People Are Not Peas—Why Genetics Education Needs an Overhaul

On a lengthy bus ride in the early 1970s, University of Chicago geneticist Richard Lewontin passed the time by doing some novel math.

Lewontin usually kept to the laboratory, studying proteins derived from ground-up fruit flies. Because DNA encodes proteins, this research addressed a fundamental question: How much do individuals of the same species vary genetically?

On the bus, Lewontin turned his attention to humans. Using available data, he computed how protein differences mapped across people around the globe. Contrary to what scientists assumed at the time, he found that most differences existed in every population—meaning the underlying genetic variation was shared across humanity, not sorted by geographic region or prevailing “racial” categories.

Lewontin published his calculations in a short paper in 1972 that ended with this definitive conclusion: “Since … racial classification is now seen to be of virtually no genetic or taxonomic significance either, no justification can be offered for its continuance.” His results have been replicated time and again over the last 50 years, as datasets have ballooned from a handful of proteins to hundreds of thousands of human genomes.

But despite huge strides in genetics research—leaving no doubt about the validity of Lewontin’s conclusions—genetics curricula taught in U.S. secondary and post-secondary schools still largely reflect a pre-1970s view.

This lag in curricula is more than a worry for those in the ivory tower. Increasingly, genomics plays a leading role in health care, criminal justice, and our sense of identity and connection to others. At the same time, scientific racism is on the rise, reaching more people than ever thanks to social media. Outdated education fails to dispel this disinformation.

From the basic genetics taught in K–12 schools to university courses, biology curricula desperately need an overhaul.

HOW DNA DIFFERS

I am a biological anthropologist who uses genomic data to answer questions about primate and human evolution. When I began my doctoral studies a decade ago, we learned about Lewontin’s paper for its historical significance, but his findings were old news.

Prior to his calculations, many scientists expected to find substantial genetic differences between people from different geographic regions or races. Say, Indigenous people in Africa would carry marker A, but all Indigenous people in the Americas would have marker C.

Lewontin found a quite different result: The vast majority (greater than 85 percent) of genetic differences existed among individuals from the same geographic region. This equates to some Indigenous people in Africa and some Indigenous people in the Americas carrying the DNA letter (molecular base) A, while other Africans and Indigenous people in the Americas carry the C. Most human genetic variation is shared across all the continents—or the racial groups invented during and since European colonial expansion.

Equivalent calculations done over the past two decades—based on genome-wide data from thousands of individuals—have reached the same conclusion: High genetic variation exists within geographic regions, and little variation distinguishes geographic regions.

Most common genetic variants, meaning carried by more than 5 percent of humans, appear across all continents. Only a small portion of these variants are exclusively found on one continent, and those continent-specific variants tend to be rare among members of a population, where they are found.

GENOMIC INSIGHTS

In addition to genomes from living humans, DNA extracted from ancient humans over the past two decades has revealed incredible insights. Across time, past humans frequently migrated, mated with, or displaced people they encountered in other regions—resulting in a tangled tree of human ancestry. The ancient DNA results refute any notion of deep, separate roots for humans in different geographic regions.

Also, contemporary researchers better understand how DNA variation contributes to differences in human traits. Scientists now know that most of our biological attributes are influenced by many genetic variants and their effects vary in response to assorted environmental factors. For example, thousands of genetic variants influence height, and their effect is modified by childhood nutrition and infections.

As for race, researchers have shown conclusively that historical racial categories are not based in any inherent aspect of our biology. But that doesn’t mean these racial categories and biology don’t affect people’s lived experiences.

As laid out by a major professional association for biological anthropologists, race is a social reality that affects our biology. For the last several hundred years in the U.S. and other colonized lands, racism has influenced people’s access to nutritious food, education, economic opportunities, health care, safety, and more. As a consequence, and precisely because of the environmental influence on most traits, the social construction of race is a risk factor for many health conditions and outcomes, including maternal and infant mortality, asthma, and COVID-19 severity.

Physicians and researchers are increasingly recognizing that racial health disparities are a result of racism not innate racial differences.

LAGGING LESSONS

When I started teaching at Duke University five years ago, I assumed most college students would have received a basic genetics education—one that reflected fundamental updates in genetics research over the past 50 years.

Not so. I quickly learned most undergraduates in my classes still hold the pre-Lewontin belief that human genetic variation predominately sorts geographically. Many students also thought race was based in genetic differences and that single mutations could explain complex traits in humans, such as risk for most diseases.

I doubt the students in my classes were unique. Studies have shown inconsistent and ahistorical presentations of genetics likely contribute to students’ confusion about the nature of genes and their role in our lives.

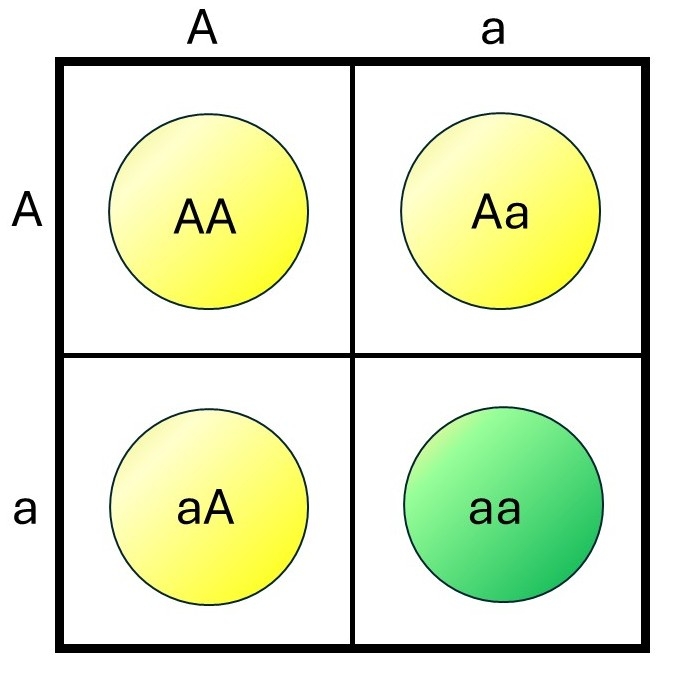

Standard U.S. high school textbooks give little attention to human biological variation. Instead, most books focus on topics like Gregor Mendel, the 19th-century Austrian priest who derived “laws” of inheritance from tracing observable traits when crossing pea plant varieties. (Remember those Punnett squares with green and yellow peas, or wrinkly and round ones?)

I, along with others, am concerned that this focus instills and reinforces a false pre-Lewontin view that humans, like Mendel’s peas, come in discrete types. In reality, early studies of peas and other inbred, domesticated species have little relevance for human genetics.

And when U.S. high school, college, and medical school classes do cover human diversity, the lessons mostly focus on disease prevalence—and abound with racialized terminology. For example, students often learn that sickle cell anemia primarily affects African Americans. But sickle cell anemia is neither unique to nor characteristic of people with African ancestry. Rather, the genetic variant that causes sickle cells occurs more frequently in people with recent ancestry in parts of Africa, Europe, and South Asia—regions where malaria is or recently was endemic.

This distinction may seem like splitting hairs. But it turns out such distinctions are consequential.

Scholars such as biologist and educator Brian Donovan have tested how these simplified examples influence students’ thinking. In multiple studies, he compared classrooms using standard textbooks with those incorporating more updated and accurate content on human biological variation. Students who received the typical—outdated—genetics education were more likely to think race is inherently biological and that genetic differences among races explain differences in life outcomes. The dated material also decreased students’ support for efforts meant to redress racial inequity.

On the flipside, that research also showed these measures are reversed by content that includes the global distribution of most genetic variation and the complex, multifactored basis of most human traits.

Educators can either perpetuate or dispel misconceptions, depending on how they teach genetics.

SLAYING A ZOMBIE IDEA

I consider the notion that historical racial categories are based in biology to be a “zombie idea,” an idea that perpetually reanimates despite repeated empirical falsification. Zombie ideas of biological race probably persist when deeply held views, particularly those important to our social identities, undermine rational appraisal of evidence. As a result, some have argued that it is futile to combat racism with scientific evidence.

Helping the zombie persist, direct-to-consumer genetic tests, like those offered by 23andMe and AncestryDNA, can reinforce misconceptions about human variation. These services have become many people’s primary reference point for human genetics information. To be marketable, the companies must communicate their results in simple, familiar ways that also appear meaningful and reliable. This usually entails simplifying genetic ancestry to bright, high-contrast colors, pinned definitively to geographic regions.

Even so, the research by Donovan and others suggests it’s possible to weaken this zombie: Reaching the young via biology curricula can alter their views on race and human variation.

However, few secondary and undergraduate textbooks offer updated content. Pea plant genetics still fill the pages. Adopting new curricula, which complicates material already challenging to teach, is daunting. Implementing more accurate high school genetics curricula will require support from school administrators, parents, and entities like the College Board, which administers the Advanced Placement biology exam.

In the meantime, widespread integration of modern genetics into college and university courses is essential. Higher education does not have the same reach as middle and high school. But college instructors have more agility in adjusting their course content. Plus, instilling up-to-date understanding in future secondary teachers and physicians can have ripple effects.

These changes aren’t easy, but they are possible and worthwhile. In addition to thwarting the spread of racist worldviews, the next generation will be better informed about tricky health care and reproductive decisions. Revised curricula that do not implicitly promote a biological basis for historical racial categories is also less likely to alienate students from underrepresented groups. This change could in turn increase diversity in the scientific workforce, leading to better, healthier science and greater trust between researchers and the public.

Lewontin died at age 92 in 2021. His work was instrumental in demonstrating that race is not based on genetic differences. Many others, like geneticists and gifted communicators Joseph Graves Jr., Charmaine Royal, and Graham Coop, have tirelessly continued to carry this torch.

Educators and families can help by demanding their schools replace curricula focused on 19th-century peas with 21st-century human genetics.