Athletics, IQ, Health: Three Myths of Race

Our recent book, Racism, Not Race, tackles a big lie: The idea that human beings have biological races.

Biological races do not exist in humans. Why, then, do so many people in the United States and other parts of the world continue to believe in this myth?

For one thing, humans vary. That’s obvious to our eyes. We see variation in outward appearances, from hair colors to shoe sizes to skin color. Human variation around the world is wondrous and real.

But genetic research over the past 50 years has shown that human variation does not equal racial difference. In the 1970s, evolutionary biologist Richard Lewontin found that the amount of genetic variation within any human “race” is greater than the variation among races. Interestingly, because our species spent so much of its time in Africa, that’s where the most genetic variation is to be found today. Researchers have shown the variation between two Africans is on average greater than the variation between an African and a European or Asian person.

There are no subgroups within Homo sapiens that have been reproductively isolated long enough to develop anything close to separate races. The concept of race fails to describe human variations or explain how variations evolved.

On the other hand, socially defined races do exist: Humans invented them! The variations between members of our species only take on deeper cultural and political significance when humans in power start dividing and ranking individuals based upon them.

INVENTING THE MYTH OF RACE

The notion and practice of classifying humans into races based on skin color and other physical traits started a few centuries ago. This idea likely evolved from medieval European religious and folk ideas about the importance of blood and inheritance.

The 17th century marked a major turning point in the development of racial hierarchies: That’s when the first enslaved Africans landed in the Virginia colonies. Over time, the notion that groups could be divided and ranked based on natural and God-given traits evolved into a justification for slavery, colonization, and the displacement and genocide of Native Americans. European settlers largely ignored the sovereignty of Native American tribes, including their land rights. Settlers also began to pass race-based laws that upheld ideas of white supremacy, such as giving indentured Europeans legal rights that were not extended to enslaved Africans. By 1691, sex and marriage between Europeans and Africans was legally prohibited as a way to prevent racial mixing.

For a deeper dive into the history of the “race” concept, read on from the archives: “Race Is Real, But It’s Not Genetic.”

Some European and North American natural scientists began to promote pseudoscientific efforts to prove races were real, distinct, and hierarchically arranged. By the 19th century, scientific racism had won the day. For centuries, most scientists upheld the wrong-headed assumption that a biological basis for a hierarchy of races was out there waiting to be found.

Today, even though geneticists have now disproven this myth, biological race remains widely accepted as fact. Beverly Daniel Tatum, a president emerita of Spelman College, describes racial thinking as a type of ideological “smog”: We all breathe racial smog without noticing it. The falsehood of biological race persists because those in power need a way to explain very real inequalities in wealth, health, and other important indicators as if they are natural outcomes of human differences, rather than the result of racist policies, laws, and institutions.

So, let’s put the big myth of biological race on the scrap heap of dead scientific ideas. Once we do that, a cascade of smaller myths that impede racial justice and equity follow. Here are three examples that we, as an evolutionary biologist and biological anthropologist, frequently hear and want to dispel.

Myth 1: Africans and those of African descent are genetically predisposed to run faster and jump higher than Europeans and Asians.

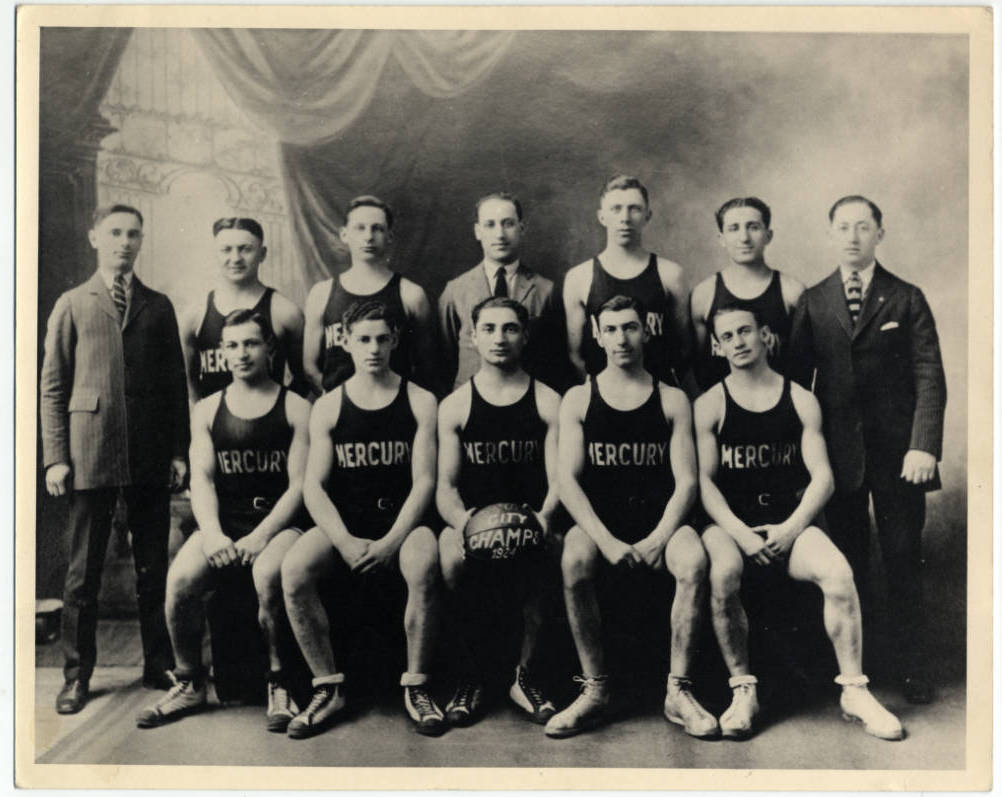

We hear this myth all the time, even among our friends. Perhaps it is because when our friends think of racial differences in athleticism, they envision elite, male athletes in popular sports. Take basketball, for example, where African American athletes make up around 75 percent of professional NBA players. Many people seem to assume that Black players’ dominance in the sport must have a biological or genetic basis—a stereotype widely enforced in popular books and other media.

However, African American players haven’t always dominated basketball. In the 1930s, Jewish American and Irish American teams led the sport. When the Basketball Association of America (later the NBA) started in 1946, the league excluded Black players.

After World War II, basketball began to emerge as a sport of choice in urban African American communities. But it wasn’t because these players were naturally better athletes; it was largely because basketball didn’t require expensive equipment or a lot of space.

Over time, as scholars of sport have shown, the myth of the “natural Black athlete” took hold of the U.S. imagination. African American youth facing limited economic and social opportunities gravitated toward professional sports such as basketball (and football) as a path to success. As sports journalist Reagan Griffin Jr. put it, “The fact of the matter is, Black athletes have collectively achieved what they have because society presented them with few other options.”

Today the composition of professional basketball is again changing following the increase in popularity of the sport in Eastern Europe and around the globe.

Meanwhile, looking at other sports confirms that race has nothing to do with athleticism. Basketball uses similar muscles as swimming and skiing, but in these sports, White Europeans and Australians tend to dominate. At the 2022 Winter Olympics, for instance, White athletes from Norway, which only has a population of around 5 million people, continued their now century-long dominance in skating and skiing.

Athleticism is a complex trait—combining strength, coordination, speed, and other skills. An individual’s athletic prowess is influenced by 120 different genetic markers found across the globe and by a wide range of environmental and cultural factors. Thus, the best explanation for the historical patterns of differences in elite competition relate to economic, social, and cultural factors, not genetic ones.

Myth 2: People of Asian descent achieve the highest levels of education in the U.S. because of higher IQs.

Over the centuries, the idea keeps popping up that some populations—or races—are inherently more intelligent than others. For example, the ancient Romans attributed greater intelligence to those living in subtropical regions and opined on the sluggish intelligence of the Britons, Germans, and French. Defending Europeans, in the 1600s, Sir Francis Bacon argued the opposite. Today in the U.S., stereotypes abound about the cognitive abilities of certain racialized groups, such as the groundless and harmful myth that “Asians are good at math.”

While it’s true that Homo sapiens as a species evolved to have advanced cognitive abilities, scientists have repeatedly failed to provide satisfactory evidence of natural selection for greater intelligence among certain groups. Modern genome-wide association studies—a standard method in genomics research—demonstrate that only a small fraction of the variation in cognitive performance across human populations can be explained by genes. Scientists have also not found any genetic variants associated with cognitive performance that vary dramatically across populations around the world.

Thus, we can understand racialized differences in educational attainment not by genetics, but rather by structured inequalities. Asian Americans, taken as a racialized group, do tend to test higher on standardized tests and are more likely to complete high school and attend elite colleges in comparison to White students. However, there is no scientific evidence to show this group is naturally more intelligent; rather, studies show these students’ success may be due to a complex mix of factors, including attending better schools, U.S. immigration policies that favor highly educated immigrants, and students exerting more academic effort.

The only theories of cognitive performance differences that hold weight are those associated with early child development. And poorer communities and many communities of color have been systematically denied access to quality education. When individuals and groups are deprived of appropriate nutrition, exposed to toxic materials, and/or placed under psychosocial stress, they do not perform as well at cognitive tests as those who do not face those conditions.

It is difficult to quantify the costs—to those communities and society as a whole—of unequal access to education. Some costs, however, are clear. Poor quality education is part of a cycle that includes lack of quality employment, greater chances of incarceration, and greater risk of disease and death.

Myth 3: African Americans are predisposed to certain complex diseases primarily because of genetics.

African Americans fare worse than European Americans on nearly every measure of health. They are more at risk for serious diseases such as diabetes, congestive heart failure, cancers of most every type, and now COVID-19 infections. African American babies are over twice as likely to die in their first year and their mothers are 2.5 times more likely to die during childbirth.

Some researchers have attempted to find genetic differences among races that might explain these persistent disparities in health. But that line of reasoning begins with a false assumption: The idea that races are genetically coherent groups, and therefore one race will have a predominance of the gene that increases risk of disease and others will not. Note that this faulty reasoning is also behind the myths of athletic and intellectual differences. All three of these myths are entirely unsupported by the data.

In this gene-centric era, it is not surprising that biomedical researchers might seek out simple, genetic explanations for variations in risk of disease and death. Genetic differences among individuals can play a role, but risks of complex diseases are, well, complex.

Until recently, researchers have largely ignored the far more significant social, environmental, and economic causes of racial disparities in health outcomes. However, this tendency is starting to change as public health experts—including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—increasingly recognize racism as a public health threat.

A Black woman, for instance, may carry in her body a lifelong history of stress caused by everyday exposure to racism—what public health expert Arline Geronimus has termed “weathering”—that makes her more susceptible to conditions such as hypertension. A Black child from a poor family is more likely to grow up in a food desert and close to a source of pollution—environmental conditions associated with increased rates of diabetes, cancers, and other diseases.

UNDOING THE MYTHS OF RACE

In short, health differences among racialized groups aren’t primarily due to genetics. Inequalities in wealth, education, and housing due to histories of institutional discrimination and racism are much better predictors of health outcomes.

We wrote Racism, Not Race to explain and dispel these and many other myths about race, racism, and human variation. We also focus on one big truth that should be apparent to readers by now: Systemic racism has deadly consequences. In pretty much every sphere of life, racism has all too real biological, social, and economic effects.

The bottom line: We believe we can’t end racism without ending the myth of race. “Race is a human invention,” historian of science Evelynn Hammonds reminds us. “We made it; we can unmake it.”