The World Hates Fat People

As a child, Mia watched her mother struggle to recover from stomach-stapling surgery. She recalls her mother enduring obvious, miserable pain for years after the weight-loss procedure. Once, after a fruitless effort to comfort her mother during an intense episode of vomiting, Mia asked, “If you had it all to do over again with all of this, would you do it again?” Her mother responded, “Oh yeah, in a heartbeat … because the world hates fat people.”

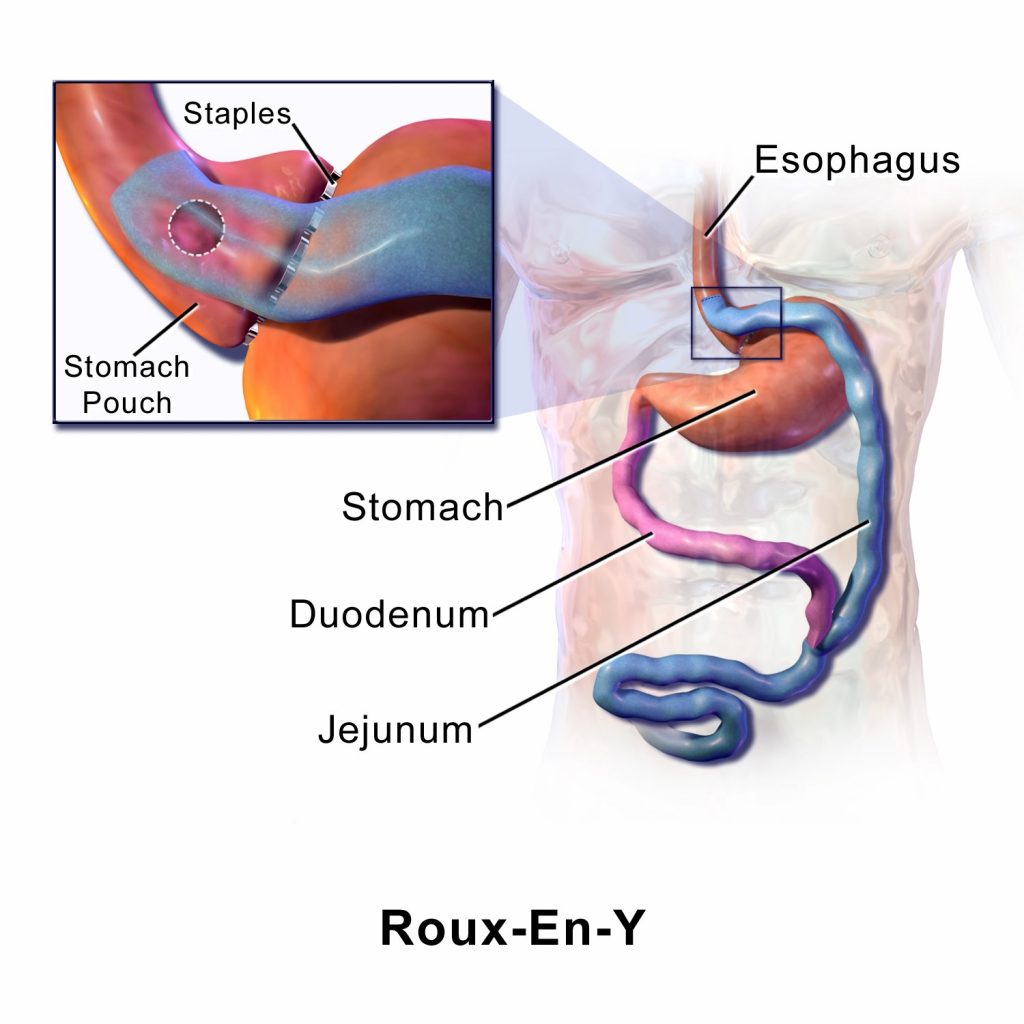

In early 2015, when we first met and began interviewing Mia (a pseudonym), she was preparing to undergo Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery at age 39, after a lifetime of struggling unsuccessfully with her own ever-increasing weight. The surgery reduced the size of her stomach while “bypassing” part of her gut. Since the surgery, in spring of 2015, Mia has lost over 100 pounds. Despite many painful complications in the wake of the surgery, she echoed her mother’s sentiments in her second interview with us: that the weight loss more than compensates for any physical suffering. She is happier and more self-confident with her smaller body.

Sitting in a coffee shop with us near the end of 2015, she reflected on the fact that just one year before, she would have quietly gotten her drink and left, feeling certain—based on decades of experiencing nasty comments and negative feedback at home, school, work, and out in public—that everyone was staring at her, judging the amount of space she took up. She noted that, on this occasion, she chatted comfortably with the barista and then with a bystander while waiting for her tea. For her, she said, these small changes were important signs of a better and more “normal” life, one in which she could establish friendships, advance in her career, and interact with strangers without enduring judgments based on her size.

Mia is a participant in a study we have been conducting with bariatric surgery patients since 2012. Using a variety of research methods—including semistructured interviews with 35 bariatric patients (25 of whom returned, like Mia, for second and third interviews), a survey with 296 bariatric patients (most of whom are completing a follow-up survey at the time of this writing), and participant observation within a bariatric program with literally hundreds of patients and roughly a dozen providers—we have been examining the ways in which surgically induced weight loss reshapes people’s sense of self and their social lives. This research is part of a larger set of cross-cultural studies in which we track the social, emotional, and physical implications of body norms around weight.

In the past decade, we have interviewed thousands of people who are trying to lose weight. We’ve found that excess weight is a source of concern for the overwhelming majority of people who have it. This holds true in each and every one of the groups we’ve studied: housewives in Paraguay, college students in the United Arab Emirates, villagers in Samoa, migrants in Mexican border towns, and teens in the American Southwest, to name a few.

Not only do diverse groups of people express worry over their weight, but in many instances they consider their personal anxieties about weight to be just as important as concerns about economic instability, political chaos, and experiences of violence inside and outside of the household. We have heard many stories about people’s stressful experiences engaging in weight-loss endeavors. These stories converge on similar themes despite undeniable cross-cultural differences in ideas about fat, health, the “ideal” body, disordered eating, a “good” diet, and much else.

Concerns about physical health and mobility, as well as emotional and social problems, influence people’s desire to lose weight. In our research with bariatric surgery patients, many men and women reported that they sought this particular medical intervention because their weight caused them to struggle with chronic conditions like diabetes or joint pain. Many also yearned for an escape from the complex webs of blame and self-doubt that were tied to their fatness.

Even as some scholars suggest that the Western (and increasingly global) medical and social obsession with getting rid of fat is morally questionable, Mia and many others we interviewed have a different perspective. For them, the chance to be “not fat” is well worth a lifetime coping with the aftereffects of surgery, which may include restricted eating, bouts of nausea, gut pain, and the indignities and discomfort of excess skin.

A depressing truth has emerged from our cross-cultural studies of weight and weight-loss efforts—individualized blame and shame around excess weight have become a global phenomenon. Throughout human history, notions of health and body ideals—and views about where the responsibility for one’s weight lies—have been more diverse than they are today. The individual was not always (or even often) seen as solely responsible for their weight. This appears to be changing around the world.

Part of the current stigmatization of excess weight results from health-related messaging. We inhabit a world in which many different stakeholders actively encourage people to work harder and harder to lose weight. In recent years, major national anti-obesity efforts have been launched, including Mexico’s Nuestros Niños Son Primero (Our Children Come First), New Zealand’s Big Change Starts Small, and Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move campaign in the U.S.

In addition, narratives pushed by magazines, television shows, and social media emphasize particular body norms of thinness. And a voracious multibillion-dollar dieting industry reassures us that it is easy to drop pounds and shave inches—with the right product or plan, of course. This industry not only promotes weight loss but also suggests how much better life will be when it happens. The messages about why we need to lose weight, and why it needs to happen immediately, bombard us—not only in wealthy Western nations but increasingly in less-wealthy parts of the world.

Does this constant, now global, talk about the need for weight loss actually help people lose weight, including those technically classified as “obese”? It certainly motivates people to try to lose weight. If you look at actual weight loss, however, it is evident that such talk, particularly on the part of governments and public health initiatives, registers as a big, even epic, failure. No country has yet succeeded in reversing weight trends. In fact, a recent study, published in The Lancet, found there are now more overweight than underweight people worldwide.

At the same time, the societal push to lose weight creates serious and emotionally damaging self-doubt, since people typically fail in their weight-loss efforts—and when people can’t lose weight, they are made to feel like failures. This phenomenon is easy to explain: Our current public health and biomedical approaches to obesity blame people’s lack of willpower and work ethic. So too does the massive, far-reaching diet industry. “The world hates fat people,” Mia’s mom told her more than 30 years ago. It’s even more true today.

Given the apparent ubiquity of this sense of failure, we expanded our research efforts to see if we could find safe spaces in which people felt good about themselves as they worked to lose weight, even if their weight-loss attempts “failed.” We proposed that online venues such as blogging might provide such a place, since bloggers theoretically have a great deal of control over how they present their bodies and stories. Our assumption was that bloggers would feel empowered around their weight-loss efforts, regardless of the outcome. We tracked 234 U.S.-based bloggers over the course of 2014 and 2015 and analyzed themes such as weight-loss success, weight-loss failure, and body acceptance.

It turns out that virtual worlds are often as miserable for people struggling with their weight as in-person realities. Blogs are riddled with expressions of failure, as people “confess” their lack of “discipline,” their incompetence at exerting “self-control,” and their inability to eat and exercise as they believe they should. Even worse, the small percentage of bloggers we studied who pursued nonconformist ways of thinking—such as embracing the health-at-every-size approach to self-acceptance—were subjected to vicious online troll attacks. People accused the women of immorality, telling them they should be ashamed of themselves and their bodies, and occasionally even threatening physical violence. When it comes to weight, online experiences, even in blogs—where the body is unseen—often mirror what happens offline.

Stigma related to weight affects every aspect of a person’s life—and the repercussions are serious and extensive. Weight perceived to be excessive cannot be hidden, and obesity is associated with a significant wage gap, fewer educational and career opportunities, and outright bullying in many countries, including the United States. Discrimination based on weight is technically illegal in the workplace under some interpretations of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, but this legal protection remains difficult to enforce. Even while two-thirds of people in countries such as the U.S., Mexico, and New Zealand are classified as overweight or obese according to the World Health Organization, there is no widespread political push to protect obese individuals from mistreatment.

But the harshest judgments often come from loved ones, as weight-stigmatizing comments are justified as part of efforts to protect or care for the obese family member’s health and well-being. Stigmas tend to be cruelest, and most personally and politically hard to shift, when they are seen as a person’s “fault.”

Bariatric surgeries like Mia’s and her mother’s do bring about pronounced weight loss and allow for a relative escape from everyday discrimination—depending on the amount of weight lost, the degree to which a person is able to maintain the weight-loss, and the amount of stigma individuals experience for choosing bariatric surgery. In her second and third interviews, both conducted post-surgery, Mia emphasized her “success” at weight loss, as well as the work she felt she had done to change her daily behaviors and food triggers, even when she was very ill post-surgery. Other patients responded to her in kind, focusing on her weight loss rather than her illness.

One day, for example, in the fall of 2015, when we were chatting casually with Mia at the hospital clinic, we ran into a young woman who was also a bariatric patient. Mia described to her the extensive post-op physical pain she had been dealing with, but then she pointed out that she had continued to lose weight: “I’m almost at my goal weight!” she said triumphantly. Although Mia appeared very drawn and tired, the other woman responded, “Yes, you look great! All the weight you’ve lost!” Both women had firmly shifted the conversation away from focusing on the pain and exhaustion that had been plaguing Mia.

Bariatric surgery and other radical weight-loss interventions are not a population-level “fix” for obesity—they are too expensive, too risky, and too inaccessible to most people around the world. They also rely on some of the same tropes around individual behavioral change (as we see in Mia’s description of the “work” she did to change her behavior). Most of the less-radical efforts, however, are doomed to fail: so says the overwhelming majority of the scientific evidence today. Studies show that while losing weight through exercise and dieting sometimes succeeds in the short term, it is typically followed by weight regain in the long term that often exceeds people’s pre-diet weights. Even many bariatric surgery patients regain weight over the long term, although not usually to their pre-surgery levels.

A myopic focus on forcing individuals to reduce their weight hasn’t worked—and it never will. Yet even as scientific research suggests that the solutions to widespread obesity lie in systemic fixes, not personal efforts, the latter continue to define national anti-obesity campaigns. Diet and exercise matter, but we need to live in communities where good food and physical activity are the default—not the result of a personal choice or effort.

To accomplish this, we need public investments in solutions aimed at addressing epidemiological increases in weight in a collective manner—like creating walkable cities (instead of expecting individuals to carve out money and time to go to a gym) and healthy food environments (instead of expecting individuals to eat a balanced diet while being inundated with messages to consume, consume, consume). Our belief that these changes need to happen is shared by thinkers from many fields—public health, urban ecology, geography, and so on—who argue that transformative shifts in the political and physical landscape are the only way to make livelihoods and lifestyles sustainable.

We also need to focus on improving health, not just on tackling weight. Scientific evidence shows, for example, that many people with “healthy weights” have diabetes and high cholesterol, and many others with technically obese bodies have perfect metabolic profiles.

The “problem” of obesity is that it is considered a problem at all, say many scholars. In this view, the solution is political action: giving voice to those who are stigmatized, empowering people to fight fat-hating norms, and pushing for acceptance of a range of body sizes. This is a vast and somewhat controversial cultural project. But what’s not controversial is the simple fact that fat stigma doesn’t make anyone’s life better. To combat fat stigma, we need to start with one small but very important step: We should initiate and support wide-reaching and more effective legislation to protect against weight-related discrimination. Fat shaming isn’t just morally wrong—it’s bad public policy.

In our interviews and online research, we hear and see the same phrase repeated again and again: I should have lost weight on my own. It has become the recurring motif of our research program. Our goal is to help write a new narrative, one that says we all need to be in this effort together.