Dismantling the “Man the Hunter” Myth

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished with Creative Commons.

IN ANCIENT TIMES, men hunted and women gathered. At least, this is the standard narrative written by and about men to the exclusion of women.

The idea of “Man the Hunter” runs deep within anthropology, convincing people that hunting made us human, only men did the hunting, and therefore evolutionary forces must only have acted upon men. Such depictions are found not only in media, but in museums and introductory anthropology textbooks too.

A common argument is that a sexual division of labor and unequal division of power exists today; therefore, it must have existed in our evolutionary past as well. But this is a just-so story without sufficient evidentiary support, despite its pervasiveness in disciplines like evolutionary psychology.

There is a growing body of physiological, anatomical, ethnographic, and archaeological evidence to suggest that not only did women hunt in our evolutionary past, but they may well have been better suited for such an endurance-dependent activity.

We are both biological anthropologists. I (co-author Cara) specialize in the physiology of humans who live in extreme conditions, using my research to reconstruct how our ancestors may have adapted to different climates. And I (co-author Sarah) study Neanderthal and early modern human health. I also excavate at their archaeological sites.

It’s not uncommon for scientists like us—who attempt to include the contributions of all individuals, regardless of sex and gender, in reconstructions of our evolutionary past—to be accused of rewriting the past to fulfill a politically correct, woke agenda. The actual evidence speaks for itself, though: Gendered labor roles did not exist in the Paleolithic era, which lasted from 3.3 million years ago until 12,000 years ago. The story is written in human bodies, now and in the past.

We recognize that biological sex can be defined using multiple characteristics, including chromosomes, genitalia, and hormones, each of which exists on a spectrum. Social gender, too, is not a binary category. We use the terms female and male when discussing the physiological and anatomical evidence, as this is what the research literature tends to use.

FEMALE BODIES: ADAPTED FOR ENDURANCE

One of the key arguments put forth by “Man the Hunter” proponents is that females would not have been physically capable of taking part in the long, arduous hunts of our evolutionary past. But a number of female-associated features, which provide an endurance advantage, tell a different story.

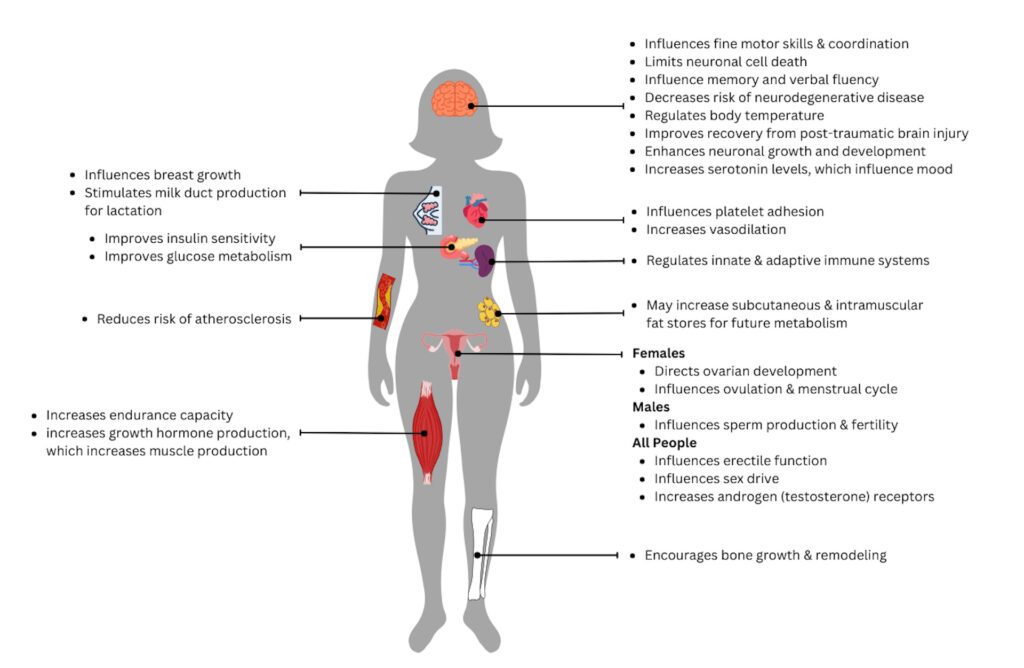

All human bodies, regardless of sex, have and need both the hormones estrogen and testosterone. On average, females have more estrogen and males more testosterone, though there is a great deal of variation and overlap.

Testosterone often gets all the credit when it comes to athletic success. But estrogen—technically the estrogen receptor—is deeply ancient, originating somewhere between 1.2 billion and 600 million years ago. It predates the existence of sexual reproduction involving egg and sperm. The testosterone receptor originated as a duplicate of the estrogen receptor and is only about half as old. As such, estrogen, in its many forms and pervasive functions, seems necessary for life among both females and males.

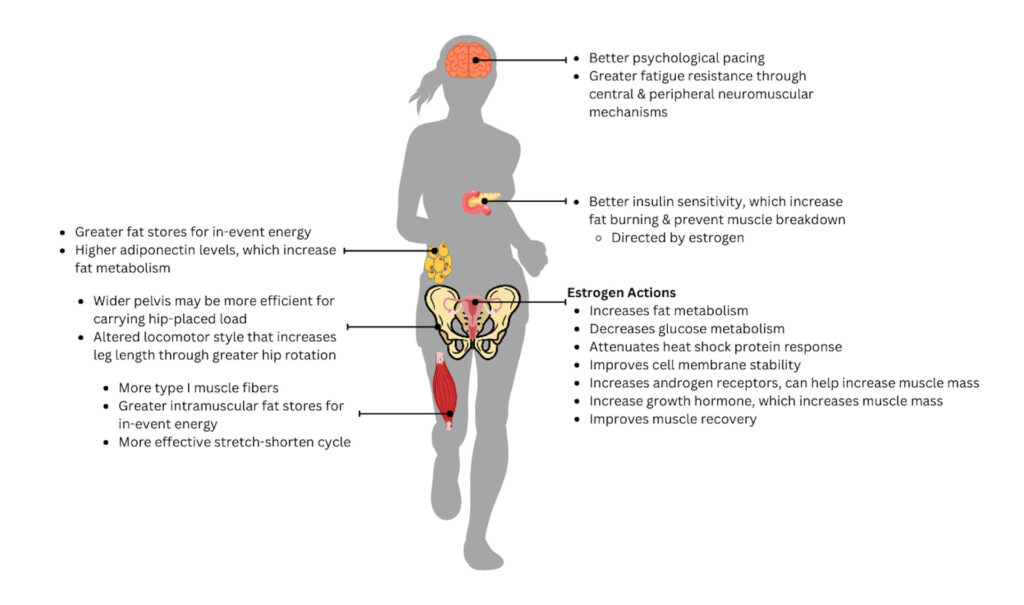

Estrogen influences athletic performance, particularly endurance performance. The greater concentrations of estrogen that females tend to have in their bodies likely confer an endurance advantage—an ability to exercise for a longer period of time without becoming exhausted.

Estrogen signals the body to burn more fat—beneficial during endurance activity for two key reasons. First, fat has more than twice the calories per gram as carbohydrates do. And it takes longer to metabolize fats than carbs. So, fat provides more bang for the buck overall, and the slow burn provides sustained energy over longer periods of time, which can delay fatigue during endurance activities like running.

In addition to their estrogen advantage, females have a greater proportion of type I muscle fibers relative to males.

These are slow oxidative muscle fibers that prefer to metabolize fats. They’re not particularly powerful, but they take awhile to fatigue—unlike the powerful type II fibers that males have more of but that tire rapidly. Doing the same intense exercise, females burn 70 percent more fats than males do, and unsurprisingly, are less likely to fatigue.

Estrogen also appears to be important for post-exercise recovery. Intense exercise or heat exposure can be stressful for the body, eliciting an inflammatory response via the release of heat shock proteins. Estrogen limits this response, which would otherwise inhibit recovery. Estrogen also stabilizes cell membranes that might otherwise be damaged or rupture due to the stress of exercise. Thanks to this hormone, females incur less damage during exercise and are therefore capable of faster recovery.

WOMEN IN THE PAST LIKELY DID EVERYTHING MEN DID

Forget the Flintstones’ nuclear family, with a stay-at-home wife. There’s no evidence of this social structure or gendered labor roles during the 2 million years of evolution for the genus Homo until the last 12,000 years, with the advent of agriculture.

Our Neanderthal cousins, a group of humans who lived across Western and Central Eurasia approximately 250,000 to 40,000 years ago, formed small, highly nomadic bands. Fossil evidence shows females and males experienced the same bony traumas across their bodies—a signature of a hard life hunting deer, aurochs, and woolly mammoths. Tooth wear that results from using the front teeth as a third hand, likely in tasks like tanning hides, is equally evident across females and males.

Our Paleolithic ancestors lived in a world where everyone performed multiple tasks. It was not a utopia, but it was not a patriarchy.

This nongendered picture should not be surprising when you imagine small-group living. Everyone needs to contribute to the tasks necessary for group survival—chiefly, producing food and shelter, and raising children. Individual mothers are not solely responsible for their children; in forager communities, the whole group contributes to child care.

You might imagine this unified labor strategy then changed in early modern humans, but archaeological and anatomical evidence shows it did not. Upper Paleolithic modern humans leaving Africa and entering Europe and Asia show very few sexed differences in trauma and repetitive motion wear. One difference is more evidence of “thrower’s elbow” in males than females, though some females shared these pathologies.

And this was also the time when people were innovating with hunting technologies like atlatls (spear throwers), fishing hooks and nets, and bow and arrows—alleviating some of the wear and tear hunting would take on their bodies. A recent archaeological experiment found that using atlatls decreased sex differences in the speed of spears thrown by contemporary men and women.

Even in death, there are no sexed differences in how Neanderthals or modern humans buried their dead or the goods affiliated with their graves. These indicators of differential gendered social status do not arrive until agriculture, with its stratified economic system and monopolizable resources.

All this evidence suggests Paleolithic women and men did not occupy differing roles or social realms.

Critics might point to recent forager populations and suggest that since they are using subsistence strategies similar to our ancient ancestors, their gendered roles are inherent to the hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

However, there are many flaws in this approach. Foragers are not living fossils, and their social structures and cultural norms have evolved over time and in response to patriarchal agricultural neighbors and colonial administrators. In addition, ethnographers of the last two centuries brought their sexism with them into the field, and it biased how they understood forager societies. For instance, a recent reanalysis showed that 79 percent of cultures described in ethnographic data included descriptions of women hunting; however, previous interpretations frequently left them out.

DISCARD THE CAVEMAN MYTHS

The myth that female reproductive capabilities somehow render them incapable of gathering any food products beyond those that cannot run away does more than just underestimate Paleolithic women. It feeds into narratives that the contemporary social roles of women and men are inherent and define our evolution. Our Paleolithic ancestors lived in a world where everyone in the band pulled their own weight, performing multiple tasks. It was not a utopia, but it was not a patriarchy.

Certainly, accommodations must have been made for group members who were sick, recovering from childbirth, or otherwise temporarily incapacitated. But pregnancy, lactation, childrearing, and menstruation are not permanently disabling events, as researchers found among contemporary Agta people of the Philippines who continue to hunt during these life periods.

Suggesting that the female body is only designed to gather plants ignores female physiology and the archaeological record. To ignore the evidence perpetuates a myth that only serves to bolster existing power structures.