Interplanetary Environmentalism (Part 2)

If you missed my previous post, please see Interplanetary Environmentalism (Part 1).

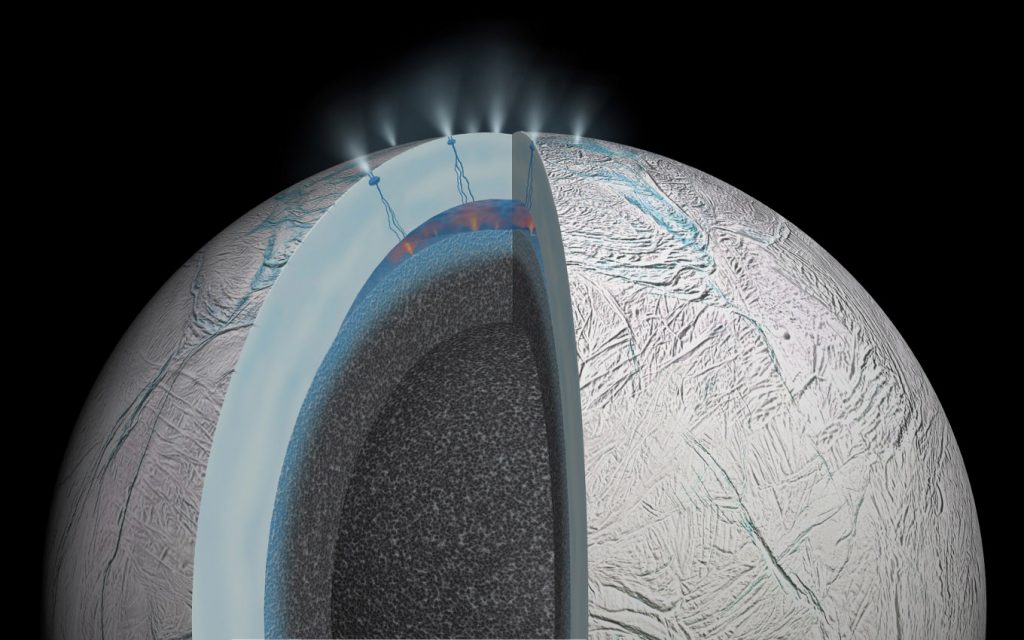

The subsurface oceans of Enceladus, Europa, and other worlds may be home to microbes, similar to those that thrive around deep-sea vents on Earth, or perhaps to other life forms that are not yet known to us. Even if there is only microbial life on other worlds, do we have a responsibility to protect that life as well as its evolutionary potential? Anthropologists Heather Paxson and Stefan Helmreich have found that “human lives are entangled with microbial lives,” all the way from the ocean to fermented foods such as cheese. Just as happened here on Earth, ocean-based life elsewhere could evolve and eventually develop other forms of complexity such as culture, language, and technology. Do we have a responsibility to protect life and landscapes not only as they are, but as they might become someday? Do we have a responsibility to possibilities in the future beyond the scales of living things and time we normally think about?

Humans are only a small fraction of the life on Earth—we make up around 0.05 percent of the biomass of the planet (316 million tons out of over 560 billion). Keeping in mind the diversity of life here on Earth, the possibility of life elsewhere, and the interests of future generations, perhaps we do have an obligation to preserve parts of this solar system and the worlds in it. What would happen if we designated solar system heritage zones and reserves that protect both the landscapes and the possible biological diversity of our solar system?

The creation of solar system heritage zones might be approached in the same way we create national parks, UNESCO World Heritage sites, and biological reserves. Cultures and people across planet Earth place meaning and value in landscapes and in natural spaces—not only for what can be extracted from them, but also for their less tangible values and their future potential. Unfortunately, we have often only recognized this value after irreparable harm has been done, and even then we find our efforts at protecting sites thwarted by human-induced planetary-scale problems.

The idea of planetary parks to protect regions on planets like Mars has been promoted by astrobiologist Gerda Horneck, of Germany’s Institute of Aerospace Medicine, and Charles Cockell, professor of astrobiology at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. Even if land were set aside for planetary parks on Mars, however, these parks and the entire planet would still be irreversibly altered by any attempt at terraforming (making the planet more Earth-like).

If we hope to preserve landscapes and environments on other worlds, the time to do it is now—before those worlds are further impacted by human activity. Hundreds or thousands of years from now, humans may look out over protected landscapes on Mars, study microbial ocean life on the moons of Saturn and Jupiter, look up at the unaltered surface of Earth’s moon at night, and thank their ancestors for protecting these unique worlds. Many of the arguments for settling Mars are about preserving life (particularly human life) in case planetary disaster strikes Earth. But at the moment, the greatest planetary threat to life on Earth is still humankind and our practices. If we hope to preserve human civilization by settling elsewhere in our solar system, we should also ensure that we do not bring with us the same kinds of behavior and attitudes that have put our planet in peril today.

As astrobiologist David Grinspoon writes, “If we go to Mars with the idea that we can charge ahead and subdue a new world, our efforts are doomed. … Mars does not belong to ‘America,’ nor to Earth, nor to human beings.” Colonialism remakes places in the image of the colonizer, erasing existing cultures, landscapes, and natural environments, building empires on top of the ruins, and rewriting history to call that destruction an improvement. Terraforming may not always be a utopian transformation—it could also be a violent imposition of Earthly norms on landscapes elsewhere, a colonization of existing otherworld landscapes which may have a right to remain as they are. Unless we rethink the current colonial approaches to increasingly privatized space exploration, the same history that has led to the problems we face here on Earth may lead us to repeat that short-term thinking and its consequences elsewhere.

When we talk about human expansion into the solar system in terms of manifest destiny, colonialism, and capitalism, we are projecting our shortsighted and violent colonialist ideologies from Earth out into the solar system and into humanity’s future in space. As we work on imagining and creating the technological and survival resources required for human settlements on Mars, we must also innovate to find alternatives to the strategies that have led to inequality, environmental destruction, and climate change here on Earth. Space agencies, scientists, corporations, social scientists, philosophers, and others must come together to discuss how we can pre-emptively decolonize our efforts to settle the moon, Mars, and other places in space.

Yes, humanity must become multiplanetary to ensure long-term survival, and yes, this means living on other worlds. But how we do it matters. Our emerging era of interplanetary exploration demands a new interplanetary environmentalism. The protection of Earth along with our future extraterrestrial planetary homes depends on whether we can find the will to imagine and enact less destructive motives and methods for exploration and settlement.