Envisioning a More Empathetic Treatment of Great Ape Remains

HIS SKULL WAS FREE of visible trauma. No bullet holes. No caved-in fractures. Yet he had been shot eight times before he died, and his body was left to hang overnight in a tree.

I wasn’t shocked to learn of his brutal end. Such chilling deaths were commonplace in the 1800s. What surprised me was how well hidden his trauma had been. His skull, resting among countless others in a drawer, looked like any other specimen preserved for research. This observation left me unsettled and deeply reflective. What hidden traumas may have been endured by all the others now housed beside him?

I wondered if any people before me who utilized his remains for their research had ever pieced together his story—or even contemplated how he got to the Natural History Museum in London. In this case, researchers know how he came to rest in a drawer there: The orangutan was shot by famed naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace.

Between 1854 and 1862, Wallace traveled to what is now Indonesia and Malaysia to capture and collect animals for museums. In his book The Malay Archipelago, Wallace recounts hunting orangutans for the museum and describes shooting this adult male eight times and leaving him hanging from a tree until he could return the next day.

As I held the orangutan’s skull in my hands, I considered the others lying in cabinets that stretch from floor to ceiling in the museum’s collection and in natural history museums around the world. Some of these animals died in zoos, but many were captured and killed in the course of natural history collection expeditions in the 19th to early 20th centuries. These ape remains are vital to scientific discovery and are irreplaceable, since current ethical guidelines ensure that remains will never be obtained in this manner again. Nevertheless, this history is worth confronting.

Today museum collections broadly are in the midst of a reckoning regarding their colonial, extractivist legacies. They face scrutiny from the public and researchers on how to best curate, research, and pay respects to cultural objects and, especially, human remains. These conversations typically don’t involve nonhuman primate skeletal remains, even though living great apes have been granted a high degree of legal protection in recent years.

We (the authors of this essay) have spent many years studying ape remains and were moved by the stories of the individuals we examined—stories that need not remain invisible. To bring these animals’ lives to light, we pieced together archival information and animal names in zoo records. We connected data about pieces of individuals housed across different areas of each museum, if not in entirely different institutions.

We came together with two other colleagues who noticed the same issues and co-wrote a piece for Evolutionary Anthropology. We envisioned how a more empathetic and decolonial curatorial initiative could be put into place within great ape skeletal collections research. In this piece, we aim to reimagine how we all—as researchers, curators, and members of the viewing public—might approach these apes, learning from their deaths and paying respects to their lives.

THE CRUEL HISTORY OF APE COLLECTING

Haloko, a western lowland gorilla, was captured from Cameroon circa 1970 when she was around 3 years old. She was taken to the Philadelphia Zoo, then to New York’s Bronx Zoo, then in 1989 to the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., where she spent the rest of her life.

Although she successfully gave birth to four living offspring, she was unable to care for them. This is not uncommon among captive great apes, particularly in the past. Females who were not reared by their mothers or did not witness maternal bonds are at a great disadvantage when faced with caring for their own infant. Haloko’s mothering duties were handed over to other female gorillas and animal care staff.

After Haloko died in 2011 at approximately age 44, her remains were placed in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Her body still retains the scars of her ordeals. Her dental stress line—a line of reduced enamel caused by stress—most likely corresponds to the time of her capture in the wild. It is the deepest stress line ever measured in an ape or extinct hominin.

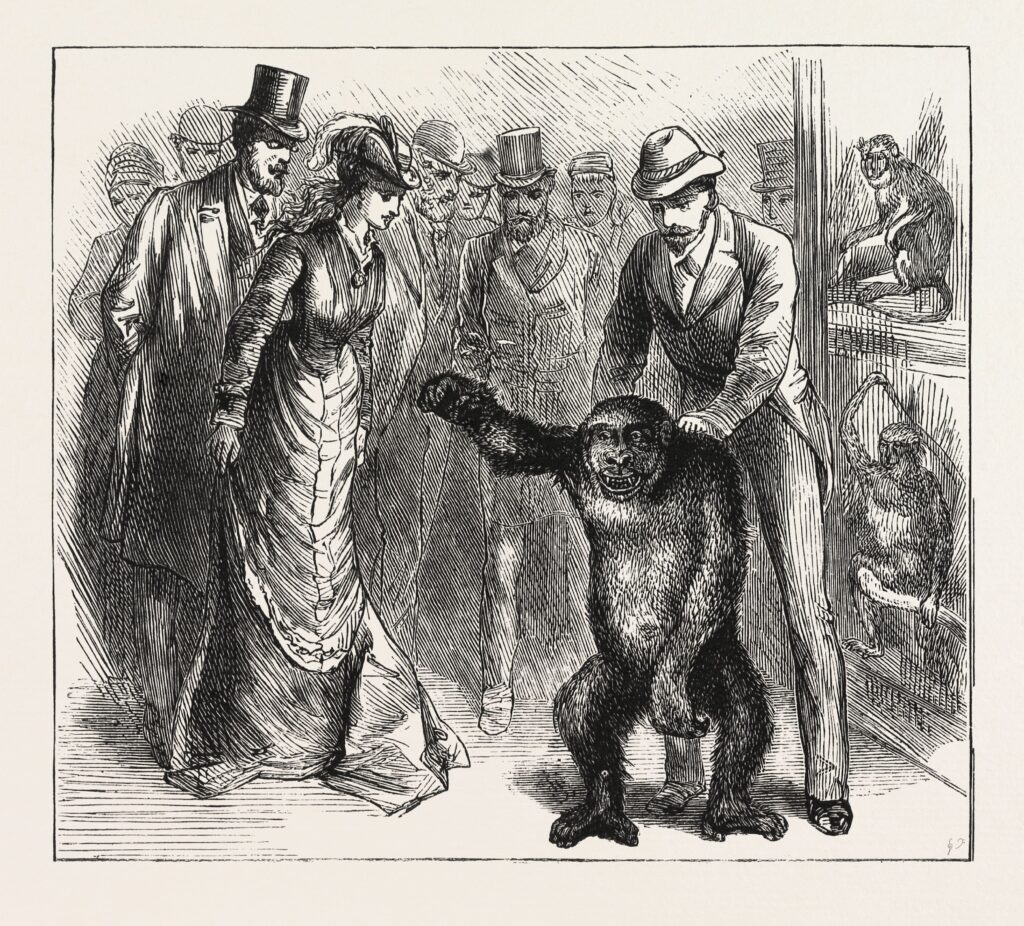

While modern zoos are just as vital for the preservation and conservation of primates as museum collections are for the advancement of scientific research, the now antiquated process of acquiring living apes was galling. In one particularly chilling 1928 account, a collector describes wrestling a young gorilla to the ground and “putting a bag over its head, then beating it into submission.” Capturing infants for zoos often involved killing entire family groups, since adults would come to the protection of the babies.

After such horrific ordeals, it is no surprise that many apes died during the grueling journey to their new “homes.” An 1889 report describes a sad attempt to transfer a family of orangutans from Singapore to the Philadelphia Zoological Garden: “The female and the young one died, however, in transit, and the surviving male reached the Gardens on June 13th in such a weak state that he died on the following day.”

The 19th- and 20th-century practices of killing apes for natural history museums and private collections was considered a noble endeavor at the time. But it, too, was undeniably cruel by today’s standards. Apes were often shot out of trees, their limbs breaking as they fell. In one incident, a mother ape was carrying an infant when she was shot down from a tree and broke both her leg and jaw.

These practices were not only morally reprehensible, they also did a disservice to science. Anyone familiar with trauma knows that the body is left with scars. Some are obvious; others are not. Bone fractures and dental stress lines are still visible in ape remains today. Malnutrition and extreme stress, perhaps from capture or the journey across the sea, can change the body. These alterations could potentially lead researchers to misleading conclusions about ape morphology.

In addition, colonial prejudices and biases still impact the study of great apes in museums. Researchers have found that historic male collectors’ desires to capture impressively large male animals led to the documented male sex bias in museums’ animal collections. Evidence of this can be traced to the words of early collectors. In his book In Brightest Africa (1923), collector Carl Akeley wrote:

“I picked out one [gorilla] that I thought to be an immature male. I shot and killed it and found, much to my regret, that it was a female. As it turned out, however, she was such a splendid large specimen that the feeling of regret was considerably lessened. This female had a baby which was hustled off by the rest of the band. The baby was crying piteously as it went.”

Furthermore, many modern-day researchers have not studied the remains of captive animals because there is an ongoing misconception—which arose from colonialist ideology—that wild animals are representative of a pristine natural state, while captive individuals have been altered. One need only review the specimen sample in academic papers to identify this persistent pattern of captive animal exclusion in biological anthropology.

Haloko’s remains have been understudied because her museum label states “captive.” However, when we take the time to examine her skeleton, we find novel insights into the capacity of gorilla biology to withstand stress and trauma. Below her skull, her bones show signs of her locomotion shifting as a result of her environment. And her teeth stand as an example of one of the most extreme stressors apes are known to endure—being taken from her mother and shipped in a cage to another continent.

The orangutan killed by Wallace turned out to have a unique constellation of adult teeth and a juvenile-looking face that lacked the large cheek pads characteristic of many male orangutans. His unique features were missed for over a century because of a depersonalizing practice that continues to impact science today: His skin was kept separate from his skeleton.

Adopting new practices that honor the dignity of primates in collections could not only usher in ethical conversations but also scientific discoveries.

REIMAGINING MORE ETHICAL APE COLLECTIONS

We are not the first to address these issues. We are standing on the shoulders of others in our field who advocate for a new wave of museum research and collections care. Together, we are proposing ways the scientific community could reckon with the legacies that brought great apes to museums and envision for them a more ethical future.

For example, early primate collectors likely considered each ape to be a specimen representing a species. Today researchers, curators, and the general public could take a more ethical and accurate view: Each ape was an individual with a family, a community, lived experiences, and a unique biology that responded to particular environmental conditions.

To convey this, ape remains could be accompanied by a detailed curatorial sheet that researchers and curators annotate with life history and observations. This would ensure that museum records evolve with new discoveries. Documenting information such as age estimates, pathological observations, and links to scientific studies would also give researchers a clearer picture of each individual, leading to more robust science. While many researchers assume details about apes’ life history are unavailable, we have found that this information can often be uncovered through research, archival work, and collaboration.

The curatorial record would also include the apes’ names (in cases when zoo animals such as Holoko were given names) alongside specimen numbers. This would create a more personal connection to each ape. It would also help in tracking apes’ histories across institutions, since each museum assigns skeletons a different specimen number, but names usually remain consistent.

In written materials and conversations, people could refer to nonhuman primates as “he,” “she,” “who,” and “whom” rather than “that” and “it.” This would acknowledge the primates’ identities as individuals with life stories. For example, one could talk about “the orangutan who was shot” instead of “the orangutan that was shot.”

We also propose piecing individual apes back together in museums. In many instances, ape skulls and skins are stored separately from the rest of their skeletons. This practice is a relic of an earlier belief that anatomical regions were divided by artificial boundaries rather than functioning as integrated systems. Today it unintentionally reinforces the idea that ape remains are a mere collection of body parts. Putting remains back together would encourage people to see them as individuals who lived lives. It would also help researchers collect more accurate and contextualized data.

Furthermore, we advocate redressing the extractivist collection of apes, which occurred when scientific colonialism perceived countries in the Global South as suppliers of specimens for the Global North. This decolonization may involve digital repatriation, physical repatriation, co‐ownership of remains, and/or giving priority access to researchers from postcolonial countries. There must be collaborative discussions regarding the future of great ape skeletal remains that center and amplify the voices of people from countries of origin.

We believe these interventions will create a more empathic science of ape remains that allows us all to think deeply about the dignity and respect owed to these individuals who, in death, still spark scientific discoveries.

In our experience, this work has revealed the incredible resilience of apes. As we studied and continue to study ape skeletons—etched with evidence of the suffering they endured and their adaptations to ever-evolving anthropogenic spaces—we can’t help but imagine with empathy the relentless drive for survival that carried them through unimaginable pain. It is a reminder of their strength—and a call to action.

Together, we can rewrite their story, transforming a history of extraction and exploitation into one of respect and dignity.