New Hominin Shakes the Family Tree—Again

This week, anthropologists working in the Philippines unveil new fossils that they say belong to a previously undiscovered species of human relatives. The fossils come from Callao Cave, on the northern island of Luzon, and are at least 50,000 years old.

The team, led by Florent Détroit of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris and Armand Mijares of the University of the Philippines, has named the new species Homo luzonensis after the island where it lived.

With only seven teeth, three foot bones, two finger bones, and a fragment of thigh, the set of Callao fossils doesn’t give much to go on. Their small size is reminiscent of Homo floresiensis, the tiny-bodied species discovered in 2003 on the island of Flores, Indonesia, that lived around the same time. But there aren’t enough remains here to say just how tall Homo luzonensis was. And, unfortunately, the team was unsuccessful in attempts to find DNA. Many people will wonder, on such slim evidence, if the declaration of a new species is warranted.

I was fortunate to be a part of the team that discovered the new hominin species Homo naledi, which lived in South Africa around 250,000 years ago. That work was published in 2015. Such discoveries seemed almost unimaginable 20 years ago, when I was finishing my Ph.D. At that time, some of the most respected anthropologists actually suggested that the hunt for hominin fossils was almost over. Funding agencies directed their efforts away from exploring for new fossils and toward new technologies to wring more precious data from fossils discovered in the past.

Yet the last 20 years have seen an unprecedented burst of new discoveries. Some, like H. naledi and H. floresiensis, represent branches of the human family tree that separated from the modern human line quite early and yet survived until a surprisingly recent time.

Was H. luzonensis another such population? To establish that these fragmentary fossils justify recognition as a new species, a key first step is to exclude their membership to modern humans. Living people of the Philippines include some very small-bodied groups. Small size alone is not enough to place the Callao fossil teeth outside the range of modern people.

To go further, Détroit and colleagues studied the details of the bones and teeth. Together, they represent a mash of features that are confusingly reminiscent of a huge range of other hominins, and together make for something new and hard to classify. The molars, for example, are small compared to every other known species, while the adjacent premolars, bizarrely, are not so small. The molar crowns have a simple, humanlike pattern, but the premolars bear resemblance to the larger teeth more typical in older species, including H. floresiensis and some early specimens of Homo erectus. Some premolars have three roots, as sometimes found in H. erectus and more distant human relatives. The toe and finger bones also seem different from modern humans: One finger bone is curved, and the toe doesn’t seem to have been able to bend upward at the ball of the foot as much as ours. In some ways, these bones resemble hominins that lived more than 2 million years ago, such as Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis. No other known species shares the whole set of features found at Callao.

So, what does this discovery mean? To me, it solidifies the case that ancient human relatives were a lot smarter and more adaptable than we used to give them credit for.

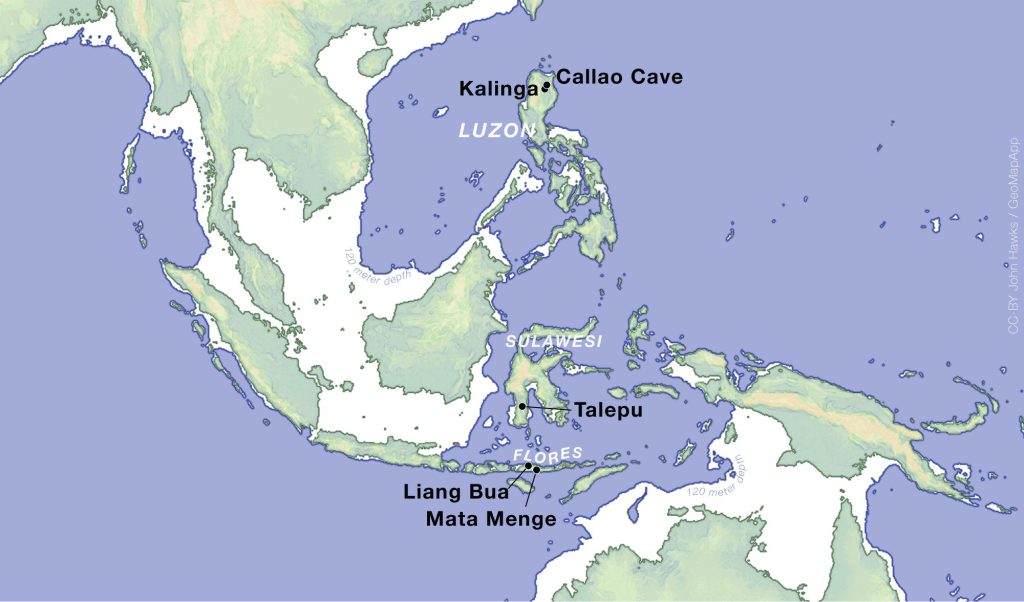

Flores lies about 2,000 miles to the south of Luzon, but both islands share a peculiar geography: Land bridges never connected these islands to the Asian continent. Another large, disconnected island in the region is Sulawesi. There, stone tools from a site called Talepu were made by hominins more than 118,000 years ago, though no fossils have been found yet to indicate who was making them. Some anthropologists have thought that the colonization of such islands over water was due to luck. Maybe ancient storms or tsunamis washed a few unsuspecting survivors onto ancient beaches. But where one strange event might be attributed to luck, three are much more interesting.

The evidence for life on these islands goes back a long way. Some hominins were making stone tools on Flores more than a million years ago, and the oldest hominin fossil on that island is around 700,000 years old. Last year, paleoarchaeologist Thomas Ingicco, from the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, and colleagues reported on work at the site of Kalinga, Luzon. There, they found stone tools and butchered rhinoceros bones, also around 700,000 years old. Very early forms of Homo must have surpassed barriers and found new ways of life in places with very different climates and plant and animal communities than their African ancestors. Meanwhile, within Africa, a diversity of hominin species continued to exist throughout most of the last million years.

It’s too early for us to say whether the earliest inhabitants of Flores and Luzon gave rise to H. floresiensis and H. luzonensis. I wouldn’t bet on it. Many new arrivals may have come between the first occupations and the later appearance of modern people in the region. One such arrival may have been the Denisovans, a mysterious group known from DNA evidence. Today’s people of the Philippines bear genetic traces of Denisovan ancestry, and new analyses of Denisovan genetic contribution in New Guinea suggest deep roots for this ancient group. Could the Denisovans have existed on Flores, Sulawesi, or the Philippines?

To answer such questions, we must reinvest in exploration. The new discoveries of the past decade or so have transformed the field of human origins. New methods of exploration, and more intensive exploration of underrepresented regions, have introduced a new paradigm. Ancient groups of human relatives were varied and adaptable. They sometimes mixed with one another, and that mixing gave rise to new evolutionary solutions. Our species today is the lone survivor of this complicated history. We have replaced or absorbed every other branch of our family tree.

Many more of these branches are surely waiting for us to find them.

Correction: April 16, 2019

An earlier version of this article stated that the team was led by Florent Détroit. Armand Mijares of the University of the Philippines led the dig; Détroit led the analysis. Both are corresponding authors for the Nature paper.