Lessons From Lucy

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished under Creative Commons.

On November 24, 1974, on a survey in Hadar in the remote badlands of Ethiopia, U.S. paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson and graduate student Tom Gray found a piece of an elbow joint jutting from the dirt in a gully. It proved to be the first of 47 bones of a single individual—an early human ancestor who Johanson nicknamed “Lucy.” Their discovery of her would overturn what scientists thought they knew about the evolution of our own lineage.

Lucy was a member of the species Australopithecus afarensis, an extinct hominin—a group that includes humans and our fossil relatives. Australopithecus afarensis lived from 3.8 million years ago to 2.9 million years ago in the region that is now Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania. Dated to 3.2 million years ago, Lucy was the oldest and most complete human ancestor ever found at the time of her discovery.

Two features set humans apart from all other primates: big brains and standing and walking on two legs instead of four. Prior to Lucy’s discovery, scientists thought that our large brains must have evolved first because all known human fossils at the time already had large brains. But Lucy stood on two feet and had a small brain, not much larger than that of a chimpanzee.

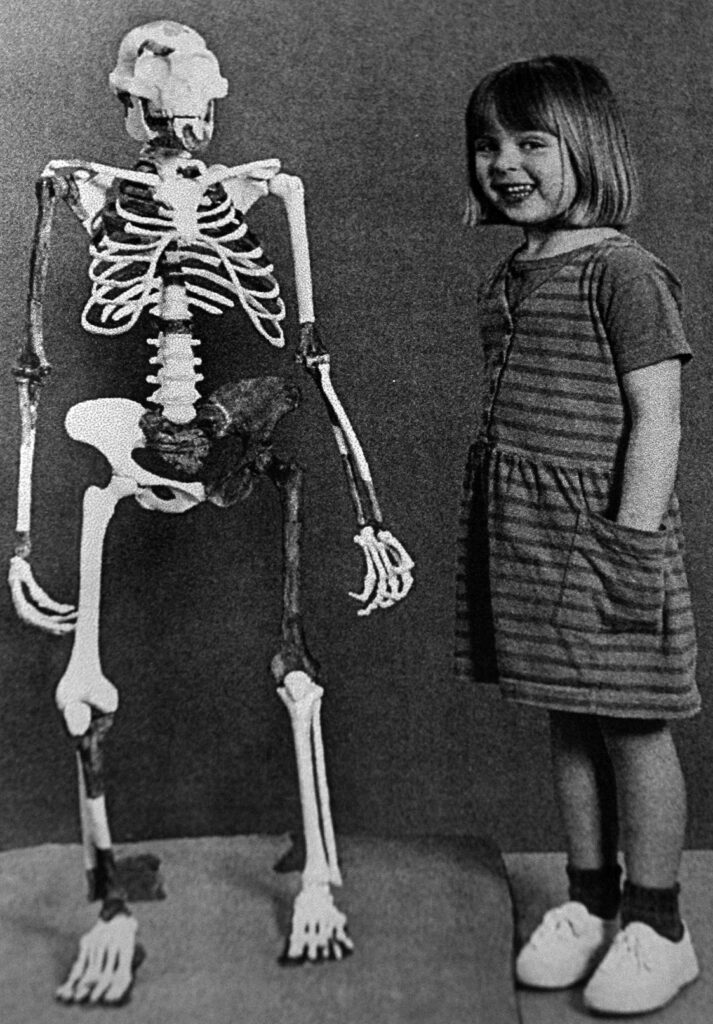

This was immediately clear when scientists reconstructed her skeleton in Cleveland, Ohio. A photographer took a picture of 4-year-old Grace Latimer—who was visiting her father, Bruce Latimer, a member of the research team—standing next to Lucy. The two were roughly the same size, providing a simple illustration of Lucy’s small stature and brain. And Lucy was not a young child: Based on her teeth and bones, scientists estimated that she was fully adult when she died.

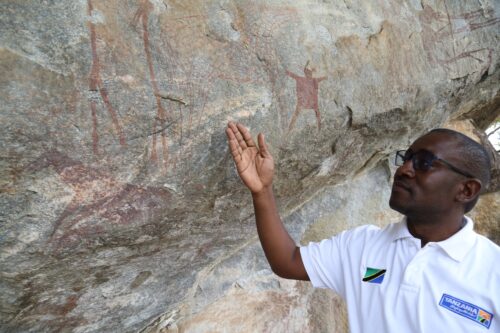

The photo also demonstrated how human Lucy was—especially her posture. Along with the 1978 discovery in Tanzania of fossilized footprint trails 3.6 million years old, made by members of her species, Lucy proved unequivocally that standing and walking upright was the first step in becoming human. In fact, large brains did not show up in our lineage until well over 1 million years after Lucy lived.

Lucy’s bones show adaptations that allow for upright posture and bipedal locomotion. In particular, her femur, or upper leg bone, is angled; her spine is S-curved; and her pelvis, or hip bone, is short and bowl-shaped.

These features can also be found in modern human skeletons. They allow us, as they enabled Lucy, to stand, walk, and run on two legs without falling over—even when balanced on one foot in mid-stride.

In the 50 years since Lucy’s discovery, her impact on scientists’ understanding of human origins has been immeasurable. She has inspired paleoanthropologists to survey unexplored areas, pose new hypotheses, and develop and use novel techniques and methodologies.

Even as new fossils are discovered, Lucy remains central to modern research on human origins. As an anthropologist and paleoecologist, I know that she is still the reference point for understanding the anatomy of early human ancestors and the evolution of our own bodies. Knowledge of the human fossil record and the evolution of our lineage have exponentially increased, building on the foundation of Lucy’s discovery.