Doctors Are Taught to Lie About Race

Doctors lie daily.

The moment a patient enters our care, a simple checkbox starts the deceit. By checking “Patient’s Race,” we health care providers pretend to know something that we cannot possibly know: the patient’s ancestry and associated medical risk.

While studying to become a physician, I was one of the lucky few who had the chance to also study human genetic evolution and its impact on health—topics missing from most medical curricula but central to fields such as biological anthropology.

I was struck by an alarming dichotomy: Genetics and anthropology scholarship have unanimously refuted a biological basis for race. These fields understood that racial categories used today in the U.S. were not the result of scientific investigation. Rather, they were invented centuries ago as part of a violent European system that colonized and enslaved non-Europeans.

Yet, the M.D. coursework, clinical training, and even medical literature reinforce the antiquated notion of sorting patients according to skin tone, that is, as Black, White, or another loosely defined racial category. When it comes to race, the U.S. medical system has fallen decades behind the rest of science.

By perpetuating unscientific racial sorting, medical professionals are failing patients—and medicine’s oath to “do no harm.” When we use racial categories to evaluate, assess, and treat patients differently, we mask the real reasons why medical outcomes vary among racial groups: No patient ever became ill because of the biology of their “race.” It was the impact of racism all along.

THE MYTH OF BIOLOGICAL RACE IN MEDICINE

During medical school, mentored by two experts in biomedical informatics and evolutionary medicine, I buried myself in scholarship generally absent from medical school: how the evolutionary pressures that shaped humanity contribute to modern disease patterns. I learned about the impact of viruses on the human genome and spoke at conferences about how our evolutionary past made us subject to diseases in modern environments.

Fundamental to this work is an understanding that, genetically speaking, human races do not exist.

The very notion that one could segregate people into groups that roughly approximate ancestry assumes those ancestral groups have remained separate throughout history. For many people subjected to “Black and White” racial sorting in the U.S., that historical proposition is false: Their ancestry crosses continental boundaries, sometimes at multiple points over centuries.

Beyond all of this, even the hypothetical ability to identify patients with predominantly recent African ancestry would not indicate disease risk based on genetics. The reason lies deep in human history.

THE DIVERSITY OF AFRICAN ANCESTRY

Homo sapiens arose in Africa roughly 300,000 years ago. Groups leading to most present-day people outside of Africa only began their global spread around 60,000 years ago. Humanity, for most of its existence, lived and died in Africa.

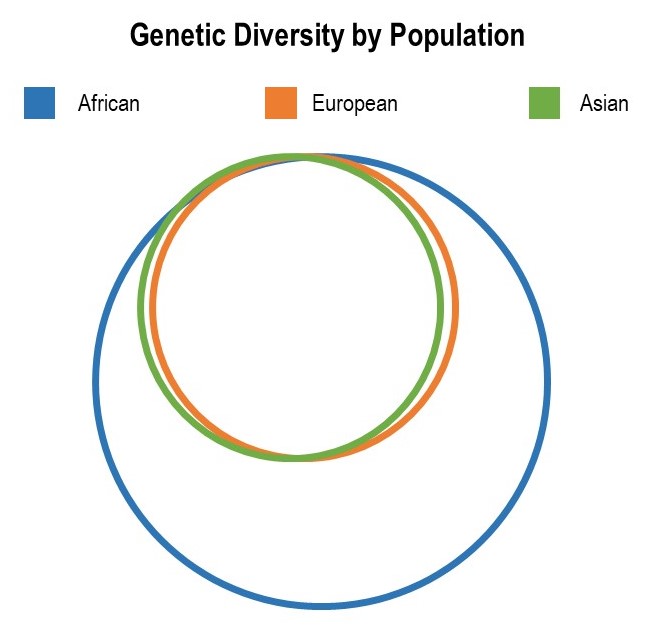

Outside of Africa, all the human haplogroups—clusters of shared genetic variations inherited from shared ancestors—descend from African haplogroups, a finding we would expect because humanity arose in the continent. All the haplogroups outside Africa descend from just one of the multiple haplogroups inside Africa, a testament to the dramatic reduction in genetic diversity that occurred when people spread out of Africa. (It is haplogroup L3, in case you want to impress friends with genetics trivia at a party.)

Today genetic diversity within those who live in Africa continues to measurably exceed the genetic diversity of people outside Africa across half a dozen metrics of variability.

These data lead to a conclusion that would undoubtedly surprise many physicians: There are fewer genetic differences between a European and an Asian patient than there are between two randomly selected people of recent African ancestry. It is less appropriate to generalize about the genetic makeup—and resulting health risks—shared by two African-descent patients than it would be for shared risks between an Asian and a European patient.

In a special case, ancestry does signal elevated health risks: groups with extremely reduced genetic diversity. People in these populations may descend from a small initial group of ancestors and/or mainly reproduce with fellow members of an insular community. Well-studied examples of such genetic isolation include Ashkenazi Jews and some populations in South Asia where in-group marriage prevails. Because in these cases parents are more likely to share rare genetic disorders, ancestry is indeed predictive of certain diseases and conditions, such as Tay-Sachs disease among Ashkenazi Jews or butyrylcholinesterase deficiency in the Vysya community of South Asia.

But this predictive power does not apply to broad African ancestry, the most diverse gene pool.

SOCIALLY DETERMINED DISPARITIES

Being labeled Black does not reliably indicate African ancestry, and African ancestry is too diverse to indicate shared genetic disease risk. And yet in the U.S., more Black people die early from treatable conditions and suffer from chronic diseases, including diabetes and heart disease, compared to White people.

Researchers outside of the medical practice understand why. The consensus among biological anthropologists and public health scientists recognizes that racism drives these inequalities rather than imagined race-related genetic differences. As a leading professional group of biological anthropologists put it:

While race does not accurately represent the patterns of human biological diversity, an abundance of scientific research demonstrates that racism, prejudice against someone because of their race and a belief in the inherent superiority and inferiority of different racial groups, affects our biology, health, and well-being.

Scientists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have linked health inequalities to non-biological factors—the so-called social determinates of health—including health care, education, economic stability, and environmental exposures.

At the same time, doctors, nurses, and other medical professionals carry false beliefs that worsen racial health disparities. In a now-famous study published in 2016, about half of the medical students and residents involved reported a range of biologically false beliefs about racial differences in patients, such as “Blacks’ skin is thicker than Whites.”

While many providers would never consider themselves to harbor racist intent, it is the presumed innocence and assumed scientific origin of these beliefs that makes them so dangerous to patients. Black patients literally pay the price for the pseudoscience of racialized medicine when their pain is ignored or undertreated: In the study, the medical providers endorsing racially biased beliefs recommended insufficient pain treatment for Black patients’ injuries.

These beliefs contribute to the disturbing fact that Black pregnant people are more likely to die from complications during pregnancy and childbirth—despite the absence of any genetic basis for risk differences. In 2021, for every 100,000 live births, nearly 70 Black mothers died compared to about 27 White mothers. In part, this is because health care providers often treat Black pregnant people differently—monitoring them less frequently and dismissing their symptoms.

The risks extend to world-class athletes and Black women wealthier than any hospital CEO. In a medical system ruled by racism, even Serena Williams and Beyoncé face risks that have no basis in biology.

SOCIAL SOLUTIONS

It’s time for medicine and society to acknowledge the actual drivers of health inequalities between the racial groups assigned by society. It’s time to call out the systemic racism.

Today, like every day, thousands of doctors will claim their patients’ race confers an elevated risk for a host of diseases, precludes certain medications and procedures, and more. Countless patients will think they inherited these risk factors because of their African ancestry.

Most patients and providers will have no idea that anthropologists and biologists have resoundingly refuted this notion for decades. Medical students, teachers, and practitioners must catch up with the rest of science: There is no clinical or genetic evidence of biological distinctions between racial groups, and it’s time for us to replace our outdated training with up-to-date information.

In practice, instead of lying to patients by blaming diseases on their unchangeable ancestry, medical professionals must learn to recognize the impacts of racism—and contribute to social solutions to this societal ill.

Our patients deserve better. While some medical boards have begun to endorse discarding racialized medicine, change cannot happen fast enough: We owe it to our patients to correct ourselves and our profession.

And if all else fails, the population we treat has the right to correct the medical profession the way every other institutional arm of racism has been corrected—from lenders who denied mortgages to realtors who wouldn’t sell to certain families in certain neighborhoods—via direct legislative intervention. If the medical profession can’t catch up to the science and get on board with equality, the public can pressure us to accept that necessary and urgent change.