Are People Projecting Racist Stereotypes Onto Squirrels?

SQUIRREL CHATTER

A few years back, one of us was chatting with neighbors when the subject of squirrels came up. While most squirrels in the small New Jersey town were gray, everyone had noticed quite a few with black fur as well.

“You know, the black ones are more aggressive than the gray ones,” a neighbor authoritatively announced.

Not long after, the same claim was made by a student at Rutgers University, where we teach. He had heard it from one of his parent’s friends back home in the Bronx.

While some assume gray and black squirrels belong to different species, they don’t. They are all members of the same species, Sciurus carolinensis, commonly known—despite their variable fur colors—as the eastern gray squirrel. The agile rodents most often grow gray coats, but due to minor genetic differences, they can instead develop fur colored cinnamon, reddish, silvery, white, albino, or black.

Given that black and gray squirrels belong to the same species, could the black ones really be more aggressive than the grays?

The internet has thoughts. Numerous Reddit posts repeat the black squirrel stereotype. One Redditor claimed, “All of greater Toronto is pretty much 100% black squirrels now. The mutation also makes them more aggressive, and they outcompete the greys. … The mutation also carries higher levels of testosterone.” Another agreed: “We have them down in western New York, and they are mean little dudes compared to the others!”

Others insist that, despite how all this talk about colors and behaviors may sound, black squirrels’ bad reputations have “nothing to do with racism.”

Some satirical posts imply racism does underlie the claims: “My neighborhood gentrified our squirrels in the ’60s,” wrote one Redditor. The black squirrels “tend to be less educated and often commit crime on other black squirrels,” said a comment we read on the now-defunct online forum Yahoo! Answers.

Do black squirrels really show more hostility? Or are people’s perceptions of squirrel behavior colored by racism—so insidious that some individuals unknowingly project racist beliefs onto a completely different species?

SQUIRREL STEREOTYPES VERSUS SCIENCE

We decided to combine our areas of expertise to dig into this issue. Cronk spends most of his time studying human behavior, especially cooperation, from an evolutionary perspective. Palombit investigates the behavior of nonhuman primates, particularly baboons, using the same perspective.

Native to Eastern North America, eastern gray squirrels now also bound across parts of Western North America, Europe, and other lands where they have been introduced. While many squirrel species dwell in underground burrows, eastern grays build nests in trees out of dry leaves. Highly social, the critters communicate using a variety of vocalizations, tail flicking, and facial expressions. Although they mostly prefer nuts, fruit, and other vegetarian fare, the squirrels have also been observed eating insects, birds’ eggs, and even small birds themselves.

Geneticists have found that the squirrels’ black coloration is caused by a particular variant of the MC1R gene, involved in skin and hair color across mammals. Social and mass media have spread claims about the behavior of this black variety on both sides of the Atlantic.

In 2008, the U.K.-based Daily Mail reported: “The black squirrel has arrived—and is rampaging through parks and woodlands. Scientists say the testosterone-charged black is fitter, faster, and more fiercely competitive than both reds and greys.” (“Reds” refers to the Eurasian red squirrel, which is native to the U.K.) Accompanying the article, a photo of a black squirrel was captioned: “Cute but deadly: They may look harmless, but ‘mutant’ squirrels have left the grey squirrel population in fear.”

Another Daily Mail article a year later rehashed the characterization: “The testosterone-fuelled black squirrels are faster, fitter, fiercely territorial, and more aggressive, beating greys to food and mates.”

References to “testosterone-fuelled” and “fiercely territorial” animals suggest there might be scholarship backing these claims. We expected to find studies that compare how different colored squirrels engage in “aggressive” behavior—initiating fights with other squirrels, chasing conspecifics from their territories and food sources. And certainly, researchers would have measured differences in squirrel testosterone levels.

But we searched scientific articles and found no such evidence.

On the contrary, environmental scientists Eric J. Gustafson and Larry W. VanDruff watched squirrels in Syracuse, New York, across one year in the early 1980s. Based on the number of times squirrels of different colors chased other squirrels away from feeders, they concluded that “neither color morph was more dominant in aggressive encounters at feeding stations.”

And the idea that black squirrels have more testosterone? Despite how superficially scientific that may sound, our search surfaced no scientific data supporting the assertion. It seems no one has even studied the question.

Despite the decades passed since Gustafson and VanDruff’s observations, popular belief in more aggressive black squirrels persists. So, we decided to reinvestigate the matter.

SQUIRREL CENSUS IN CENTRAL PARK

It might have taken us (or student assistants) hundreds of hours to observe enough squirrel antics to answer our research question: Do black squirrels behave more aggressively than gray ones? But fortunately, a ready-to-go dataset already existed.

In 2018, a researcher recruited more than 300 volunteer “Squirrel Sighters” to conduct the Central Park Squirrel Census. This citizen science project divided New York City’s Central Park into 350 squares, each about the size of two American football fields, including endzones. Sighters spent 20 minutes in each square, first walking its perimeter and then its interior, once in the morning and once in late afternoon. The participants noted each squirrel’s coloration and activity, such as eating, running, climbing a tree, or—most relevant to our question—chasing another squirrel aggressively.

Although collected by nonprofessionals, the Squirrel Census had one big advantage over data that we could have gathered ourselves: We knew the hypothesis we were testing, but none of the Squirrel Sighters were aware of our work. If anything, the folk belief about fur color–based behavior might have biased sighters, making them more likely to report aggressive acts by black squirrels.

The results were clear: Black squirrels did not initiate chases more often than gray or cinnamon ones, who also reside in Central Park.

The only fur color–based behavioral difference was that black squirrels were more likely to scurry away from people. If anything, Central Park’s black squirrels appeared more timid than the other varieties.

An earlier study found that urban squirrels living in areas more densely populated by other squirrels tended to chase and bite their conspecifics more. Perhaps, then, black squirrels in Central Park may simply inhabit portions of the park with fewer squirrel mates, leading to fewer aggressive acts. To test for that possibility, we looked at the numbers of squirrel sightings in the squares with and without black squirrels observed.

Turns out, the black ones were spotted more often in high- rather than low-density parts of the park. Meaning, black squirrels tended to live in high-density patches, where aggressiveness might be expected, and yet were not more aggressive.

MULTISPECIES DISCRIMINATION

Our study refutes the notion that black squirrels are more aggressive than gray ones—at least for the resident rodents of Central Park in 2018. Where, then, does this erroneous belief come from, and why does it persist?

It may not be a coincidence that so-called scientific racists have claimed, without evidence, that people who identify as Black men have higher testosterone levels, which makes them more aggressive relative to people of other “races.” Meanwhile, no actual scientific data have shown differences in testosterone levels or aggressiveness between Black men and others. In fact, the biological basis of “racial groups” has been refuted.

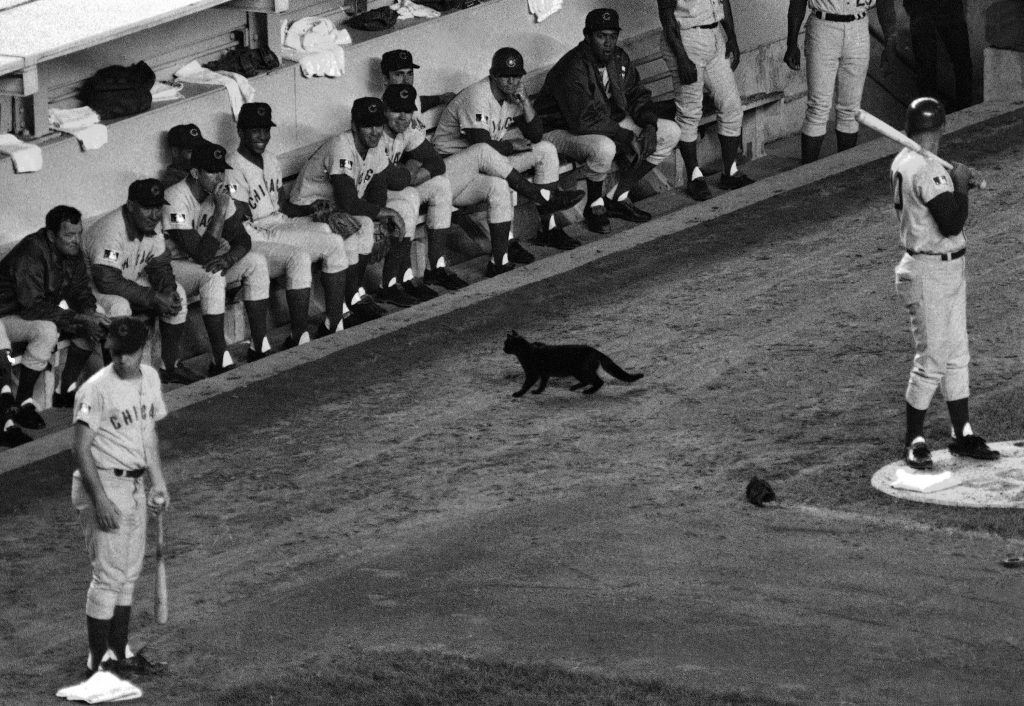

And black squirrels might not be the only animals stigmatized and misunderstood due to their color. Superstitions about the dangers posed by black cats, for example, have brewed in some cultures for centuries. More recently, a study conducted at an animal shelter in Columbus, Ohio, found that dogs with names that are perceived as White, such as Ben and Maggie, were adopted more quickly than those with names perceived as Black, such as Rihanna and Tyson.

We’re left to conclude that beliefs about black squirrels may be a projection of racist ideas and attitudes onto—of all things—a species of wild rodent that lives alongside people. The false scientific veneer created by references to testosterone undoubtedly makes the idea sound more plausible, even to people who are not consciously trying to be racist.

We do not know whether these squirrel stereotypes feed back into or reinforce racist views about people. But the beliefs could certainly harm black-furred squirrels if people view the animals as dangerous pests rather than wildlife worth protecting.

AN ALTERNATIVE OUTLOOK

Animosity toward black squirrels does not exist everywhere. For decades, Princeton, New Jersey, has been blessed with a large population of black squirrels, who have become a beloved symbol of the town. Images of the rodents adorn Princeton-themed coffee mugs, T-shirts, and bumper stickers.

Similarly, Marysville, Kansas, adopted the black squirrel as its mascot in 1972. “Black Squirrel Song” is the city’s anthem and regional artists created dozens of 5-foot-tall black squirrel sculptures on display. Black squirrels also serve as the mascot of athletic teams at Pennsylvania’s Haverford College. In Ohio, Kent State University Press named one of its publishing lines Black Squirrel Books, inspired by the “frisky, industrious black squirrels” seen around campus.

Perhaps such enthusiasm can spread the message: Black squirrels are not bullies. Put the rumors to rest and embrace our black squirrel friends! (Just not literally because they, like all squirrels, are wild animals.)