Can Rat Bones Solve an Island Mystery?

Please note that this article includes images of human remains.

When I ask her “So how big are the rats?,” E. Grace Veatch, a graduate student in zooarchaeology at Emory University, smiles and immediately holds her hands apart to show the body size of Papagomys armandvillei, the most common species of giant rat on the island of Flores in Indonesia. To my eyes, it is unreasonably large—about the size of a Jack Russell terrier or a raccoon. I mention this to Veatch. She nods, adding, “And that’s without the tail.”

Flores was once home to Homo floresiensis, a diminutive hominin species affectionately termed the “hobbit,” possibly as early as 700,000 years ago—although most of the finds are between 100,000 and 60,000 years old. H. floresiensis shared a common ancestor, likely Homo erectus, with modern humans. But populations of modern humans probably didn’t arrive on Flores before 46,000 years ago, and according to Veatch, archaeological evidence indicates that by then the H. floresiensis population no longer existed on the island.

What happened to the “hobbits”? Did their disappearance have something to do with the prey they hunted? How did modern humans hunt these animal species? Veatch is attempting to answer these questions by looking at the remains of prey species that both “hobbits” and modern humans consumed. She is particularly keen to understand the hunting strategies employed by H. floresiensis. How did hominins who only stood about 3 1/2 feet tall hunt giant rats and flying foxes (a large species of bat)?

Adaptation to island life tends to have some interesting effects on mammalian evolution. A combination of factors, especially the limited amount of food within the island’s barriers and the low number of large predators, promote dwarfism among mammals that would, in other environments, be much larger. Those same ecological forces have the opposite effect on smaller mammals—that is, these animals grow to much larger sizes than their mainland cousins. On Flores, for example, elephants became small (although this species eventually died out), while several species of rats became extremely large.

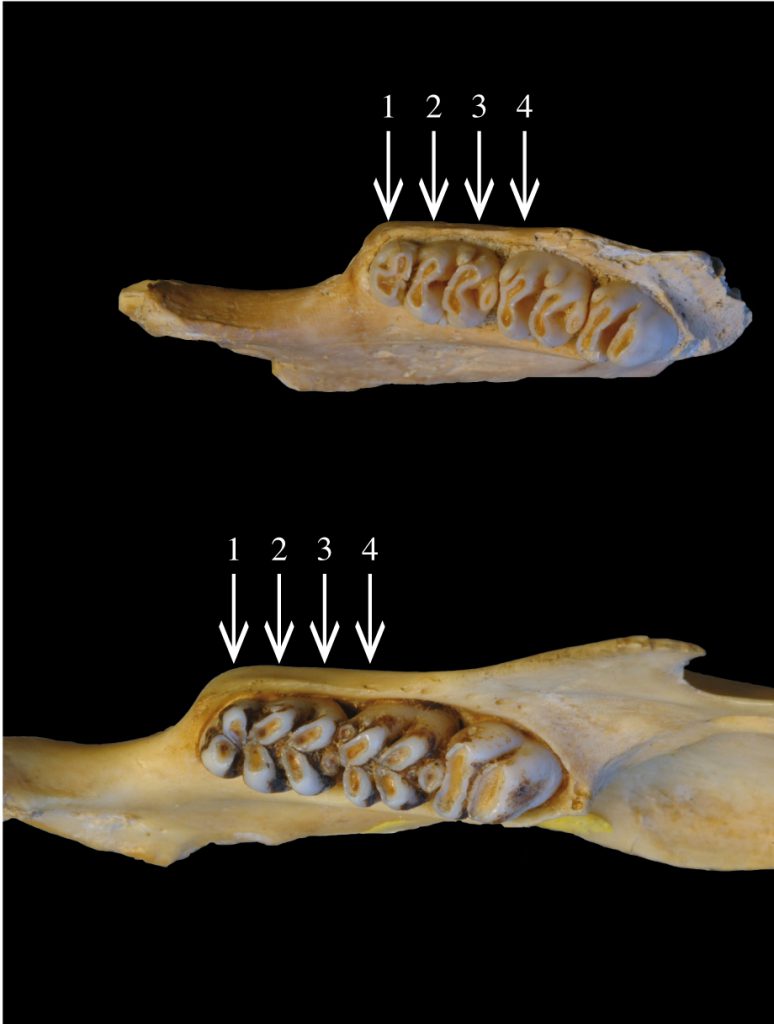

Veatch is studying the remains of several species of rat associated with H. floresiensis, and in later deposits, with anatomically modern humans at the cave site of Liang Bua on Flores. She has participated in excavations at the site since 2015 and has spent countless hours in the National Research and Development Centre for Archaeology (ARKENAS) in Jakarta, measuring the rat bones that are preserved in the archaeological material from the cave. So far, she has determined that at least five different size classes of rat existed in the area, ranging from small (the size of a city rat) to giant (those terrier-sized specimens)—as evidenced throughout the archaeological sequence.

By looking at the markings and textures, such as gouges or scrapes, on the surfaces of the rat bones, Veatch can tell whether the animal was butchered or whether it passed through the digestive tract of one of the local birds of prey. Most of the small- and medium-sized rats from Liang Bua seem to have been consumed by birds. However, Veatch was surprised to find some unexpected cut marks on one small specimen from the material associated with H. floresiensis. This introduced the possibility that the “hobbit” diet included all sizes of rat.

Her finding throws a bit of a wrench into the gears of an ongoing anthropological contradiction. Among anthropologists, there’s an incongruity in how evidence for small mammal hunting by ancient hominins is interpreted.

On one hand, when small mammal remains are found in archaeological sites, they tend to be associated with technological complexity—for example, the use of snares and nets. These tools require not only the skill to create the traps but also the forethought, environmental knowledge, and abstract thinking necessary for setting and checking them. These abilities are most often associated with anatomically modern humans.

On the other hand, when small mammal remains are found in sites associated with other members of the genus Homo, such as Neanderthals or “hobbits,” such evidence tends to be dismissed as showing that these rodents were diverse and plentiful—and therefore were “easy targets.” Those cut marks on the bone from a small-bodied rat, then, offer up the intriguing prospect that H. floresiensis occasionally incorporated the smallest rat species into their diet.

So what does a diet of small mammals really mean? Did H. floresiensis and Homo sapiens hunt these animals differently while living at Liang Bua? Did both populations use snares or traps to hunt? This puzzle is one that Veatch hopes to address with her research.

Answering these questions requires a number of different approaches—and not all of them take place in the lab. To create a collection of comparative examples of bird-digested bones, Veatch collaborated with Zoo Atlanta to feed rats to owl and vulture species similar to those found at Liang Bua and to collect the bones after they had been digested. Bird digestive systems haven’t changed much in the past few millennia, so the marks on the bones digested by the modern birds provide examples of what to look for on the ancient bones. “That’s been a really great resource,” Veatch says with enthusiasm.

To further uncover hunting patterns, Veatch plans to use stable isotope analyses of the rat remains to determine whether these Liang Bua rodents came from an open or closely forested environment, and at what altitude they lived. (Elevation is quite variable in the area surrounding the cave.) The mammalian body absorbs different ratios of the radioactive isotopes of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen as it consumes food and water throughout its lifespan, and the plant foods that the rats eat vary in their content of these elements, depending on where they grow.

So analyses of the ratios of these isotopes in the Liang Bua rat remains can tell Veatch if those rats came from the environment close to the cave or from farther afield.

She will then be able to determine how far H. floresiensis and H. sapiens typically traveled for their food.

Today, the inhabitants of Flores continue to make use of the island’s animal resources. Though the human population on Flores has significantly affected the fauna of the island, decimating many of the species that once lived there, rats and flying foxes still thrive and are prized as local food sources. Modern hunters who regularly kill the same rat and bat species as their very ancient ancestors might offer insights that can shed light on ancient hunting strategies. Veatch will return to Flores to observe modern hunting practices in collaboration with colleagues from ARKENAS, who will accompany and film the hunters. Veatch says she also plans to observe the butchering and cooking of the meat—and hopes to sample the final product.

Before I ended my conversation with Veatch, I asked her what the most important part of her work at Liang Bua was. She said she feels lucky to work with such an extraordinary team of researchers. And then, she added, there’s also that moment.

“One of the greatest feelings for me while doing this work has been the ‘aha’ moment. Every scientist knows the feeling, when you’ve discovered something for the first time,” she said. “While it’ll eventually be shared with the rest of the world, that moment is yours.”