How Traditional Knowledge Opens Nature’s Medicine Cabinet

Under the clear, moonlit sky of Friday, July 13, 2018, Elide Sanchez Rivera steps into her own star—a large, white symbol chalked into the dusty ground. With the sound of the ocean waves crashing nearby, Sanchez stands in front of an altar and waits for the healing to begin.

For the last 2,000 years, if residents along the northern coast of Peru were sick, they could seek out a curandero, one of the region’s shamanistic healers. Their treatment would consist of a nightlong diagnosis whereby the curandero and perhaps some family members would gather with them around a symbolic altar known as a mesa. Here, strategically placed power objects such as bottled herbs, sacred images, or magnetic stones would represent opposing forces—good and evil, old and new, masculine and feminine—and be arranged around a central point of harmony. The Andean healer’s mission was, and still is, to restore a patient to balance, allowing them to accept the natural flow of extremes without being swayed in one direction or another.

After the ceremony, the curandero would prescribe a treatment for the weeks or months to come: typically, a mixture of precisely prepared medicinal plants and suggestions for lifestyle changes. Such millennia-old healing rituals are still common in northern Peru today—and now, remarkably, some of these ancient medicines are becoming accessible at national clinics across the country.

In the late 1990s, Peru’s social security health insurance program, EsSalud, developed the National Program of Complementary Medicine and opened three centers in the country’s major urban centers of Lima, Arequipa, and Trujillo. Now 29 such centers exist, offering a range of alternative treatments that include the medicinal plant therapies historically prescribed by curanderos.

This move takes advantage of Peru’s rich diversity of flora and traditions to offer affordable and accessible treatment options to as many people as possible. It’s an innovative approach. But the program has faced multiple hurdles in actualizing its vision. As yet, only a narrow selection of plants is available through the clinics, ensuring a sustainable supply is a challenge, and many potential patients remain suspicious, reticent, or simply unaware of the new treatment options.

Help, however, is coming from an unlikely source: anthropology. For almost two decades, researchers in the U.S. and Peru have joined forces to understand the ethnobotany and medical anthropology of medicinal plant use in urban and rural communities near Trujillo, north of Lima, Peru. They have been tapping into knowledge that was nearly lost due to the persecution of curanderos during Spanish colonization of the New World.

“We are motivated by the chance to improve people’s lives through the direct application of cultural anthropology,” says anthropologist Thomas Love from Linfield College in Oregon. “These plants are the first line of people’s health.”

The studies to date have helped mine the wisdom buried in age-old healing traditions and have also yielded insights into the essence of what constitutes true healing—socially, emotionally, and physically. As such, the investigations are not only uncovering treatments that could benefit modern medicine but are also revealing potential pathways to holistic health in Peru and beyond.

On a July day in 2018, Luis Fernandez Sosaya strolls around EsSalud’s complementary health clinic in downtown Trujillo while giving two anthropologists a tour. Fernandez, a physician, coordinates the clinic and is, himself, a pioneer of the program.

The anthropologists are the 2018 field leaders of the Minority Health and Health Disparities International Research Training Program in North Peru funded by the National Institutes of Health in the United States. One is Douglas Sharon, a co-founder of the program, which is based out of San Diego State University, and the other is Love.

A cacophony of taxi horns, revved engines, and good-natured shouting blares outside, but inside the stately colonial building, an aura of tranquil healing prevails. The burble of water fountains gently mixes with the sound of Mozart, and a light breeze carries the scent of flowers from the clinic’s courtyard garden. “The environment, and natural beauty, is an important part of healing,” Fernandez says.

The men walk from the garden, where many of the medical plants prescribed by EsSalud physicians grow, to the natural pharmacy. There, Fernandez proudly shows the anthropologists where the medicinal parts of plants such as horsetail and cat’s claw are neatly packaged to administer to patients who have a prescription. At present, Peru’s clinics offer medicinal plants—each of which has undergone years of rigorous testing for safety and efficacy—in their pharmacies. Clinicians carefully prepare, store, and stock the plants and their extracts to ensure full effectiveness and a consistent supply for patients.

Peru’s innovations in public health began nearly 30 years ago. In 1991, Peruvian physician and scholar Fernando Cabieses, a senator at the time, founded (and later directed) the country’s Institute of Traditional Medicine within the public health system. For the next 10 years, Cabieses pioneered many projects, including the establishment of a network of botanical gardens throughout Peru and a series of scientific papers on the safety, efficacy, and quality control of 200 widely used medicinal plants in the country.

At the same time, Peru’s public health system was encountering new challenges. The country’s citizens—as in many parts of Latin America—were aging and facing the modern epidemics of hypertension, diabetes, and cancer, which strain the health care system. To address the increasing demand on resources, EsSalud was created within the social security system to serve the health-insured working class and their families, focusing on prevention, as well as treatment, of these diseases, which are often lifestyle-linked.

EsSalud also wanted their prevention program to be sustainable and available to as many patients as possible. The clinics needed to find treatments that clients could afford, so they made use of the resources available. “It doesn’t make sense that a country that is as rich in plants as this isn’t using them,” Fernandez says. “And there is a huge body of traditional knowledge and wisdom surrounding the use of the plants.”

Consequently, the EsSalud pioneers chose phytotherapy—the science-based use of plants in medicine—as one of the first clinical treatment modalities to embrace. EsSalud chose the 20 most thoroughly researched plants to use in its clinics at the start of the program, a mere fraction of the number used traditionally by curanderos and the local communities. In 2001, the country collaborated with the World Health Organization to compile a manual summarizing the available scientific literature on 76 medicinal plants and the illnesses they could treat.

An early study comparing the use of complementary medicine with conventional medicine within EsSalud found alternative approaches—such as medicinal plant therapy and acupuncture—scored better in efficiency, patient satisfaction, and reduction of future risks in treating and preventing several disorders, including osteoarthritis, tension, migraine headaches, and obesity. In 95 percent of case studies reviewed, they also proved less expensive. Ongoing annual evaluations by EsSalud show that many patients are able to stop all prior uses of pharmaceutical drugs.

Still, trying to determine which of the wealth of available plants might have medicinal properties proved to be a formidable and complicated task. That is, however, without looking to the substantial body of knowledge passed down through generations of communities that have used medicinal plants for centuries.

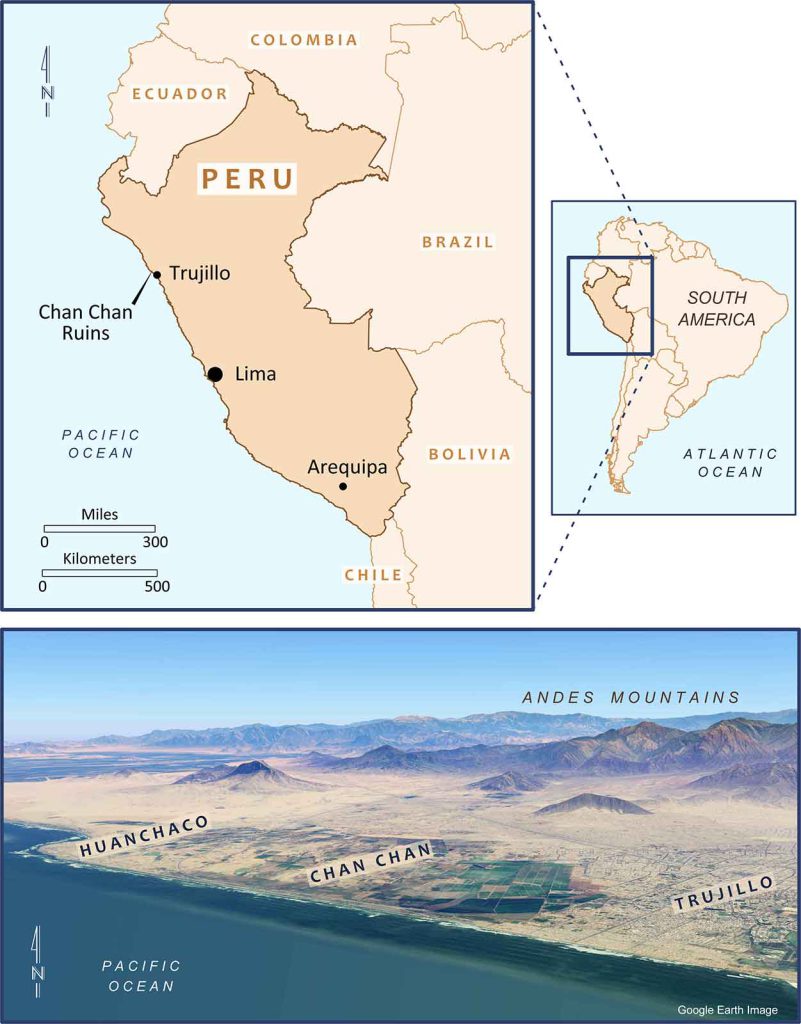

In the bleak coastal desert of northern Peru, right next to the ocean and less than a couple of miles from Trujillo, lie the remains of Chan Chan, the ancient capital of the Kingdom of Chimor. Six hundred years ago, this formidable city possessed more than 10,000 adobe structures. Decorated friezes, hundreds of feet long, lined the palaces and temples. Now, the stark, sand-colored walls mark a sharp contrast with the clear, blue sky, and the only inhabitants are clusters of crows. It was here that Sharon’s decadeslong fascination with curanderos began.

In 1957, Sharon dropped out of high school in Canada to join an archaeological explorers’ group in Peru, and in 1965, he ended up at Chan Chan. In the process, he met Eduardo Calderón Palomino, a trained artist in charge of restoring the animals and geometric shapes that adorned the friezes. Calderón was also a curandero; he used rituals, intuition, and herbs to heal his patients.

Curanderos, Sharon learned, practice throughout Peru and specialize in local plant use. In the North, these shamans use the psychoactive San Pedro cactus, whereas in rainforest areas, curanderos are more likely to use a psychoactive brew of ayahuasca. Once respected and well-rewarded for their treatments, curanderos were persecuted by Spanish colonizers beginning in the 1500s. A deep-seated prejudice against curandero practices persisted until recently.

Calderón was an extrovert who took great pride in the services he provided to his community. His attitude and work inspired Sharon, who would go on to pursue a degree in cultural anthropology and become Calderón’s apprentice. In 1978 and 1979, the two men taught a course on traditional medicine to medical students at the University of Trujillo’s School of Medicine. Calderón died in 1996, but Sharon’s network of curanderos expanded: He has studied and worked with 15 curanderos to date.

In 1981, Sharon took the directorship of the San Diego Museum of Man, and his fieldwork on medicinal plants extended to Ecuador in the 1990s. He teamed up with ethnobotanist Rainer Bussmann, who had become the scientific director of Nature and Culture International in Loja, Ecuador; the two researchers studied traditional medicine and the use of medicinal plants in Ecuador and Peru.

When, in 1999, Peru’s EsSalud began to explore the use of medicinal plants, Sharon immediately saw that his research with Bussmann could help the endeavor. “It was a great opportunity—the door was opening and I realized that, hey, a botanist and an anthropologist can do a lot here,” Sharon says.

Sharon and Bussmann started their own program to determine the broad range of medicinal plants used by curanderos over generations. “These people are living libraries of this heritage,” Sharon says.

The two scientists worked with their network of curanderos to build and publish a database of 512 medicinal plant species and 974 botanical mixtures that healers employed to treat various ailments. “When I first started to document medicinal plants with Eduardo Calderón, I thought, We’ll get a few dozen. But late into the afternoon, I had to turn the tape recorder off and continue the next day because he just kept going and going and going,” Sharon says. “And it was all carried around in his head. None of this was written down.”

In their analysis, the researchers found that the curanderos applied the plants catalogued in the database in more than 2,000 different ways. Sometimes, separate parts of the plant would be used topically for certain conditions, orally for others. The curanderos selected more than 40 percent of the plants to treat “nervous system” disorders. They also treated respiratory problems, kidney and urinary tract ailments, cardiac and circulatory disorders, rheumatic and arthritic conditions, and female reproductive system problems. “A lot of treatments from curanderos are for diseases where stress might play a role, such as autoimmune diseases, arthritis, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel, and psoriasis—long-term diseases that Western medicine doesn’t have a good handle on,” Bussmann says.

Bussmann, as a botanist, began to place the information into a scientific framework. In the 1990s, students went out to collect the plants in the field and in local markets, and prepared herbarium specimens. In 2005, U.S. and Peruvian scientists began working in local laboratories to characterize the composition of the plant extracts, verify that the plants used to treat infectious entities had antibacterial properties, and test if the plants were toxic.

The laboratory studies revealed that most of the extracts from 141 plants used to treat infectious disease showed antibacterial activity. Gail Willsky, a biochemist at the University at Buffalo who became involved in the project in 2011, believes that there is the potential for Western medicine to learn from the curanderos’ use of the plants. Fifty years ago, no one knew that bacteria could cause ulcers, but now medicines that kill the bacteria, Helicobacter pylori, are a standard treatment for ulcers. “So it is interesting to see what the curanderos are using to treat conditions we don’t think of as infectious,” Willsky says.

In 2011, when Sharon believed that they had enough verified information to be of value to EsSalud, he approached Fernandez to offer the group’s assistance. The anthropologists have contributed to EsSalud’s efforts ever since. They continue to collect information on medicinal plants, document cultural familiarity with this therapy, and investigate the extensive knowledge and worldview of the curanderos.

It’s a cool, misty morning in Huanchaco, and the fishermen are out in their caballitos de totora, a style of reed boats used in the region for thousands of years. On the hill stands one of the oldest churches in Peru, but, in contrast, modern restaurants and trinket stalls line the seafront, catering to the steady stream of tourists.

Against this eclectic backdrop of ancient traditions and contemporary influences, Love and Sharon’s students have spent weeks knocking on doors to find out householders’ knowledge about, and use of, medicinal plants. They also documented the interviewees’ perceptions and preferences regarding Western and traditional medicine. By early July, each student had conducted 100 interviews in Huanchaco and the nearby town of Huanchaquito.

Sharon started such surveys in clinics in 2002, and Love joined him in these studies in 2009. To date, they have found that northern Peruvians typically have a great deal of knowledge about traditional herbal therapy and continue to use it as an alternative to Western medicine. “The thing that struck me is how basically pragmatic the people are,” Love says. “They are happy to use both medicinal plants and pharmaceuticals.”

Indeed, in the public, private, and herbal clinics in Trujillo and its neighboring communities, people have an almost equal preference for traditional and Western medicine. The students’ recent findings show that convenience, cost, and familiarity factor into a person’s final choice.

“Many people say that they would use either plants or pharmaceuticals, but they would often choose Western medicine because it works faster,” says Kennedi Dean, who is studying in the life sciences at Howard University in Washington, D.C. According to San Diego State University student Francisco Hernandez, the number of pharmacies in Huanchaco makes it more convenient to use pharmaceuticals, despite people’s preference for medicinal plants.

Understanding local knowledge about traditional medicine could update EsSalud’s plant database and help clinics in their outreach efforts. EsSalud wants to help communities understand that the clinic is an additional resource for healthy living and that medicinal plants are a science-backed therapy, not only a cultural tradition passed down through generations.

Sharon and Love’s research teams are also identifying culturally bound social and emotional ailments that many Peruvians claim can only be treated by a curandero. These include conditions such as “fright,” “shame,” and the “evil eye,” a malady brought about due to envy or bad will from someone else. Previous studies have revealed that 90 percent of people interviewed believe in or know about such ailments. For the students, several of whom plan to train as doctors or anthropologists, these ideas highlight how cultural and social factors play into human health.

Many Peruvians appear to value both a mental and physical approach to disease, Love says. “We need to understand the way they think about illness,” he says. “They see it as having psychological and social aspects as well.”

To Elide Sanchez Rivera, these ideas are familiar. Like the others in her cohort, she is American-born, and, like three others in the group, her parents moved to the U.S. from Mexico. Sanchez’s grandmother knew how to treat people with medicinal plants, including how to cleanse people of the “evil eye.” When she and Love and Sharon’s other students were offered the opportunity to participate in a healing ritual with Julia Calderón de Ávila, longtime curandera and daughter of Eduardo Calderón, Sanchez jumped at the chance.

Once Sanchez stood in the white star, the chanting, whistling, and rattle shaking began. Calderón lit incense and began to spray a mixture of cornmeal, clear-colored perfumes, and white flowers over Sanchez in a ceremony designed to root out any negative influences in her life. The curandera’s mission is to help her patients move forward with clarity and confidence in body, mind, and spirit.

Although the scope of EsSalud’s interest has concentrated on curanderos’ knowledge of medicinal plants, Sharon stresses their value doesn’t lie solely in that tradition. Curanderos, he says, “have an acute, intuitive sense about people,” and in Latin America, people call this intuitive capacity to look into a person’s soul el don (the gift). He believes that this talent is the essence of the curanderos’ healing ability.

During the five decades he’s worked in Peru, Sharon has seen some encouraging developments in attitudes toward previously persecuted curanderos. In 2015, the Ministry of Culture began an initiative to acknowledge the curanderismo of the northern coastal region of Peru as “cultural patrimony of the nation.”

“If this comes to fruition, it will be a huge step forward,” Sharon says. Also, EsSalud invited Julia Calderón to the 2018 World Congress on Medicinal Plants and Natural Products Research. “Another small step,” he says.

Sharon believes that the future lies in recognizing the role of curanderos in nurturing public health, a vision that would require a greater recognition of this ancient traditional healing practice. But that need not mean fully integrating traditional medicine and the curanderos into the public health system. Rather, Sharon envisages the curanderos and EsSalud on parallel tracks, each healing the public and, on occasion, collaborating with one another.

Such an arrangement would echo the curanderos’ emphasis on wholeness and completion through weaving together opposites—what Sharon refers to as the “Peruvian yin yang.” Old and new, traditional and modern, would work in harmony to bring each patient, and their health care system, to a point of balanced well-being.