Between Male and Female

When Netflix premiered Orange Is the New Black in 2013, the show drew legions of fans largely because of its unique setting (a federal women’s prison) and its diverse cast of characters. In a sea of orange jumpsuits, one character stood out: Sophia Burset, a black transgender woman whose story took center stage when prison officials abruptly denied her hormone replacement therapy pills without her consent. Born with biologically male sex characteristics, Burset underwent sexual reassignment surgery and began a lifelong course of synthetic estrogen to more visibly express her female gender identity. Without supplemental hormones, she would likely experience masculinization, such as facial hair and reduced breast size, as well as emotional and physical pain.

The following year, MTV premiered Faking It, a stereotype-fighting show set in a Texas high school in which popularity is gained by being different from the norm. The cast of characters includes a wide range of minorities, such as the Muslim, hijab-wearing journalist Vashti, the bisexual man Felix, and the trans-homeless character Noah (who is, notably, played by a trans actor). One exception is Lauren Cooper who, as a white, blonde, and conservative woman, appears to be a foil to the other characters. Soon enough, however, viewers learn that Lauren is intersex. The term intersex, according to the Intersex Society of North America, refers to a variety of conditions in which a person “is born with a reproductive or sexual anatomy that doesn’t seem to fit the typical definitions of female or male.” Transgender, on the other hand, refers to people whose gender identity or expression does not conform to their birth-assigned sex.

But while transgender and intersex characters are becoming more common in popular culture, the male/female binary remains one of the most fundamental in Western societies today. For forensic anthropologists and the law enforcement communities they aid, the he/she binary is the primary building block of a “biological profile,” a description of a person’s physical characteristics. That’s helpful because when a set of human remains is identified as male or female, half the population from a pool of missing people can be disregarded.

However, characters such as Burset and Cooper, and their respective transgender and intersex compatriots around the world, disrupt the idea that human bodies must be male or female. Their bodies do not fit neatly into either category but rather force a spectrum approach to traditional biological sex classifications.

It’s not clear how many trans and intersex people there are in the world. A widely cited estimate is that in the United States there are 700,000 trans individuals, but many experts believe the figure is higher. According to a report published on the website Practical Androgyny, around 0.4 percent of Britain (England, Scotland, and Wales) identifies as “nonbinary,” which in this case is used as an umbrella term to encompass “any gender (or lack of gender) that would not be adequately represented by an either/or choice between ‘man’ or ‘woman.’ ” This report relies in turn on statistics culled from a 2012 paper published by the Equality and Human Rights Commission that outlines and suggests best practices for social scientists to ask questions regarding gender identity. In contrast, the Intersex Society of North America bases its intersex birth-rate estimates—1 in 1,666 births—on this 2000 study in the American Journal of Human Biology, which was a review of the literature produced between 1955 and 1998.

It is necessary to point out that this rate (1 in every 1,666 births) is a specific calculation based on how many individuals displayed chromosomes that were not XX or XY. The rates for other nonbinary sex chromosomal variations differ. For example, the type of intersex chromosomal variation Lauren Cooper displays—androgen insensitivity syndrome—occurs at a much lower rate: 1 in every 3,000 births.

The bodies of trans and intersex individuals are inherently problematic to our current system because they cannot be easily categorized. Would forensic anthropologists be able to accurately identify women like Burset and Cooper?

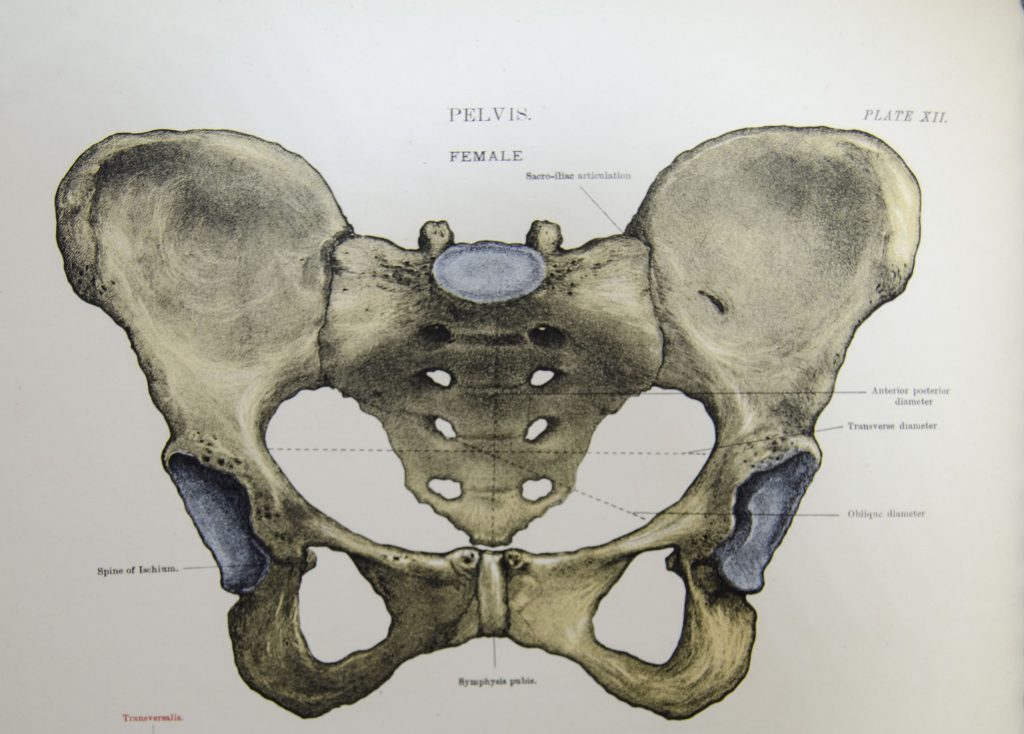

Exceptions to the male/female binary challenge the current practice of forensic anthropology, right down to the terminology we use. In producing a biological profile, forensic anthropologists first turn to the pelvis—a bone that, if available and in one piece, is the best sex-related skeletal indicator, proven over multiple studies to be accurate 95 percent of the time. In evaluating the presented sexual characteristics of a set of human remains, forensic anthropologists use the term biological sex to refer to the skeleton’s physical sex characteristics, which may or may not reflect the gender of the person. As a shorthand, we say that we are “assigning sex,” which is a problematic turn of phrase, as it perhaps places too much power in the hands of anthropologists.

In assessing physical sex characteristics, an anthropologist evaluates the pelvis on a scale of 1 (meaning “very female”) to 5 (meaning “very male”). For example, male pelvises are “taller” in that their iliac crests are more vertical, whereas female iliac crests tend to be “flared” to accommodate a potential fetus. After tallying the scores of several segments of the pelvis (each of which is individually given a score between 1 and 5), the anthropologist decides if the skeleton is more male or more female. A spectrum is necessary because skeletal remains do not always fit into a simple binary. Indeed, some pelvises are marked with a number 3—meaning that they likely contain an equal number of male and female components, or they are too nondescript to be assigned a sex category. If a pelvis is scored as a 3, anthropologists are trained to “assign” its sex as “undetermined” or to simply give it a question mark.

No further guidance is offered to those in forensic anthropology as to what to do about pelvises marked with a 3. There are no studies on the relationship between nondescript pelvises and the remains of intersex or transgender individuals. A premier text, Forensic Anthropology: An Introduction, published in 2012, uses the word intersex once, only providing a working definition for the term. It does not address how to evaluate whether or not a skeleton is intersex. Furthermore, it does not use the term trans at all.

Forensic anthropologists have long accepted that no skeleton is completely male or female from birth, but most have little understanding of the murky middle of the spectrum. The human body already shifts between displaying traditionally “male” and “female” skeletal characteristics during a human’s lifespan: Just look at the human jaw. We all lose our baby (deciduous) teeth, which are then replaced with permanent adult teeth. But if we lose an adult tooth, there is no new tooth to replace it and the socket begins to resorb, as bone resorption outpaces bone deposition. In a male, if enough teeth are lost, the entire jaw regresses and will take on the appearance and structure of a female jaw—this is because the “original blueprint” for all human bodies is female. This phenomenon could lead an anthropologist to mistake a set of remains as female in death, even if the person was male.

With transgender and intersex individuals, forensic anthropologists face additional challenges. For example, what does the human skeleton of an individual who undergoes sexual reassignment surgery and the ensuing hormone replacement therapy to change from a male to a female look like? What are the unique characteristics of a human skeleton that contains aspects of both maleness and femaleness from birth? What should a forensic anthropologist do with this information, other than writing off these skeletons’ sex category as “undetermined”—and how might it relate to all those problematic pelvises categorized as 3s? Such ambiguity prevents us from finding out who the people these remains belonged to really were. It is no longer enough to assign a label of “nondescript” or to say, “I don’t know.”

In today’s world, human variation and bodily differences, particularly of underrepresented groups, can sometimes become more acceptable through our entertainment. The Cosby Show, for example, undeniably changed how many viewed middle-class, African-American family life (the recent accusations against its titular character notwithstanding). The most recent iteration of the African-American family sitcom, ABC’s black-ish, devoted an entire episode to The Cosby Show’s lifelong impact on its characters’ lives. Another TV example is Modern Family, a show that features a white, gay couple as part of the main cast. Media critics and academics alike credit Modern Family with altering perceptions about gay couples—particularly with respect to their roles as caregivers and parents. TV sitcoms can be a stepping stone for underrepresented populations to find a place in the wider cultural narrative, prompting reconsideration and acceptance through storytelling with sympathetic characters. Just as The Cosby Show and Modern Family encouraged many viewers to reassess their understanding of “family,” shows like Orange Is the New Black and Faking It are pushing many to rethink their assumptions about what it means to be “male” or “female.”

Can these TV shows change forensics? They can certainly open up the minds of scientists working in the field, which can lead to new approaches to education and research. But real change will be slow going, as forensic science requires thousands of bodies to produce workable formulas for identifying unique traits among populations. Laws that regulate human remains are another barrier. The United Kingdom’s Human Tissue Act, which requires consent for the removal, storage, use, and display of human tissues and remains that are less than 100 years old, and thus limits the number of available remains for study, is a huge impediment for advancing research on intersex and trans bodies. The United States appears to be more lenient in its legislation; the Public Health Service Act and the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, both under the arm of the Food and Drug Administration, regulate issues of human tissues and remains, but only insofar as they apply to the spread of communicable disease and the use of tissue-based products.

With academic research institutes, such as the Forensic Anthropology Center’s Research Facility at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville (colloquially known as the “Body Farm” because its focus is on human decomposition), there is more opportunity to improve forensic anthropology in the United States. Longitudinal studies of trans or intersex individuals undergoing hormone therapy would be one way to advance this research; for instance, forensic anthropologists could partner with endocrinologists to track the changes to the human pelvis when someone begins taking synthetic hormones. Measuring the long-term effects on the skeleton would help inform biological profiles of transgender and intersex bodies.

Researchers should continue to explore the full biological spectrum of the human body, as well as contribute to important discussions about remains that don’t fit the standard binary model. One way to start training the next generation to question their assumptions is to teach students that a pelvis scored as a 3 is not simply unclassifiable—it may perfectly represent the human body it resided in. When cultural knowledge and social acceptance of different biologies become normalized, along with new scientific categories to accommodate them, it helps us all—forensic anthropology and society at large—to better understand ourselves.

Correction: June 29, 2016

An earlier version of this article stated around 0.4 percent of the United Kingdom (England, Scotland, and Wales) identifies as “nonbinary.” Although “United Kingdom” is used in the Practical Androgyny site, the original findings in the 2012 paper are for Britain (England, Scotland, and Wales), not the United Kingdom.