spend time with them, go along with them in their everyday activities, and listen, watch, and see for myself what they say to each other and how they react when things go differently than expected. An anthropologist has to learn not only what people say they do but also what they really do.

If an extraterrestrial intelligence can understand anything in the specific messages we intentionally send to them, they will probably also be able to understand (or at least perceive) anything else we are doing. Imagine for a moment that we decide to send out a message announcing that we are a peaceful planet with kind intentions and we are interested in cooperation. Looking at Earth, extraterrestrials might see nuclear weapons, fascist governments, surveillance states, racism, intolerance, torture, poverty, hunger, and inequality amid abundance. In other words, they would probably see through our carefully crafted diplomatic lie.

Life elsewhere in the universe may also be profoundly different from life here on Earth. Extraterrestrial intelligence may be almost unrecognizable, with practices, bodies, and forms nothing like our own. After thousands of years of cohabitation and scientific work here on Earth, we have yet to communicate with other intelligent species on our own planet the same way we do with one another. This suggests the challenge of communicating with extraterrestrial life may be at least as great as communicating with other species here on Earth and probably much greater. On the other hand, we may be able to communicate and be understood by simply mutually witnessing one another—by seeing all of their actions and allowing them to see us in return.

By looking out into space one day with telescopes or via spacecraft infinitely more powerful than those we have now, we may be able to watch extraterrestrial beings go about their lives on another world. While we watch them, they may also watch us here on Earth and perhaps also on Mars and other planets in our solar system where we will be living. And by looking at us, they will receive and understand the only message we can send that can be understood and believed: the sum total of all our actions.

In other words, each word I am typing now, every smile you give your neighbor, every television transmission, each walk in the woods, each weapon built, all our internet searches, every injustice committed, every telescope pointed at the sky—the sum total of every human looking up at the stars. This sum total of all our actions may be the message we are already sending to extraterrestrials, a message composed by and reflecting the best and worst of every one of us here on Earth.