Untangling Race From Hair

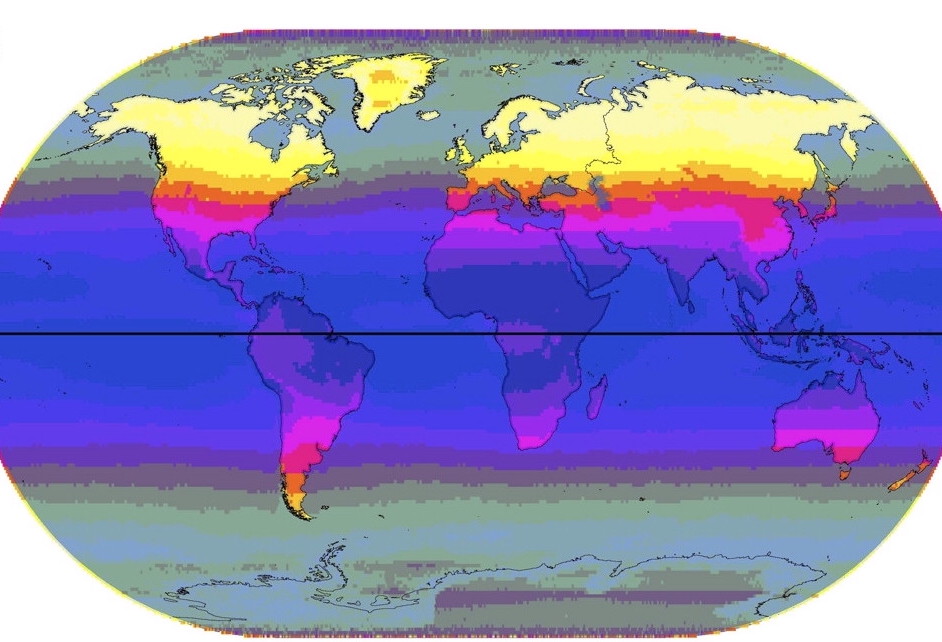

In an undergraduate biological anthropology class in 2011, Tina Lasisi heard a lesson about human skin tones that would change the course of her career. The professor displayed maps comparing the distributions of ultraviolet radiation and degrees of skin pigmentation around the world. Both overlapped almost perfectly.

“That was just very much a ‘eureka!’ moment for me,” says Lasisi, now a postdoctoral biological anthropology researcher at Pennsylvania State University.

Until then, Lasisi had never thought about skin pigmentation as a gradient, or how it came to be distributed, biologically and evolutionarily, around the world. Seeing pigmentation explained as a spectrum of variation that met the needs of survival—protection against harmful UV rays—was illuminating to Lasisi. It presented an evolutionary narrative to explain skin diversity beyond facile, arbitrary racial lines.

“And I’m thinking, OK, cool, that explains skin color and why I’m brown,” recalls Lasisi. “But what about hair?”

As a Black woman, Lasisi saw the parallels between skin and hair immediately. Both are highly racialized physical traits that are frequently stigmatized, especially in Western societies with white majority populations, where culture is still weighted by Eurocentric beauty standards. [1] [1] In this article, white is styled lowercase throughout, contrary to SAPIENS’ house style, at the request of the author. Black women often feel pressured to alter their hair, especially in settings and institutions that may deem their appearances “inappropriate” or “unprofessional,” like schools and workplaces. That stigma is even present in the language people use to discuss these traits: Dark and light have value connotations, and Black hair is often described with demeaning adjectives like “kinky,” “frizzy,” or “woolly.”

After that revelatory class, Lasisi went to her professor, to postdoctoral researchers, to anyone she could find, to ask about the evolution of hair diversity and why human hair looks and feels the way it does. Nobody had an answer. One postdoc took her under his wing and suggested, “Maybe this should be your undergraduate thesis.”

This set Lasisi down a research journey that has lasted more than a decade—a quest to find an empirically based, measurable metric to describe the evolutionary narrative of hair.

“It almost felt like a responsibility,” she says.

Many adjectives that describe very curly hair are derogatory, and not at all new. They’ve been used for at least the last two centuries, alongside other measures, to justify racial hierarchies and white supremacy. In the 1800s, naturalist Ernst Haeckel devised a taxonomic category of “wooly-haired” humans that included “bushy-haired” Papuans and “fleecy-haired” Africans. In apartheid-era South Africa, authorities developed a pencil test to determine someone’s race. They placed a pencil in a person’s hair, and if it stayed in place due to their tight curls, they were classified as “Native” (Black) or “Colored” on their identity documents and segregated accordingly.

Today the concept of race is recognized as not having any basis in biology but is entirely a cultural construct—one that has led to genocide, massacres, severe exploitation, and other human rights abuses. So, over the past 20 years, scientists and the public have been shifting toward more evidence-based and emotionally neutral language about skin tone and race.

While melanocytes, the cells that create melanin, were discovered in the 19th century, it wasn’t until the early 2000s that “melanin” and “melanated” widely made their way into colloquial, nonscientific use. The words were entered into the Urban Dictionary in 2005 and 2016, respectively.

“People rarely appreciate how incredible it is that that’s become part of our common vocabulary,” says Lasisi. Talking about skin tone in terms of melanation is powerful, she says, because it’s an observable, measurable quality that’s based in evidence.

For scientists, she adds, a melanin index is a more precise metric that can increase statistical power in analyses. Sweeping racial categories are homogenizing, a problem especially when you consider that race itself has no clear parameters. But having degrees of melanin—a scale with empirical and numerical backing—reveals hidden variation and gets closer to the truth.

After all, race is a social invention, and each racial category, the lines that differentiate between them, and the variation of traits that individuals within a race can possess are all nebulously defined. Plus, they vary depending on where you live. What people mean when they say “Black” or “white” can encompass a huge spectrum of skin tones. But those definitions have been carved out by predominantly white scholars who presented their own race with a wealth of nuance that they did not necessarily give to others.

Knowing the evolutionary advantage of melanin makes skin pigmentation something to celebrate rather than denigrate. “It comes paired with the knowledge that this was a trait that was selected for and that our ancestors needed in order to, you know, survive,” Lasisi says. “That’s a point of pride. But there isn’t an equivalent for hair.”

In her search for the roots of hair variation, Lasisi pored over the literature and found there are only a few papers over the past six decades that quantitatively look at hair diversity. What little research exists tends to look at growth rates or hair cross sections, and focuses mostly on Europeans.

One reason for the dearth of studies is that anthropologists shy away from researching skin color and hair, explains biological anthropologist Nina Jablonski—one of the biggest players in the field of skin pigmentation diversity, and one of the academics who researched those UV ray and skin tone maps.

Just as melanated skin protects against UV rays, tightly curled hairs also protect humans from the sun.

“People are very wary of studying and talking about these traits because they have been used to classify people into previously very rigid categories and hierarchical categories,” says Jablonski, who has served as Lasisi’s doctoral adviser and now postdoctoral adviser at Pennsylvania State University.

Anthropology has a complex history in which the discipline and some of its famous proponents helped create and disseminate racist ideologies based on pseudoscience. After World War II and the civil rights movement, the field wanted to jettison that reputation. But rather than actively restructure the discipline, Jablonski says, many researchers preferred (and still prefer) to not traverse what they see as an academic landmine. Some view skin and hair as aesthetic and therefore superficial subjects. Hair, especially, is often seen by researchers as purely decorative or ornamental.

But our skin and hair are how we interface with the world, says Jablonski. They are the physical parts of our bodies that interact with our environment and one another. They line the boundary between self and not-self. They are our most immediately visible traits, and therefore, among the first things humans judge each other on.

By including skin and hair in analyses of human evolution, Jablonski says, anthropologists can think about early humans as full people with “whole bodies moving through time and space … instead of these moving skeletons.”

“To not think about these things, to just dismiss them as being superficial,” Jablonski says, “is terribly unscientific, and really lamentable.”

When Lasisi began her research, she was essentially entering a void; science did not have an adequate framework or language for describing hair variation that stood apart from the racist history. She knew intuitively that the most obvious, racialized, and quantifiable quality of hair is hair curvature or straightness. But when searching for methodologies to measure that variable, she found cosmetology studies that assessed things like “frizziness” or “combability”—both metrics with clear bias baked into them. Few people want to describe their hair as “frizzy” or “uncombable.”

Hair stylists often define hair using Andre Walker’s Hair Typing System (created by Oprah Winfrey’s stylist), which designates hair types with a number and a letter. Numbers 1 through 4 represent straight, wavy, curly, and kinky, respectively; each is further subdivided by letters that describe different textures, such as fine and coarse. But this system is imprecise because it’s based on perception.

One of the few valuable papers Lasisi found is a 1973 study in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology. In it, Daniel Hrdy, of Harvard University, loosely described a methodology to quantify the shape of a hair curl, which he applied to seven groups of people around the world. Imperfect as it was, it was the starting point Lasisi was looking for. She built off his research, honing a methodology for fitting hair fibers to a circle to determine curvature and publishing her results in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology and Nature’s Scientific Reports.

Jablonski says Lasisi’s work suggests how, just as melanated skin protects against UV rays, tightly curled hairs also protect humans from the sun. Tight curls create lofted, airy ventilation structures for the head, allowing it to breathe while providing extra protection from solar radiation. That was important for our newly bipedal human ancestors, she says, and you can’t do that with flat hair.

Understanding quantitatively how evolution drove the diversity of hair gives people a lens to see the purpose and power of their appearance, says Lasisi. Furthermore, she adds, describing hair with an empirical, numerical metric reveals the diversity among Black people—the proof is literally in the numbers. It disproves those who would view Black people as a homogenous group and who erroneously portray European populations as more variable than others.

Read more about misconceptions in racial classification: “Race Is Real, But It’s Not Genetic”

But some people question how far new terminology and metrics can go toward untangling hair from its racialized history. After all, cultural narratives imbue people with implicit biases, leading people to make immediate assumptions about race and character—consciously or unconsciously.

“Once people understand the degree to which a person is dark, it really actually doesn’t matter what race a person is,” says Yesmar Oyarzun, an anthropology doctoral candidate at Rice University who studies how dermatologists learn to perceive skin disease in the context of race and diversity. In other words, if the context of your environment is one of anti-Blackness, then it doesn’t matter how you label different shades of Black skin or tightly curled hair, because that racism is still there.

Nevertheless, Oyarzun says she hopes Lasisi’s work inspires other researchers to focus on skin and hair conditions that more frequently impact people of color. Hair and skin color are still often used as proxies for race. And race, in turn, is often used to make assumptions about health and risk factors. Ignoring the science and diversity of skin and hair leaves space for those biases and potential health disparities to persist.

“When you don’t care about the problems of people with dark skin, you also don’t care about Black hair,” says Oyarzun. Hair loss, in particular, is a big reason Black women see dermatologists, she adds, and when it comes to disparities between white and Black women, “the conversation about hair morphology is actually painfully missing.” Oyarzun says Lasisi’s work could break open the black box of Black hair loss.

Lasisi is consistently baffled that this field has been left open and empty for so long, especially when she sees so many multidisciplinary research questions to pursue. For example, her work could be used for genome-wide association studies to investigate topics such as how hair curvature correlates to genes related to hair loss, or how genes that influence curvature impact other health metrics. This research could also help biomaterials scientists understand the biophysics of hair, which could lead to new synthetic materials, or even help animators realistically depict hair diversity.

Being able to generate knowledge, Lasisi adds, is a position of power, and she hopes to empower other researchers from all kinds of fields to join her in this work. “I have all these ideas, but it’s way more than I could ever do on my own,” she says. “And I wouldn’t want to do it on my own.”