The Shortcomings of Height in Politics

During Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ failed U.S. presidential campaign in 2023, his height garnered headlines. People speculated whether he wore lifts in his cowboy boots for an extra inch or so. Some shoemakers claimed the governor probably inserted boosters into his shoes.

Candidate and former president Donald Trump fanned the speculation, using his opponent’s stature as part of a “campaign of humiliation.” Reportedly, before Trump began calling DeSantis “DeSanctimonious,” he considered dubbing the governor “Tiny D,” another below-the-belt reference to his height.

That was not the first time Trump used height to ridicule his rivals. During the 2016 presidential primaries, he called 5-foot-10-inch candidate Marco Rubio “Little Marco.” In the runup to the 2020 presidential election, he described candidate “Mini” Mike Bloomberg as “a 5-foot-4 mass of dead energy” and falsely claimed the former New York City mayor requested a box to stand on during the presidential debates. Other politicians have received similar treatment from Trump: then-Sen. “Little” Ben Sasse, Rep. “Liddle’” Adam Schiff, and then-Sen. “Liddle’” Bob Corker (liddle’ being one of the Trump’s signature misspellings).

Trump’s 6-foot-3-inch stature has also been questioned, and a TIME journalist noted that “it irritates him that so many media outlets say 6-foot-2.”

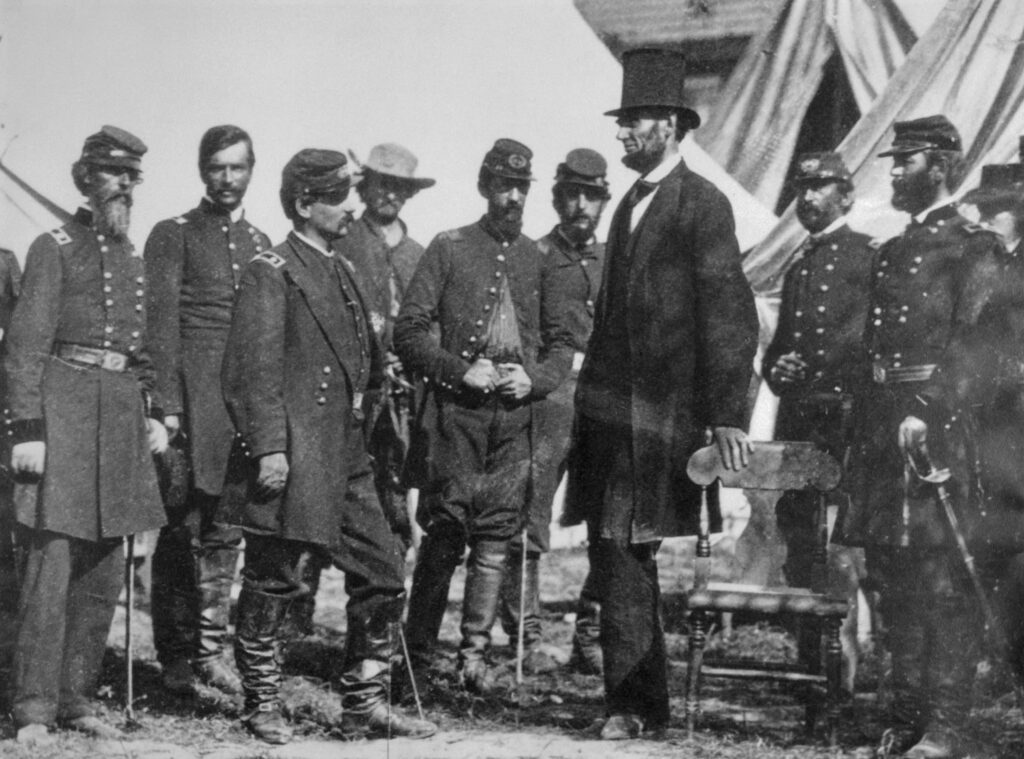

Although Trump is an extreme example, height has long been an issue in U.S. politics. Abraham Lincoln—who at 6-foot-4-inches was the tallest U.S. president—wore a top hat to appear even taller, according to historian Matthew Pinsker. “American voters usually prefer the taller man,” read a 1992 New York Times article devoted to Ross Perot being the shortest major presidential candidate in years. What can we learn from this preoccupation with height—that is, a few inches of difference—in U.S. politics?

THE BIOLOGY OF HEIGHT

As a medical anthropologist and scholar of human stature, for over a decade I have been studying how height figures into society. What makes height fascinating is that it varies from person to person, influenced by an interplay of factors but not determined by any single one.

Genetics, of course, plays a big role. Studies suggest genetics explains 80 percent of the differences in height that occur among people. But this inheritance is complex, with stature influenced by hundreds of genome variants—nearly 700 in one analysis. Whether a person actually reaches their height potential depends on many other variables, including childhood nutrition and diseases contracted during growth. The reason: Stressors such as illness can consume energy that would otherwise go to growth.

Consequently, height has been a long-standing preoccupation of pediatricians (hence, child growth charts), public health practitioners, and parents. Many see it as a measure of health and well-being—as well as an important outcome in its own right.

TALL ORDER

Beyond height as a biological attribute, it also carries social values and stereotypes, especially for men but also for women. These attitudes permeate the realms of sports, employment and earnings, fashion—and yes, politics.

Outside of the U.S., world leaders’ heights, too, have been scrutinized, including those of Russian President Vladimir Putin (does he wear heels?), North Korean leader Kim Jong Un (who Trump called “Little Rocket Man”), and British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak. “If not for Mr. Biden and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, the G-7 could well be renamed the 5’7”,” wrote a columnist for The Wall Street Journal in 2022. While men’s heights receive greater scrutiny, women are not spared—from Scotland’s Nicola Sturgeon to the Philippines’ Gloria Macapagal Arroyo.

Historically, we can go back to the French general-turned-emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, whose alleged short stature inspired the recent idea of the “Napoleon complex,” a popular belief that short people compensate for their height with attention-grabbing acts.

In an attempt to offer context, some reports on DeSantis’ height have cited the fact that U.S. presidents have been taller than average for U.S. males, including 6-foot-1-inch Barack Obama and 6-foot-2-inch George H.W. Bush. Others have echoed ideas from evolutionary psychology that suggest men’s preference for tallness stems from “an inherent desire to appear dominant and attractive to potential partners.”

But anthropologists and sociologists offer a broader view of height’s standing. Other researchers and I have found the value of height has varied across time and place. It is not a given that tallness confers economic or social benefits. Those outcomes depend on the culture and historical moment.

ESCAPING HEIGHTISM

The significance of height is best understood as intersecting with other aspects of inequality, including socioeconomic status, race, and gender.

For example, owing to various factors, including nutrition, access to health care, and socioeconomic inequalities, there is a strong association between height and household wealth, as well between height and income. In the late 19th century and into the 20th century, height served as a marker of perceived superiority between Americans and their colonial subjects, including Filipinos. And because tallness is also associated with masculinity, shorter-than-average men, such as soccer star Lionel Messi, have been represented as “weaker” and “subordinate.”

Accusing a male politician of wearing lifts not only “belittles” him (note how ideas on height are encoded in language), but also emasculates him based on toxic notions of masculinity.

Such discourses, especially when amplified in mass and social media, feed into preexisting discrimination toward people who are shorter. There have been efforts to curb this heightism. And at least one political leader—Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni—has won damages over her height being mocked. But many see height as a “natural” phenomenon, making it harder to challenge inequality tied to it.

We all—pundits, politicians, the public—should try to stifle the notion that tallness grants superiority and shortness is a shortcoming. By participating in a politics of diminution, we diminish our politics.