Watching Ancient Hominins Giving Birth

The movies that Natalie Laudicina makes use the same software that helped create some of the biggest blockbuster hits of the last decade, but her movies won’t be coming to a theater near you. Laudicina, a graduate student in anthropology at Boston University (BU), uses 3-D software to create detailed digital models of the birth canals of primates, from New World monkeys to apes to extinct hominins such as the Australopithecus afarensis known as Lucy. [1] [1] Editor’s note: Part of Laudicina’s research is funded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation, which publishes SAPIENS.

I first heard about Laudicina’s work when we met in southwest France in 2015 at the excavation of La Ferrassie, a site occupied by Neanderthals from about 100,000 to 45,000 years ago, and, later, by anatomically modern humans. My own work as an archaeologist focuses on some of the reasons why Homo sapiens persisted in Europe, while our close relatives, the Neanderthals, went extinct. Laudicina was at La Ferrassie to gain excavation experience, and as we worked, we talked about our respective subjects. I was fascinated by how the birth studies she was developing might address research questions similar to my own, and when this opportunity to write about her work arose, I contacted Laudicina and arranged a meeting with her to learn more.

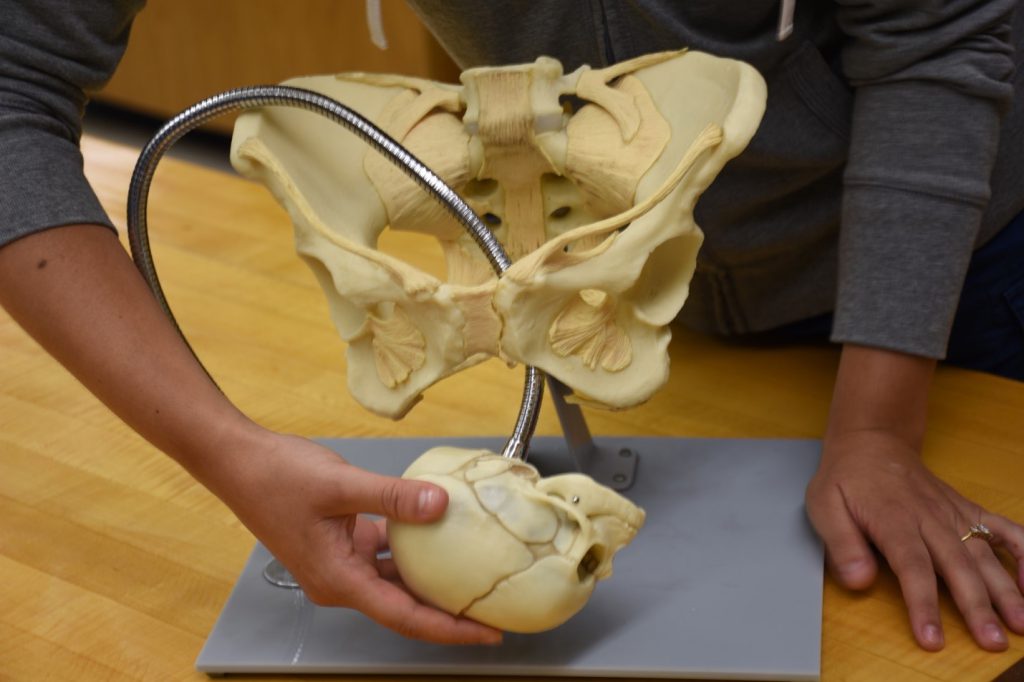

In early August, I visited Laudicina in the anthropology lab at BU, where for the past year she has been working with 3-D surface scans and measurements from the pelvic bones of female gibbons, colobus monkeys, chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, and other primates. She performs these scans on specimens from Harvard University’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. Later this year, she will travel to Europe to perform similar scans of early pre-human hominin and prehistoric human pelvic bones.

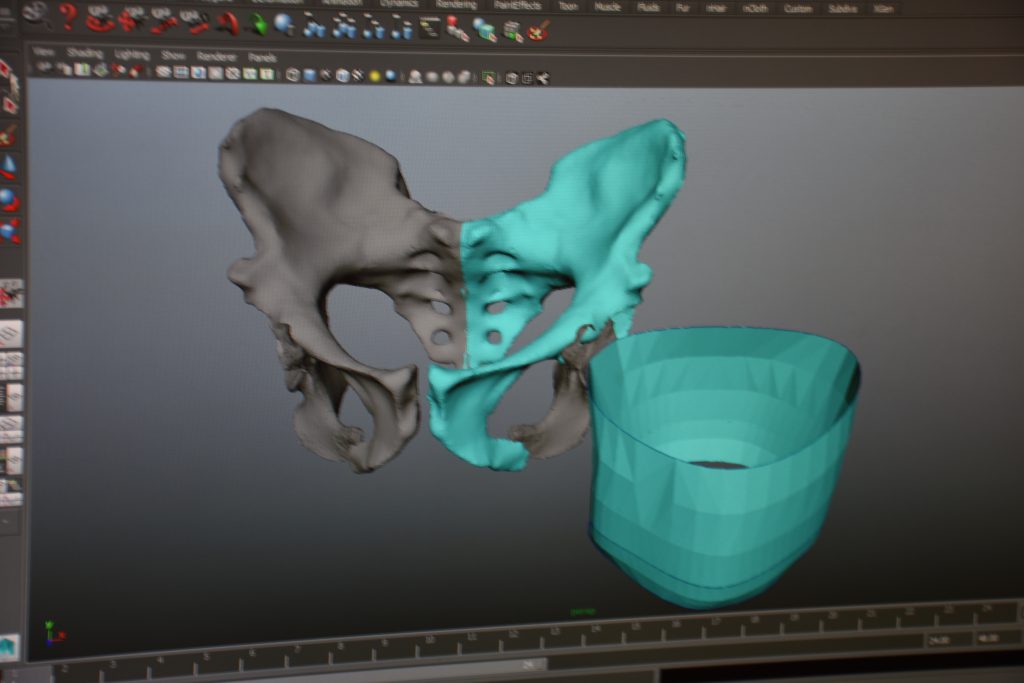

Laudicina sat me down at her workstation to walk me through the next stages of the process. After she has scanned and measured a pelvic specimen, she uses the 3-D software to create image “slices” drawn at 1-centimeter intervals down the length of the inner pelvis. Once she renders these slices, Laudicina stacks them, creating a detailed model of the internal shape of the birth canal. At that point, she generates a digital “baby” based on measurements of neonate cranium dimensions and shoulder breadth. She can then move the digital baby through the birth canal to see how the two interact. The result is a novel way to explore how the mechanics of birth shifted during the evolutionary processes that separated Homo sapiens from our primate and hominin relatives.

“The visuals you can get are pretty mind-blowing,” Laudicina told me, referring to the software. “It’s a new way of looking at a question that’s been around for decades.”

Laudicina became interested in the evolution of primate birth when she first learned during a graduate seminar that childbirth is one of the most dangerous events in a woman’s life. Her interest increased when she looked more closely at the statistics and was struck by the number of fetal injuries that occur during labor.

The wide, rigid shoulders of a human fetus often introduce major complications into the birth process. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, shoulder obstruction occurs in nearly 2 percent of births worldwide, and 25 percent of those cases result in fetal injury. To put these numbers into perspective: Based on data collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 3,978,497 births took place in the United States in 2015. If we apply the percentages above to this number, 19,892 of those births would have involved fetal injury as a result of obstruction during labor. Laudicina wants her research to contribute to a drop in fetal injury worldwide.

As we learn more and more about primate and early hominin life and behavior, the margin of difference between us and our ape and monkey cousins is shrinking rapidly. Tool use and bipedal walking—characteristics previously thought to be the sole province of humans—are now recognized elsewhere in the animal kingdom. Among primates, however, the mechanics of human birth are unique.

The human birth canal changes shape—moving from wide to narrow to wide again along its length. A neonatal ape passes easily through the mother’s birth canal without the need for rotation, and typically without assistance. As Laudicina put it, “A chimp or an orangutan or a gorilla could just squat and deliver a baby on her own.” In contrast, a human neonate must rotate twice during birth, a process that significantly increases the risk of complications and the need for assisted birth.

Is the shape of the human birth canal somehow related to our larger brains? Is it because we have wide-set shoulders, rather than the narrow, shrugged shoulders of an ape that swings from tree to tree? Is it a function of our bipedal locomotion? Laudicina’s set of models, once complete, will highlight the features of both mother and infant that could have affected the development of human birth over time. She hopes that when her study is done it will add nuance to our understanding of how the pressures of natural selection have affected the human pelvis throughout the course of human evolution.

The hours that Laudicina spends in her lab and in research facilities around the world will ultimately result in a means of “watching” births that we would otherwise never be able to see. By watching our closest primate relatives delivering babies—and by tracking the evolution of the birth canal throughout hominin history—she hopes to improve preventative care for women.

“Putting a mother on her back on a hospital table actually makes the birth canal more narrow and convoluted, and makes giving birth much harder than it needs to be,” Laudicina told me. “My hope is for this research to create dialogue about the best positions for mothers giving birth, helping doctors, midwives, and families to make better informed decisions.”