Was Our Skin Meant for the Sun?

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished with Creative Commons.

HUMAN BEINGS HAVE a conflicted relationship with the sun. People love sunshine, but then get hot. Sweat gets in your eyes. Then there are all the protective rituals: the sunscreen, the hats, the sunglasses. If you stay out too long or haven’t taken sufficient precautions, your skin lets you know with an angry sunburn. First the heat, then the pain, then the remorse.

Were people always this obsessed with what the sun would do to their bodies? As a biological anthropologist who has studied primates’ adaptations to the environment, I can tell you the short answer is “no,” and they didn’t need to be. For eons, skin stood up to the sun.

SKIN, BETWEEN YOU AND THE WORLD

Human beings evolved under the sun. Sunlight was a constant in people’s lives, warming and guiding them through the days and seasons. Homo sapiens spent the bulk of our ancient and recent history outside, mostly naked. Skin was the primary interface between our ancestors’ bodies and the world.

Human skin was adapted to whatever conditions it found itself in. People took shelter, when they could find it, in caves and rock shelters, and got pretty good at making portable shelters from wood, animal skins, and other gathered materials. At night, they huddled together and probably covered themselves with fur “blankets.” But during the active daylight hours, people were outdoors, and their mostly bare skin was what they had.

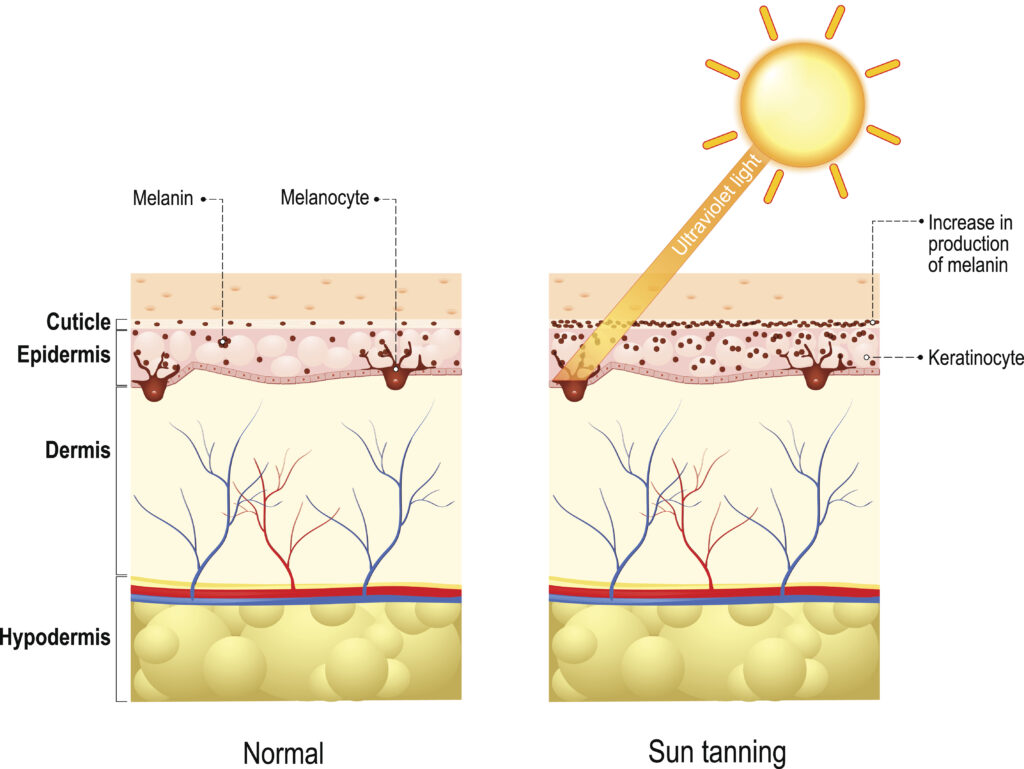

During a person’s lifetime, skin responds to routine exposure to the sun in many ways. The surface layer of the skin—the epidermis—becomes thicker by adding more layers of cells. For most people, the skin becomes gradually darker as specialized cells kick into action to produce a protective pigment called eumelanin.

This remarkable molecule absorbs most visible light, causing it to look very dark brown, almost black. Eumelanin also absorbs damaging ultraviolet radiation. Depending on their genetics, people produce different amounts of eumelanin. Some have a lot and are able to produce a lot more when their skin is exposed to sun; others have less to start out with and produce less when their skin is exposed.

My research on the evolution of human skin pigmentation has shown that the skin color of people in ancient times was tuned to local environmental conditions, primarily to local levels of ultraviolet light. People who lived under strong UV light—like you’d find near the equator—year in and year out had darkly pigmented and highly tannable skin capable of making a lot of eumelanin. People who lived under weaker and more seasonal UV levels—like you’d find in much of Northern Europe and Northern Asia—had lighter skin that had only limited abilities to produce protective pigment.

With only their feet to carry them, our distant ancestors didn’t move around much during their lives. Their skin adapted to subtle, seasonal changes in sunlight and UV conditions by producing more eumelanin and becoming darker in the summer and then losing some pigment in the fall and winter when the sun wasn’t so strong. Even for people with lightly pigmented skin, painful sunburns would have been exceedingly rare because there was never a sudden shock of strong sun exposure. Rather, as the sun strengthened during spring, the top layer of their skin would have gotten gradually thicker over weeks and months of sun exposure.

This is not to say that the skin would have been undamaged by today’s standards: Dermatologists would be appalled by the leathery and wrinkled appearance of the sun-exposed skin of our ancestors. Skin color, like the levels of sun itself, changed with the seasons and skin quickly showed its age. This is still the case for people who live traditional, mostly outdoor, lives in many parts of the world.

There is no preserved skin from thousands of years ago for scientists to study, but we can infer from the effects of sun exposure on contemporary people that the damage was similar. Chronic sun exposure can lead to skin cancer but rarely of the variety—melanoma—that would cause death during reproductive age.

INDOOR LIVING CHANGED SKIN

Until around 10,000 years ago—a drop in the bucket of evolutionary history—human beings made their living by gathering foods, hunting, and fishing. Humanity’s relationship with the sun and sunlight changed a lot after people started to settle down and live in permanent settlements. Farming and food storage were associated with the development of immovable buildings. By around 6000 B.C., many people throughout the world were spending more time in walled settlements and more time indoors.

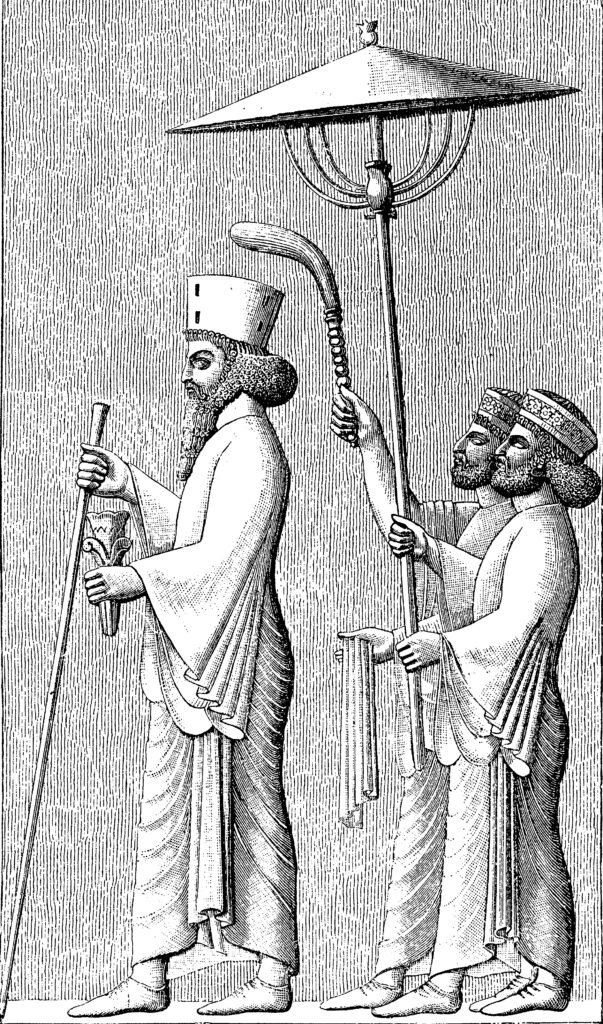

While most people still spent most of their time outside, some stayed indoors if they could. Many of them started protecting themselves from the sun when they did go out. By at least 3000 B.C., a whole industry of sun protection grew up to create gear of all sorts—parasols, umbrellas, hats, tents, and clothing—that would protect people from the discomfort and inevitable darkening of the skin associated with lengthy sun exposure. While some of these were originally reserved for nobility—such as the parasols and umbrellas of ancient Egypt and China—these luxury items began to be made and used more widely.

In some places, people even developed protective pastes made out of minerals and plant residues—early versions of modern sunscreens—to protect their exposed skin. Some, like the thanaka paste used by people in Myanmar, still persists today.

An important consequence of these practices in traditional agricultural societies was that people who spent most of their time indoors considered themselves privileged, and their lighter skin announced their status. A “farmer’s tan” was not glamorous: Sun-darkened skin was a penalty associated with hard outdoor work, not the badge of a leisurely vacation. From Great Britain to China, Japan, and India, suntanned skin became associated with a life of toil.

As people have moved around more and faster over longer distances in recent centuries, and spend more time indoors, their skin hasn’t caught up with their locations and lifestyles. Your levels of eumelanin probably aren’t perfectly adapted to the sun conditions where you live and so aren’t able to protect you the same way they might have your ancient ancestors.

Even if you’re naturally darkly pigmented or capable of tanning, everyone is susceptible to damage caused by episodes of sun exposure, especially after long breaks spent completely out of the sun. The “vacation effect” of sudden strong UV exposure is bad because a sunburn signals damage to the skin that is never completely repaired. It’s like a bad debt that presents itself as prematurely aged or precancerous skin many years later. There is no healthy tan—a tan doesn’t protect you from further sun damage; it’s the sign of damage itself.

People may love the sun, but we’re not our ancestors. Humanity’s relationship with the sun has changed, and this means changing your behavior to save your skin.