Baby Fat Is About More Than Cuteness

“Aw, you still have your baby fat!” This refrain plagued me throughout my childhood. No matter what I did, I couldn’t shake my “baby fat.” I was not a particularly overweight child. I just seemed to maintain the round cheeks and pudgy tummy that most of my friends shed early on. “Oh, sweetheart, don’t worry,” my mother would say, “it will keep you warm. Just a little added insulation.” She wasn’t even half right.

In the years since, I’ve become an anthropologist who studies nutrition, human growth, and development. And, as it turns out, I wasn’t the only one who carried a few extra pounds. Humans are the fattest species on record at birth. A baby human is born with about 15 percent body fat—a higher percentage than any other species in the world. Only a small number of other mammals make it into the double digits at birth: about 11 percent for guinea pigs and around 10 percent for harp seals, for example. Even our nearest primate relatives are not born as fat as we are.

Most of the fat animal babies we think of—seal pups, piglets, and puppies—gain much of their fat after birth. This is true for all of our fellow mammals, whether they are much smaller than us or much larger. But human babies keep on gaining fat too. Infant fatness peaks between 4 and 9 months of age at about 25 percent before it begins a long slow decline. This period of baby fat thinning leads to a stage in childhood when most humans have the lowest body fat percentage they will have in their lives, unless of course you’re one of the not-so-lucky ones. So just why is it that human babies are born with so much fat?

Like my mom, many scholars have proposed that a thick layer of fat helps keep babies warm. But there isn’t much evidence that supports this theory. We don’t observe greater levels of body fat in populations that live in colder climates, and putting on layers of fat doesn’t seem to help us deal with the cold. Fat is critical to our warmth—it just doesn’t serve us by working only as insulation.

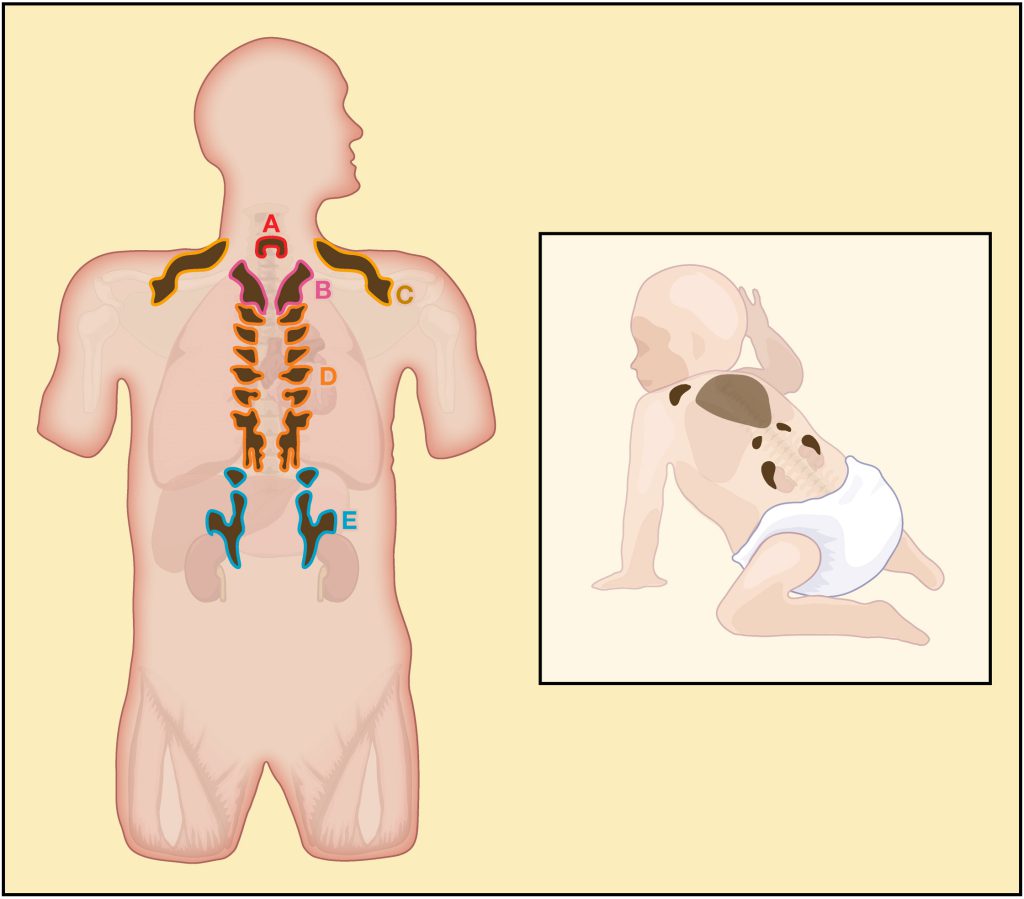

There are actually two kinds of fat: white fat, the normal fat we all know and love, and brown fat, also known as “brown adipose tissue,” or BAT. BAT is a special kind of fat that’s present in all neonatal mammals and is especially important in humans, who are unable to raise their body temperature through shivering. BAT generates heat by burning white fat and serves as a baby’s internal “furnace.” As infants and children develop, BAT begins to shrink until there is very little left in adulthood. Unfortunately for my mom, BAT only composes about 5 percent of an infant’s total body fat.

So, if it’s not for warmth, what does all that baby fat do?

Fat is the way that humans and all other mammals store energy. We do this to provide for ourselves during periods of nutritional shortfall, when there isn’t enough food or when food sources are irregular. One of the reasons such stores are so important for humans is that we have an extremely demanding organ that requires a lot of energy: our brain.

A human baby’s brain is massive relative to its body size and is estimated to use around 50 to 60 percent of a baby’s energy budget. That means if there are any shortfalls in energy or if an infant’s nutrition is poor, there can be serious consequences. As such, babies have large energetic reserves in the form of fat deposits that they can use if nutrition is inadequate. High fat at birth is particularly useful for humans, who go through a sort of fasting period after birth while waiting for their mother’s breast milk to come in; the first milk, or colostrum, is packed with protein, vitamins, minerals, and immune boosting antibodies but is lower in sugar and fat content than regular breast milk.

On top of needing to provide for their big, energetically expensive brains, human babies also require energy for growth and for staving off illness. As I mentioned, they continue to grow their fat reserves through the first 4 to 9 months of postnatal life. Interestingly, it is at this stage in their development that infants begin to experience two major issues: an increase in exposures to pathogens that can make them sick—crawling around on the ground, putting literally everything in their mouths—and marginal nutrition. During this phase, the nutrition that mom provides through breastfeeding isn’t enough and has to be supplemented with specially prepared, nutritionally dense foods.

While some of us can now acquire manufactured baby foods designed to do just that, such shortcuts weren’t available for the majority of human history. Between increasingly complex nutritional needs and the demand for energy necessary to fight off illness, human babies use their baby fat reserves as an essential energetic buffer for these transition periods, allowing them to feed their brains and continue their growth.

So my pudgy tummy didn’t offer warmth, but I guess my mom was right about one thing: Baby fat isn’t so bad after all.

This article was republished at Slate.