A New Generation Is Reviving Indigenous Tattooing

To celebrate her graduation from the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Alaska Native Studies program in 2012, Marjorie Kunaq Tahbone got a tattoo. Tahbone is Inupiat, an Alaska Native people, and the design was a traditional Inupiat pattern: three solid lines that spread downward from underneath the middle of her lower lip to her chin.

Tahbone was unsure, however, how the people in her home village would react. Nome is a town of about 3,800 people on Alaska’s northwestern coast, only reachable by plane or, in the warmer months, boat. Although many people there are Alaska Natives, traditional tattoos were a rare sight at that time.

Within days of receiving her tattoo, people started to notice. In a local store, a village elder reached out and touched her tattoo. In the weeks to follow, on two different occasions, babies, whom Tahbone was holding and playing with, fingered the pattern on Tahbone’s face.

The infants’ actions had profound resonance. Among Inupiat communities, babies receive the names of the recently deceased. When the infants touched her tattoo, Tahbone felt they were tapped into the memories of the past lives of deceased Inupiat. “When I was acknowledged by babies, it was like an acknowledgment of my ancestors,” she says.

Traditionally, chin tattoos among Inupiat women like Tahbone represented a number of different milestones, such as marriage, overcoming trauma, having kids, or, as in Tahbone’s case, a “coming of age.” According to anthropologist Lars Krutak, a research associate at the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico, tattoos were closely tied up in the cultural identity of many Indigenous people. “You could tell a lot about where that person was from, what clan they belonged to, maybe what family they belonged to,” he says.

Thanks to people like Tahbone, herself a scholar and tattoo artist, traditional tattoos are reappearing in Arctic and Northwest Coast Indigenous communities. As she and a handful of other researchers study and revitalize these lost arts, they are both reviving a cultural artform nearly wiped out by colonialism and getting a better understanding of the ways Indigenous communities in the north used tattoos. A tradition that once served as therapy for body and mind might now, in its restoration, treat deep cultural wounds. “When we see that ink on people, we know that we are healing from the historical trauma that occurred,” Tahbone says.

Tattooing in the north can vary widely, though there are a few common themes among the designs. Straight lines and dots around joints or banded around limbs are common, as are simple geometric shapes. Some tattoo designs are more ornate, with animal motifs similar to those seen on totem poles or other carvings on the Northwest Coast, representing whales, eagles, and other local species.

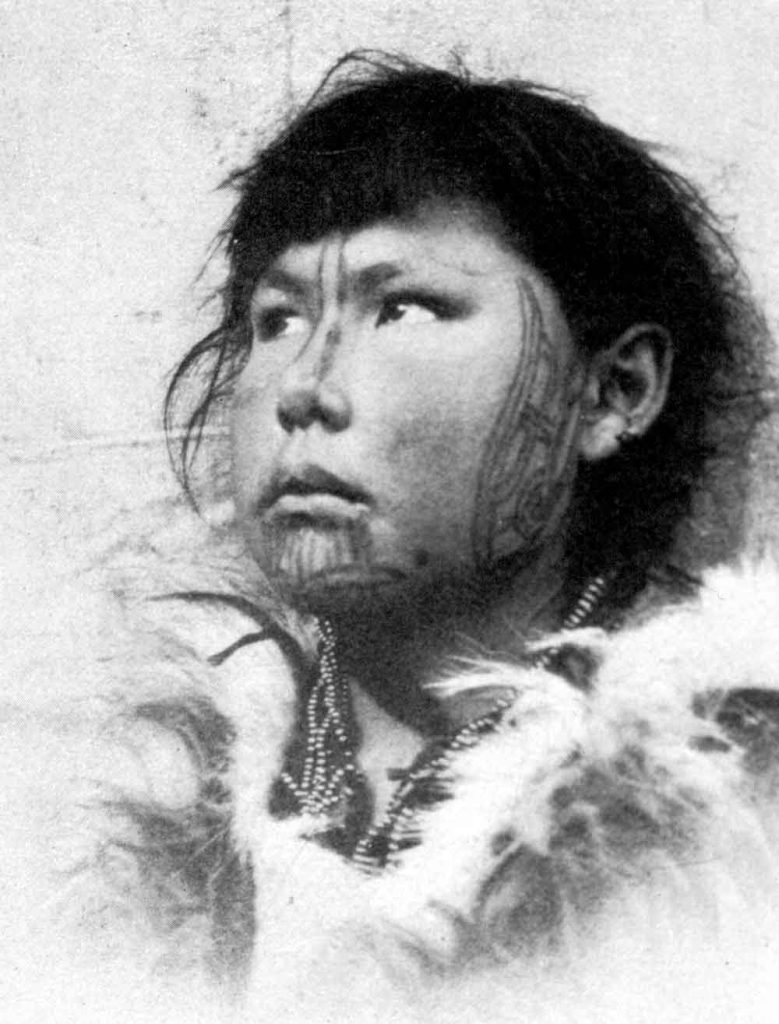

No one knows precisely how old the tattooing traditions of the Arctic and Northwest Coast are. They predate written history and stretch back at least 3,600 years, the rough age of an ivory mask of a heavily tattooed woman found on Devon Island, Nunavut, in 1986.

What’s better understood is how these traditions were very nearly erased. From the early 1900s to the 1970s, the U.S. government forcibly took generations of children from small communities in Alaska and sent them to boarding schools run by churches, the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs, and later, the Alaska state government. These schools aimed to convert American Indians to Christianity and force children to assimilate to a Western way of life. In Canada, parallel processes occurred in the government-sponsored residential school system, which removed Indigenous children from their families and attempted to erase their traditions and cultures.

Many of these children suffered mental, physical, and sexual abuse; some died during the process. The experience was deeply traumatizing for these Indigenous cultures. The loss of languages, ways of life, and cultural identity have had repercussions in Indigenous communities to this day. The art of tattooing was one of the era’s casualties, and the practice largely disappeared in northern cultures during the early 20th century.

But recently, anthropologists and a younger generation keen on reviving its cultural roots have been digging into archaeological and historical resources in an effort to learn more about the practice. Krutak has studied traditional tattoos around the world for more than two decades. In the mid-1990s, while working on his master’s thesis among the Yupik on Alaska’s St. Lawrence Island, he discovered about a dozen women in their 80s and 90s who still had traditional tattoos, inked in the 1920s.

A century of indoctrination from missionaries and boarding schools had taught these women and their communities that such practices were abhorrent. As a result, most people—with the exception of a few elders—were reluctant to talk about them. “It was very difficult to piece together enough information about how this worked,” he says. (In Nome, Tahbone has encountered a similar reticence among her village elders.)

The last of the women Krutak worked with died in 2004. He did more research over the years, looking through archives, old notes, photos, and even examining the tattoos carved into wood or ivory by northern people. He discovered, in his search, that the tattoos were much more than decorative body art.

On St. Lawrence Island, Krutak learned, people tattooed the joints of pallbearers after funerals and of hunters after they made their first kill of a bowhead whale, walrus, seal, or polar bear. Such tattoos were in part intended to stop the disembodied spirits of the recently deceased from entering the bodies of the living. The St. Lawrence Yupik believe that joints are vulnerable points in which malevolent spirits can enter and cause injury or arthritis to different body parts.

Krutak found that tattoos on St. Lawrence Island also had a therapeutic purpose—as do many other ancient tattoo traditions. For example, researchers have noted that some of the tattoos found on Ötzi the Iceman, the 5,300-year-old glacial mummy discovered in the Alps in 1991, correspond to traditional acupuncture points, which may indicate a wider health care practice at the time. Another case comes from a 2,500-year-old Siberian mummy with tattoos dotted on the lower back and spinal column—similar locations to some of the markings on the Iceman. Krutak observed similar tattoo placement on some of the women on St. Lawrence Island. “One woman told me straight up that they had a form of [tattoo] acupuncture they practiced,” he says.

Tattoos on St. Lawrence Island had a therapeutic purpose—as do many other ancient tattoo traditions.

Krutak believes these tattoo therapies likely developed independently through trial and error. “[People on St. Lawrence Island] just started tattooing joints because it worked,” he says.

The inks themselves may have also had therapeutic significance. Arctic people used pigments from plants with medicinal properties as well as soot taken from the bottom of lamps and charcoal. Activated charcoal is still used in modern medicine. Krutak says that these carbon-based materials could have helped with some joint injuries: “Soot has antimicrobial properties, and charcoal attracts bacterial particles to its surfaces and then they release out through the body.” Other pigments included graphite, which was sometimes available to St. Lawrence Island peoples through trade with Siberia. Some Indigenous people believed graphite could repel evil spirits.

Tahbone, meanwhile, has learned firsthand that the methods of tattooing can be therapeutic. Like Krutak, she analyzes photos, old documents, and other historical sources as part of her current master’s research on understanding the traditional ceremonies and uses of tattooing.

In 2016, Tahbone began studying the craft of making traditional tattoos with Elle Festin, a Filipino tattoo artist who wanted to revitalize traditional techniques. After receiving the blessing of a few village elders, she learned hand poking, which involves holding a tattoo needle dipped in ink and inserting it in the skin to create the patterns, and skin stitching, or pushing a needle with inked thread underneath the skin, going in at one point and emerging at another.

In skin stitching, the ink rises up in the skin to create a solid dark line. Using historic literature and the residual knowledge among her people, Tahbone learned that in Inupiat beliefs, the needle opens a vulnerable point in the skin from which negative energy can exit.

“The work of the tattooist and the energy that’s being put into the person counted as a therapeutic component of the tattoo,” Tahbone says. “The healer, the person tattooing, is transferring positive energy and releasing the negative energy with this tattoo work that they’re doing,” she says.

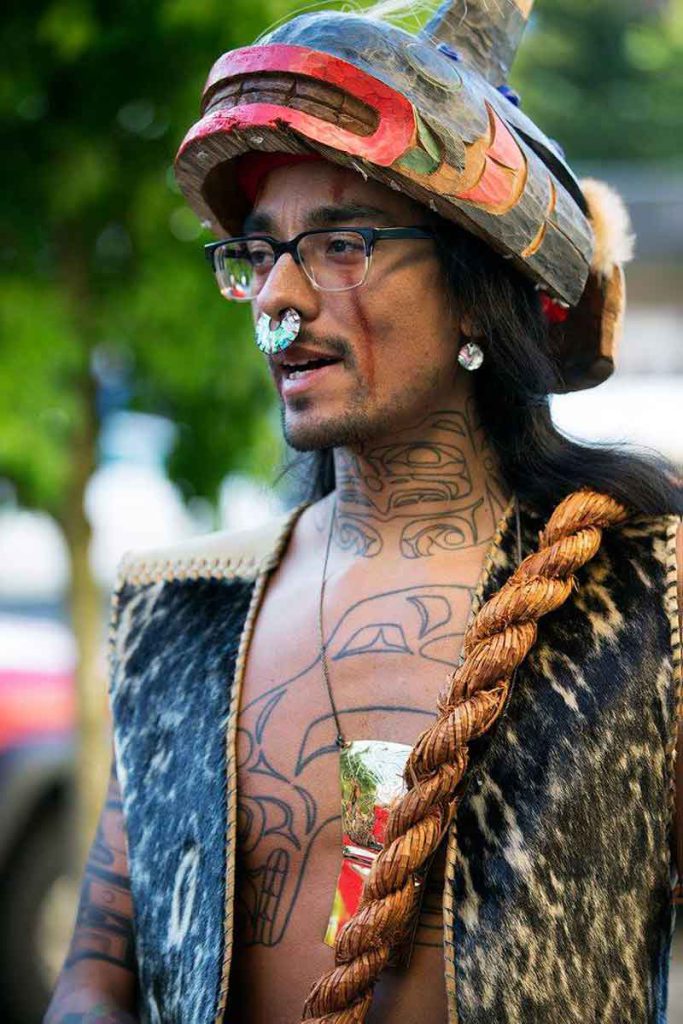

The Inupiat are not alone in their contemporary belief that receiving a tattoo can bring healing. On the Northwest Coast in British Columbia and Southeast Alaska, another Indigenous people, the Tlingit, have a similar association. Nahaan, a 36-year-old Tlingit-Inupiaq-Paiute tattoo artist who goes by the single name, says that part of the process puts people into an altered state of consciousness that contributes to long-term healing. “I sing a song for everybody before I start tattooing, and sometimes there’ll be stories along the way,” he says.

Nahaan has tattooed people in search of all kinds of help, including those who have suffered from a variety of traumas. “It allows somebody a doorway to open up and address the issues,” he says. Some clients even cry, he notes, not from pain related to the needles but because of the emotional issues they are working through. Traditional face tattoos, he says, can provide a deep sense of healing, since they help to restore pre-contact identity.

“I tattooed a lot of faces. Most of the time, they are these powerful Indigenous women, and they are stepping forward and saying, ‘This is what I want the world to think of me,’” Nahaan says, adding that they also want to show their ancestors that they remember the tradition through the generations.

Nahaan says that when he first started in 2009, no one else claimed to solely focus on Northwest Coast Indigenous styles and techniques. Now his Instagram is filled with tattoo artists from various Northwest Coast cultures, such as the Haida, Salish, Nisga’a, and Heiltsuk, among others.

“It took this younger generation, this younger internet generation, to pick up the mantle of tattooing and bring it back,” Krutak says.

The revival of tattoo artistry—though still, says Nahaan, in its early stages—offers its own form of healing. For both Nahaan and Tahbone, the work takes back elements of their culture being appropriated by tattoo artists all over the world. While there were only about a dozen Inupiat women with face tattoos when Tahbone got hers, now dozens more have this type of ink—and many more have other traditional tattoos, she says. “This is really an exciting time for our people because we are finally feeling like we can reclaim who we are again, and we can thrive as Indigenous people of the Arctic,” Tahbone says.

In communities where colonial schools and missionaries once attempted to eliminate Indigenous cultural practices, traditional tattoos suggest a powerful return of these practices, which may be as permanent as the ink itself. One woman to whom Nahaan gave a face tattoo told him afterward that she felt the piece had always been there.

Correction: March 13, 2019

An earlier version of the article implied that on St. Lawrence Island, people tattooed joints to prevent killed spirits from entering the body, rather than preventing the spirits of the deceased from entering the body.