Why Are There So Many Humans?

Something curious happened in human population history over the last 1 million years. First, our numbers fell to as low as 18,500, and our ancestors were more endangered than chimpanzees and gorillas. Then we bounced back to extraordinary levels, far surpassing the other great apes.

Today the total population of gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, and orangutans is estimated to be only around 500,000, according to the World Wildlife Fund. Many species are critically endangered. Meanwhile, the human population has surged to 7.7 billion. And the irony is: Our astonishing ability to multiply now threatens the long-term sustainability of many species, including ours.

What happened? Why do we live in the Anthropocene and not a world resembling Planet of the Apes? We share around 99 percent of our DNA with our great ape cousins, chimpanzees and bonobos. So, what makes us different from our closest relatives that gives us our staggering capacity for reproducing and surviving?

As an evolutionary anthropologist, these questions have led me to live and study among the Yucatec Maya of Mexico, the Pumé hunter-gatherers of Venezuela, and the Tanala agriculturalists of Madagascar. My research, combined with genetic data and other studies, offers clues to what developed in the deep past that has made humans so successful—for better or for worse. [1] [1] The author derived much of this essay from her 47th JAR Distinguished Lecture, “How There Got to Be So Many of Us,” which was published in the Winter 2019 issue of the Journal of Anthropological Research.

In the 1970s, the isolated village of Xculoc, in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, was home to about 300 Maya people. The maize-farming residents had no electricity or running water. Women hauled water from a 50-meter-deep well using ropes and buckets. They ground maize—the mainstay of their diet—in hand-cranked grinders.

Then two technologies were introduced that changed these Maya’s lives and, ultimately, their population: a gas-powered water pump and two gas-powered maize grinders.

Using these devices, young women saved about two and a half hours of labor and 325 calories a day. In addition, younger siblings could more easily fetch water and crush maize, freeing up their older sisters’ time and literally decreasing their daily grind. That’s important because studies have found that heavy subsistence work suppresses ovarian function, whereas reducing labor and raising women’s energy balance is associated with a bump in fertility.

Subsequently, the age at which women in Xculoc first gave birth dropped by two years. And according to my long-term research, women who started childbearing after these machines arrived produced significantly larger families than prior generations. By 2003, women who started reproducing in the 1970s had eight to 12 children.

Saving women time and energy is central to increasing the population. And humans have developed numerous technological and social ways of accomplishing this that differ from our great ape relatives.

It’s important to note that scientists must be cautious about drawing direct analogies between contemporary people or apes and our ancient ancestors. But modern humans and primates are our best tools for inferring how the underpinnings of our numerical success may have evolved.

Somewhere along the evolutionary road, humans started to favor new ways of having and raising their young. Mothers began weaning their infants earlier. In modern societies where infants rely on their mother’s milk and not bottle feeding, babies nurse for two to three years. By contrast, great ape mothers nurse their young for four to six years.

Breastfeeding is calorically expensive. It takes a mother about 600 extra calories a day to produce milk. So, the sooner she stops nursing, the sooner she can biologically support another pregnancy. In modern societies without contraception, mothers give birth on average every three years. Other great apes may wait as many as six to eight years between births.

Our ancient ancestors also fed, sheltered, and cared for youngsters who were weaned but still growing. This gave them a better chance at surviving than nonhuman great ape young, which fend for themselves after they’re weaned. Today a child living in a hunter-gatherer society is twice as likely as a wild chimpanzee to survive to age 15.

Novel ways of parenting, compared to earlier hominins, meant human mothers were in the unique situation of having multiple dependents of different ages to care for at the same time. I cannot underscore enough how much this sets human mothers and children apart from the other great apes.

Having lots of kids is great for the success of the species. But there’s a hitch. Mothers don’t have enough hours in the day to care for their babies full time while providing for their older offspring. That’s especially true because the unique aspects of the human diet give mothers a lot of tasks to juggle

When these ancient life history traits were evolving, our ancestors made their living as hunter-gatherers, who typically eat diverse fare, including fruits, nuts, tubers, roots, large and small game, birds, reptiles, eggs, insects, fish, and shellfish. Cobbling together such a menu requires modern hunter-gatherers to travel, on average, 13 kilometers per day. By contrast, chimpanzees and gorillas roam, on average, 2 kilometers per day.

Having lots of kids is great for the success of the human species. But there’s a hitch.

What’s more, hunter-gatherers process most of their food to make it more digestible or to boost the bioavailability of nutrients. And as everyone who prepares food knows, that takes a significant amount of time.

Among the Pumé hunter-gatherers from the savannas of Venezuela, women spend about three hours a day cracking, mashing, grinding, pounding, sifting, winnowing, butchering, and cooking food. The same is true of Efe women—hunter-gatherers living in the Ituri forest of Central Africa.

That prep time is in addition to the hours the Pumé and Efe spend foraging and then carrying ingredients back to camp. Furthermore, each processing task requires a specialized technology, which means someone has to collect raw materials and make tools. !Kung women and men in the Kalahari Desert of Southern Africa spend about an hour each day making and repairing tools. Savanna Pumé women devote nearly two hours to toolmaking—twice as much as the men.

Hunter-gatherers also build shelters and hearths to provide a safe place to process ingredients, to store food and tools, and to leave children who may be too young to accompany others on long foraging trips. Plus, they must haul water, chop firewood, fashion clothing, and maintain the social and information networks needed to access geographically dispersed resources.

There are simply not enough hours in the day for any one person to accomplish all this. So, our ancestors came up with a solution.

That solution was cooperation—but not the kind of task-sharing many species engage in. Hunter-gatherers developed a distinct feature called intergenerational cooperation: Parents help kids, and children help parents.

This is not a trait we share with the other great apes, who aren’t particularly good at sharing food, helping mothers or offspring who aren’t their own, or even supporting their own children after they reach a certain age. Nonhuman great ape mothers rarely share meals with their juvenile offspring once they’re weaned, and juvenile apes don’t offer food to their moms.

But among humans, intergenerational cooperation means it really does take a village to raise a child. Across cultures, mothers in hunter-gatherer and agricultural societies offer only about half of the direct care an infant receives. Savanna Pumé infants, for example, have an average of nine caretakers besides their mother. Efe infants have an average of 11.

Fathers and grandparents certainly play important roles in supporting their families. But it’s not enough. An average Maya mother is 60 by the time her last child leaves home, so she has very few years after that to be a babysitting or food-collecting grandmother.

My research suggests a much more obvious source of help has been overlooked: kids. Other than mothers, children provide most of the child care in many cultures. And 7- to 10-year-olds do the bulk of the babysitting.

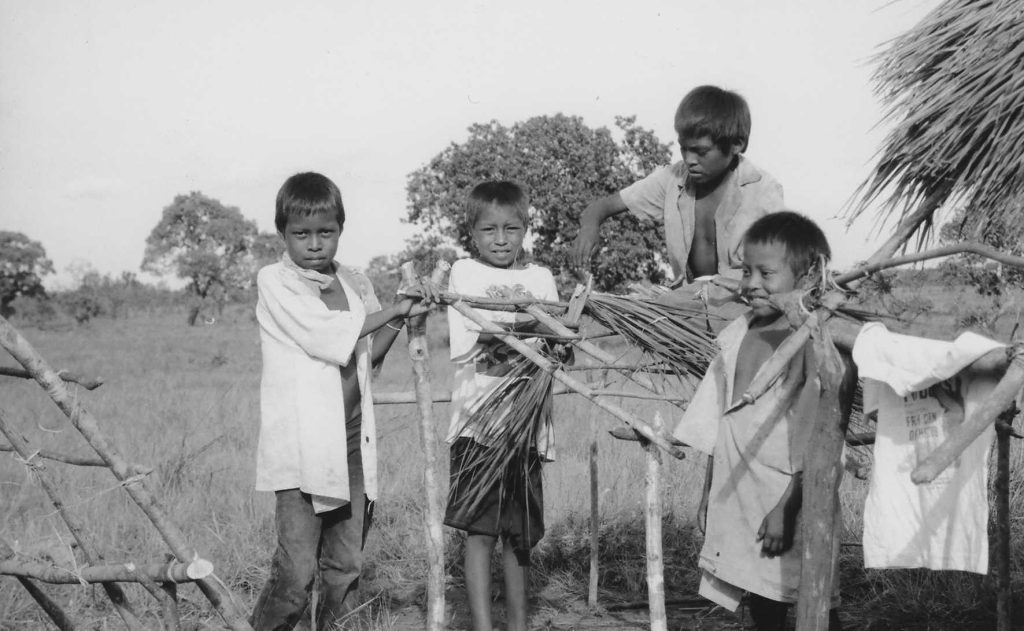

Children are also responsible for processing much of the food and running the household. A Pumé boy carries home an average of 4.5 kilograms of wild fruit on days he forages. That’s the equivalent of 3,200 calories—enough to feed himself and at least some of his family. (And that’s in addition to any snacking he does in the field.) His sister can bring home more than a kilogram of roots (worth about 4,000 calories)—some of which she will eat, but most of which she shares. Among the Hadza hunter-gatherers of East Africa, children forage for five to six hours a day. By age 5, they can supply about 50 percent of their own calories during some seasons.

Children in agricultural communities are also hard workers. Yucatec Maya between the ages of 7 and 14 devote two to five hours a day to domestic and field work. Teens between the ages of 15 and 18 labor about 6.5 hours a day—as much as their parents.

By the time a Maya mother is 40, she has an average of seven children at home. These children contribute a combined 20 hours of work a day and supply 60 percent of what the family consumes.

Thanks to this multigenerational help, a woman can spend time doing what only she can do: have more children. So, children increase the population, but their labor is also a built-in engine to fuel their community’s fertility and speed up reproduction.

With intergenerational cooperation and a diversity of dietary strategies, our ancestors multiplied and weathered population bottlenecks. Just after 1800, the human population hit 1 billion.

The global population then expanded exponentially, largely due to the enhanced survival of both infants and older people. It reached 2 billion in 1927, 3 billion in 1960, 4 billion in 1974, 5 billion in 1987, 6 billion in 1999, 7 billion in 2011, and today is at over 7.7 billion.

These figures intrigue me as an evolutionary enigma and deeply concern me as a contemporary issue. There is no question, though, that humans have been incredibly successful. The question is: How long can we maintain that success and still be sustainable? The answer, like our secret to growth in the past, stands on the shoulders of cooperation.