How the Folsom Point Became an Archaeological Icon

The Folsom spear point, which was excavated in 1927 near the small town of Folsom, New Mexico, is one of the most famous artifacts in North American archaeology, and for good reason: It was found in direct association with the bones of an extinct form of ice age bison. The Folsom point therefore demonstrated conclusively, and for the first time, that human beings were in North America during the last ice age—thousands of years earlier than previously thought.

The Folsom discovery marked the end of a long series of sometimes serendipitous, sometimes deliberate actions by an intriguing cast of characters. As such, it helps us understand that archaeology—like most fields of study—has very few “Eureka!” moments in which a brilliant sage comes upon an insight that suddenly changes the world. Instead, archaeology is cumulative, often slow, and painstaking. And while an individual artifact can indeed be important, its context (where it was found) and association (what it was found with) are often more important than the object itself.

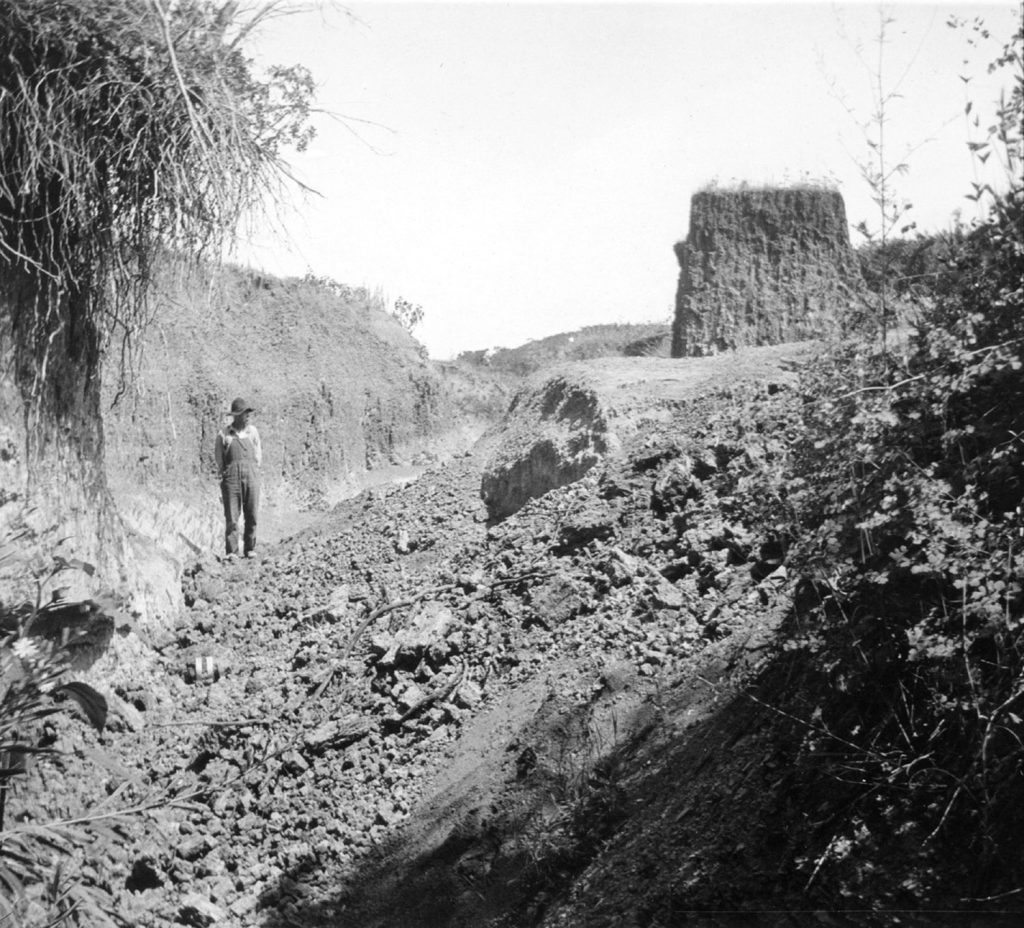

The story begins in 1908. In the late afternoon heat of August 27, an unusually strong summer thunderstorm dropped 13 inches of rain—75 percent of the yearly average—on Johnson Mesa, northwest of Folsom. The resulting flash flood swept through the town and the usually dry drainages in the vicinity. In so doing, it exposed buried features and artifacts that hadn’t seen the light of day in thousands of years.

A local cowboy named George McJunkin soon went out to inspect and repair fence lines broken by the flood. McJunkin was a fascinating character. Born into slavery in Midway, Texas, in 1851, he migrated west in 1868 to escape his awful past, and in Folsom he found a welcoming community. Though effectively self-taught as a naturalist, McJunkin maintained a collection of artifacts and specimens amassed during the long hours he spent chasing cattle. While surveying along Wild Horse Arroyo after the flash flood in 1908, he noticed large bones eroding out of a newly exposed wall at the base of the arroyo some 10 feet below the surface.

For 14 years after he made the discovery—until his death in 1922—McJunkin either kept the Folsom Site a secret or (more likely) was unable to convince anyone of its scientific importance. But on December 10, 1922, Carl Schwachheim, a naturalist and collector from nearby Raton, visited the Folsom Site with local banker Fred Howarth. Both must have known McJunkin; the community is very small even today. Perhaps McJunkin’s death had inspired them to finally visit the hard-to-reach site.

On January 25, 1926, Schwachheim and Howarth made a business trip to Denver. While there, they stopped by the Colorado Museum of Natural History (now the Denver Museum of Nature & Science [DMNS], where I work) to discuss the site and its contents with scientific experts. First they met director Jesse Dade Figgins, who told them to send bones to the museum for conclusive identification. Once they did so several weeks later, honorary curator of paleontology Howard Cook confirmed that the bones were from an extinct form of ice age bison, Bison antiquus. Cook’s identification and Figgins’ authorization finally set institutional and scientific wheels in motion.

Cook and Figgins went to the Folsom Site in early spring of 1926 to develop a plan of action; Schwachheim’s excavation team entered the field in May. Their goal was to secure an exhibition-quality bison skeleton for the museum—they had no way (yet) of knowing that the site contained evidence of ancient humans. Indeed, most scientific experts at the time thought that Native Americans had been in North America for only a few thousand years.

In mid-July, Schwachheim’s team discovered the base of a broken stone spear point. Unfortunately, they found it in a pile of the soil that had been removed by mule teams in order to gain access to the bone bed. As such, they could not prove it was directly associated with ice age mammals.

When told of the discovery, Figgins immediately recognized its scientific importance and potential. He told Schwachheim in no uncertain terms: If the team finds other points in the bone bed they should be left exactly where they are so that the deposit can be examined by specialists. Disappointingly, none were discovered that year.

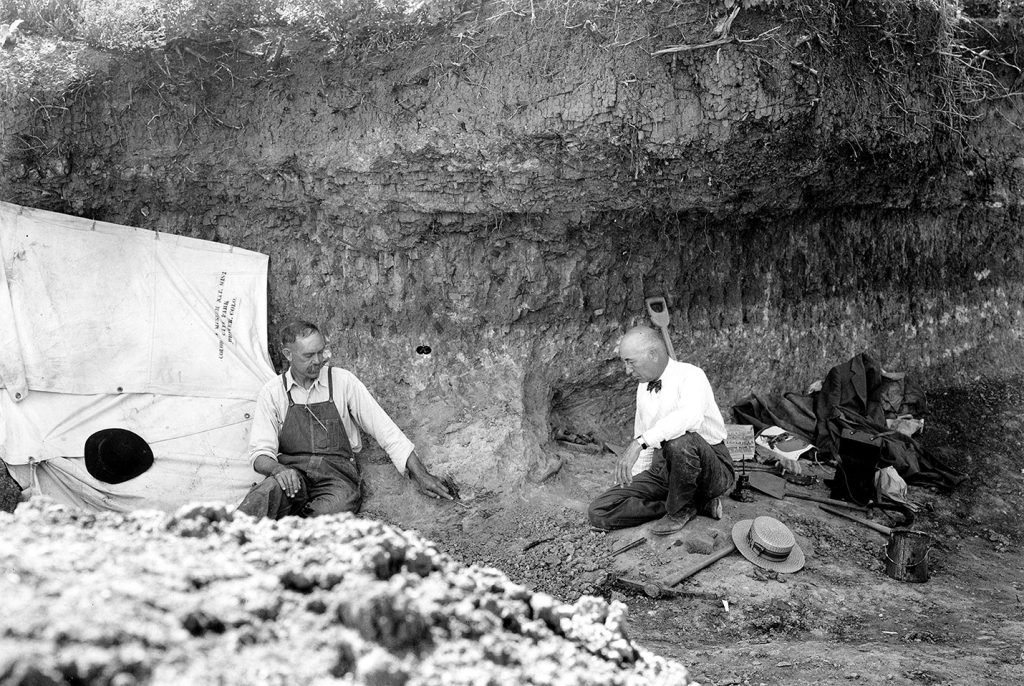

Schwachheim’s team returned to the site in 1927 with the exact same directive: Newly discovered points were to be left precisely where they were found until specialists could be called in. On August 29, the moment of truth finally arrived: They exposed a complete spear point between two bison ribs.

According to plan, Schwachheim telegrammed Figgins, who then contacted prominent archaeologists to announce the discovery and ask them to come see, and hopefully confirm, for themselves. Serendipitously, two of those archaeologists, though based on the East Coast, were already in Pecos, New Mexico—only 200 miles away from Folsom.

The wait, though less than a week in duration, must’ve been excruciating for Schwachheim and his team. They had worked for months under difficult conditions and now had to wait for specialists to confirm what they already knew—they had made a major scientific discovery. Over the next several weeks Alfred Vincent Kidder, Frank H.H. Roberts, and other specialists confirmed the initial field assessment: The point was indeed directly associated with the bison, proving that Native Americans had hunted large mammals during the last ice age. That Folsom point instantly became an icon, and it remains prominently on display at DMNS, still in its original sediment block.

The now iconic Folsom point was in fact the third spear point found at the Folsom Site. In addition to the broken point found in the soil pile in July 1926, Schwachheim’s team discovered a second point on July 14, 1927. For some reason, they ignored Figgins’ explicit directive and sent it, encased in a large block of sediment, to Denver. Figgins confirmed their discovery in the lab, but he knew from personal experience that they still needed a point in the field in order to convince the experts.

In 1924, Figgins had been involved in a remarkably similar project at the Lone Wolf Creek Site in central Texas. He had discovered Stone Age spear points in the laboratory, in sediment blocks that had been sent to the museum, just like the second point from Folsom. But he never found a point in the field at Lone Wolf Creek, which is why he was so adamant in his directive to Schwachheim’s team. Figgins must have been infuriated when their sediment block arrived in Denver in 1927. But he, like any good scientist, was patient, discerning, and critical.

The expert in-field confirmation that Figgins sought for so long, and eventually obtained, is the sole reason that the term “Folsom” is now given to a site, an artifact type, and a world-famous archaeological culture. By comparison, the Lone Wolf Creek Site is unknown, has no eponymous artifact type, and there is no archaeological culture bearing its name. Such is the nature of science.

Although the discovery and confirmation chapters of the Folsom story took place in both the field and the laboratory, it did not include research on museum collections. And it failed to answer some (now) basic archaeological questions: How old was the site, in years? How many animals were killed? Where did the raw material for the Folsom points come from? As we shall see in my next post, the Folsom story is still being written through the use of new analytical techniques and the reanalysis of archives and artifacts curated by museums.

This article was republished at discovermagazine.com.