What’s Wrong With “the Chinese Virus”?

Most Americans take it for granted that in the 1960s, more than 58,000 U.S. soldiers died in something called the Vietnam War. In Vietnam, however, there is no such thing as the Vietnam War. It is known there as “the American War.”

Anthropologists have known for decades that the names we give to things can be profoundly consequential. Words and names define the building blocks from which we assume the world is made up. They become our common sense. But seemingly self-evident words actually express a point of view. This may only become clear when we realize others have different building blocks or when the words are challenged.

Should a woman be addressed as Ms., Mrs., or Miss? Should driver’s licenses and passports offer people two or more gender options? Is alcoholism a “disease”? Does it matter if your boss calls you and your co-workers “girls” even though you’re all in your 40s?

And now, with the novel coronavirus pandemic, we have a new naming controversy.

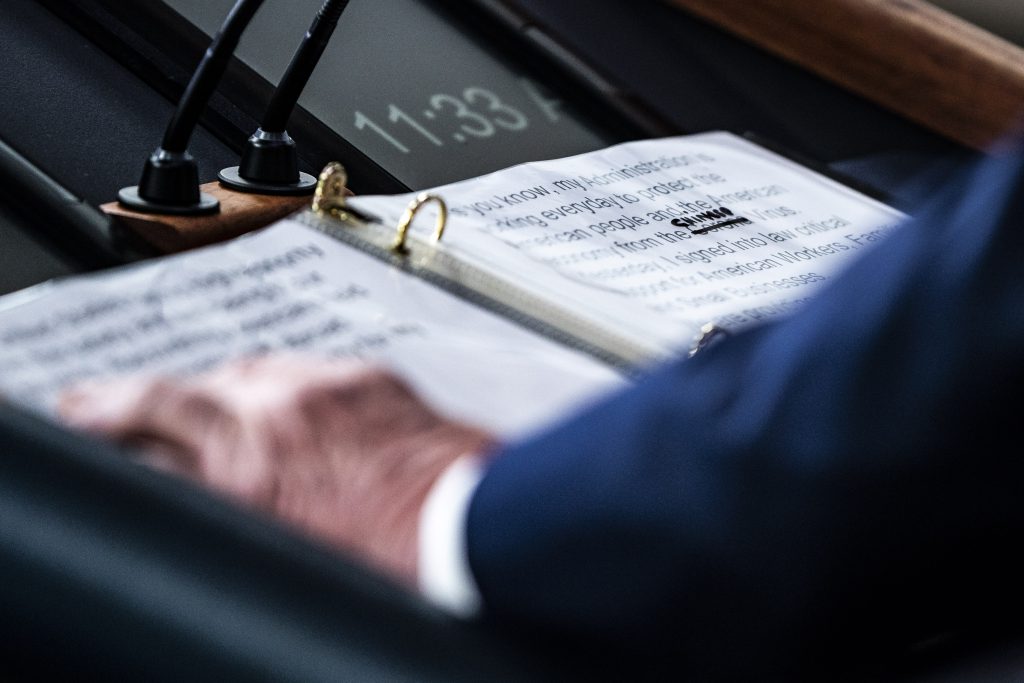

While medical experts label the virus by its formal classificatory title, SARS-CoV-2, and mainstream media call the disease COVID-19, U.S. President Donald Trump has repeatedly referred to it as “the Chinese virus.” One sharp-eyed press photographer even snapped a picture of Trump’s prepared remarks, in which he had crossed out “corona” and written “Chinese” with a sharpie.

Trump’s associates have also referred to the disease as the “Wuhan virus” and “Kung flu.” Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX) said “China is to blame” for the epidemic because in Chinese culture “people eat bats and snakes and dog and things like that.”

Accused by reporters, members of Congress, and public health experts of racism in his use of language, Trump explained his terminology by saying: “It’s not racist at all. No, not at all. It comes from China, that’s why. I want to be accurate.”

Defenders invoke the so-called Spanish flu and argue that there’s a tradition of referring to outbreaks in geographical terms. Before passing judgment, maybe it would help to step back and ask how other diseases got their names. How have we decided before to name things that can kill us?

Many diseases have names that reflect their symptoms. Tuberculosis was popularly known as “consumption” because its victims lost so much weight they were consumed by their illness. Mumps causes facial swelling that makes its sufferers mumble when they speak, and it is thought the word arose from the Dutch term for mumble, mompelen.

Measles was derived from the Middle English word maselen, meaning “many little spots.” Poliomyelitis (known more popularly as “polio”) comes from the Greek words for gray (polio) and marrow (myelon). And the common cold has been called that for centuries because its symptoms mimicked the effects of cold weather on people.

Other diseases memorialize their discoverers. These include Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, Tourette syndrome, and Crohn’s disease. Salmonella—a name the salmon fishing industry has lobbied to change—was named after veterinarian Daniel Salmon, who discovered it.

And some diseases come to be known, especially among lay people, by names that reflect ethnic prejudice or animus. In the 1860s, in a paper titled “Observations on an Ethnic Classification of Idiots,” what we now know as Down syndrome was named Mongolism because those with the syndrome supposedly resembled Mongolians. (The term “Mongolism” persisted into the 1980s, but the syndrome has now been renamed after one of the authors of that paper, John Langdon Down.)

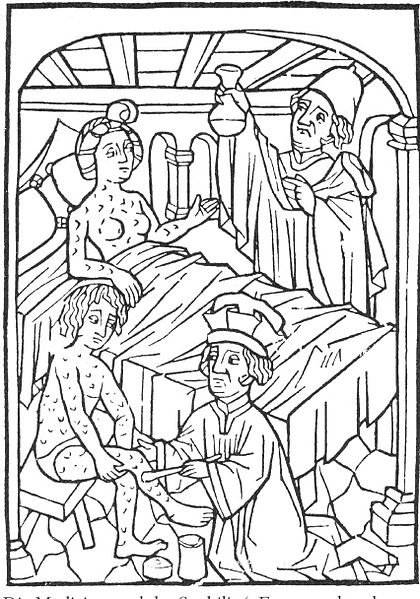

Diseases with ethnically loaded nicknames are often those that carry the taint of immorality. Many countries affected by syphilis blamed the sexually transmitted disease on neighboring nations’ licentiousness. The English historically referred to it as “the French disease.” The French returned the favor by calling it “la maladie Anglaise.” They also styled it “the Spanish pox.” The Russians dubbed it “the Polish disease.”

Incidentally, syphilis was introduced into the Americas, along with smallpox, by European colonists. Maybe we should brand it the “European infection.”

Is Trump’s characterization of COVID-19 in this tradition? Conservative commentators say no, pointing out that diseases have often been named after their point of origin. Lyme disease was originally identified in Lyme, Connecticut. West Nile virus was discovered in the West Nile district of Uganda. Ebola surfaced near the Ebola River in the Democratic Republic of Congo. And Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) was first reported in Saudi Arabia.

While such commentators are correct to observe that other diseases are anchored to specific areas through their names, we might note that those disease titles typically use place names rather than ethnic classifications. Thus, we have “Ebola,” not “the Congolese disease,” and “Lyme disease,” not “the American disease.” I imagine some Americans might be annoyed if people around the world deemed Lyme disease “the American disease.” As Congressman Ted Lieu (D-CA) observes, “There is a difference between saying the virus is from China and saying it is a Chinese virus.”

Moreover, the World Health Organization condemns the practice of naming diseases for places. The agency has said it particularly regrets allowing the term MERS to enter into circulation. In its official guidelines for naming novel diseases, WHO says, “cities, countries, regions, [or] continents” should be avoided in disease names because they unfairly stigmatize those places. It lists Lyme disease, MERS, and the Spanish flu as examples of inappropriate nomenclature.

“The Spanish flu” offers the closest parallel to Trump’s term “the Chinese virus.” And the parallel should give us pause.

This strain of flu, thought to have killed roughly 50 million people between 1918 and 1919, did not originate in Spain, and it killed more British, French, Germans, and Americans than Spaniards. However, those other countries censored coverage of the pandemic, while Spain did not, so it became known through Spanish media accounts.

The Times of London, refusing to report the flu’s death toll among British troops, christened the illness “the Spanish flu,” and the name stuck. (Incidentally, many Spaniards dubbed it “the French flu.”) Today health authorities have recognized the misnomer and typically call it the 1918 flu pandemic.

Labeling COVID-19 “the Chinese virus” fits with Trump’s geopolitical hostility toward China, as well as his pattern of identifying non-European foreigners with disease in general. At one point, for example, he said Mexicans were responsible for “tremendous infectious disease … pouring across the border.” Representing COVID-19 as invasively foreign also enables Trump to distract attention from his own administration’s dismal response to the spread of the disease in the U.S., implicitly affixing the blame to an ethnically defined “other.”

Trump’s terminology may have serious public safety and health consequences. In the U.S., there have been numerous accounts of Asian American adults and children being assaulted, verbally abused, bullied, and spat on by strangers accusing them of bringing the virus to the U.S. In one case, a man on the New York subway sprayed an Asian passenger with the deodorizer Febreze.

Meanwhile, in an astonishing display of ignorance that endangers the health of those he represents, one elected official in Kansas said that social distancing was unnecessary because so few Chinese people live in Kansas.

But maybe terms like “the Chinese virus” and “Kung flu” circulate in part because the official name, COVID-19, is so dull and dry. A more memorable name for the virus might inoculate us against pernicious naming practices that infect the body politic.

One possibility would be to name it after the animal from which it originated. In the case of COVID-19, scientists suspect it might be a bat or a pangolin, though they may never know for sure. “Bat virus” and “pangolin plague” do have a certain ring to them. And there is ample precedent for such names: mad cow disease, swine flu, and bird flu.

However, the World Health Organization prohibits naming diseases for animals, in large part because of the economic damage this can do to sectors of the farming and food supply industries. And scapegoating bats and pangolins could cause people to kill these animals, many species of which are critically endangered.

The WHO also disallows classifying diseases after people’s names. But it’s tempting to re-christen COVID-19 for one of the heroes of the pandemic, Yong-Zhen Zhang of the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center & School of Public Health at Fudan University.

On January 10, Zhang’s team in Shanghai published the DNA sequence of the novel coronavirus on open platforms and courageously recommended immediate public health measures at a time when Chinese officials were doing nothing. The Chinese government closed his laboratory within days.

The publicized genome helped researchers develop tests for the virus. And assuming we one day have a vaccine for COVID-19, it will be because of Zhang’s pathbreaking work and political courage. If the disease is to be identified with China, let it be associated with a Chinese scientific hero.