Genetic Factors May Help Explain Athletic Sudden Death

Occasionally, some of the fittest people in the world—from Olympic athletes to football players—die suddenly after a bout of strenuous exercise. Why only some people fall victim isn’t clear, but a new genetic study offers a hint.

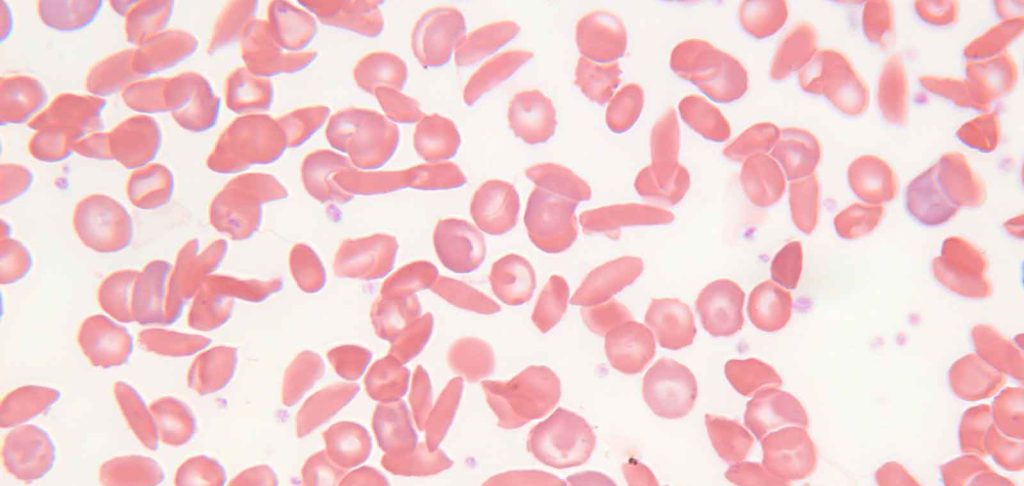

One of the risk factors for athletic sudden death is having a single copy of the abnormal gene variant for sickle cell, a condition called “sickle cell trait” (SCT). People with two copies of this abnormal gene variant have sickle cell anemia, a disease that can turn red blood cells into rigid, sticky, sickle-shaped cells that can restrict how much oxygen gets to the body, block blood flow, cause pain, and lead to blindness or death.

SCT, meanwhile, is generally considered benign most of the time. The conventional wisdom is that people with SCT do not normally have symptoms—except under extreme conditions, like at high altitude, or during intense exercise. In one study that included 13 U.S. college football players who died suddenly of exertion, the risk of death for SCT players was 37 times higher than for players without the trait.

But the reality is a little more complicated, says Lorena Madrigal, a biological anthropologist at the University of South Florida. Some SCT athletes rise to the level of professional football players and experience no problems. Other SCT individuals report having pain after moderate activity. “There’s such tremendous diversity,” says Madrigal.

Now Madrigal and colleagues propose one possible reason for this variation. In the May issue of the Southern Medical Journal, Madrigal and a team of biological anthropologists, a geneticist, and medical doctors show that a small set of gene variants might control the severity of SCT’s effects. Monitoring for those genes, they argue, could reveal who is at highest risk and promote understanding of this often overlooked medical problem.

There are a handful of genes known to change the medical outcomes for people with sickle cell anemia, in particular those genes that modify the amount of a protein called fetal hemoglobin in the blood. The more fetal hemoglobin patients have (as opposed to adult hemoglobin), the more oxygen their bodies have access to and the better they do in the face of anemia caused by blood sickling. “We have known that for decades,” says Madrigal. Perhaps these same genes, she thought, might also impact outcomes for people with SCT.

Madrigal’s team worked with about 30 U.S. football players with SCT. The researchers asked them whether, in comparison with their non-SCT teammates, they experienced extreme thirst, full-body muscle cramps, or pain more often or more intensely. They also took cheek swabs and tested for seven mutations in each player’s genome that are known to be associated with fetal hemoglobin levels. The results, says Madrigal, were “dramatic.” Those participants with genetic dispositions for less fetal hemoglobin had more symptoms, including a diagnosis of blood sickling, whereas those with genetic dispositions for more fetal hemoglobin had built up more muscle mass.

Madrigal admits that the study is small, and she says there is much they’d like to study further, including checking any stored tissue from deceased players for these gene variants and directly testing fetal hemoglobin levels from blood samples. “This is preliminary data,” she says, obtained with a small grant.

It was “very, very difficult” to get participants, Madrigal adds, as SCT is stigmatized in the football community. Athletes are reluctant to be seen or treated differently because of their trait, Madrigal says. “We know there are a lot of athletes that are getting sidelined or not allowed to play because they have SCT,” says Beverley Francis-Gibson, president of the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America in Baltimore.

“I think it is believable and worthy of further study,” says James Taylor of the new results; Taylor is the director of the Center for Sickle Cell Disease at Howard University Hospital in Washington, D.C. The proposed mechanism is plausible, he notes. “Fetal hemoglobin might provide an extra buffer.” But further work is needed to prove the connection: “For population genetics, this [sample size] is ridiculously small,” he says.

SCT is often misunderstood, even in the medical community, says Taylor. For one, many doctors see SCT as essentially asymptomatic—a belief that the new work could help change. “I think this is something that has been glossed over,” Taylor says. “I don’t think we should make SCT a disease, but it is a risk factor.”

Francis-Gibson notes that there is a lot more research needed on sickle cell trait. “It’s rare, but more and more researchers are finding that there are complications that may not be typically connected to sickle cell trait,” she says.

People also tend to misunderstand the condition’s links to ethnicity, adds Francis-Gibson. “Unfortunately, it is categorized as a black condition,” she says. “Yes, it disproportionately affects African Americans, but we know for a fact that it affects many other people.”

In the United States, 8 percent of African Americans have SCT, but the trait also affects people of Arab, Greek, Italian, and Hispanic descent, among others. And one parent with SCT can pass that trait along to their child, no matter the child’s other heritage. Madrigal says she has heard many stories from distressed mothers about their SCT children being dismissed by doctors because, with their blue eyes or red hair, they were “too white” to have SCT—a judgment made even when, for example, a child was taken to the emergency room for extreme pain after soccer practice.

Fortunately, most people—including those with SCT and those without—can benefit from the same basic strategies to stay well, notes Taylor: keep hydrated, build up exercise gradually, and rest when it is hot.

This article was republished at The Atlantic.