How Apes Reveal Human History

When I was a kid, every trip to the zoo featured a visit to the orangutan habitat. I was fascinated by the animals’ long fingers, how they took shelter when it started to rain, the affection they showed for their children, and the way they stretched after sitting too long in one position. Sometimes watching them felt like watching any other animal at the zoo, but sometimes it felt like watching people who happen to be visiting a nearby park. I swear I knew what they were thinking and feeling.

As an adult anthropologist, the sense of kinship I felt as a child has been brought into focus. Apes are our closest surviving relatives.

There was a time not so long ago when planet Earth was filled with a variety of our close relations, from Homo erectus, which looked quite a lot like modern humans, to Paranthropus boisei, which looked much less so. Each one carried a legacy: vital genetic, behavioral, biological, and geographic information about our shared origins. They were all strands in the interconnected web of humanity.

Today Homo sapiens are the only members of the Homo genus left, but we don’t stand entirely alone. If we zoom out a little to look at our family Hominidae, four genera of great apes remain: us, chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans.

Looking at the numbers, there are approximately 7.67 billion people on the Earth today. In contrast, according to the World Wildlife Fund, the wild chimpanzee population is under 300,000, wild orangutans are fewer than 120,000, and although gorillas are notoriously hard to count, it is estimated there are some 100,000–200,000. Every great ape is endangered—except us.

The tragedy of those numbers is apparent to anyone who cares about conservation. We lose species to extinction every day, driven by economically motivated habitat destruction or unfettered consumerism. Wherever humans go, biodiversity often suffers, and we are everywhere.

Great apes are special because they are the closest remaining threads on that web of humanity, and we can never recover the information they have to share about our origins once they are lost. Apes are uniquely impactful to the field of anthropology, where we researchers look to the past to understand our present. If the desire to preserve biodiversity isn’t enough to save the apes, then unlocking the human story should be a further impetus for their conservation.

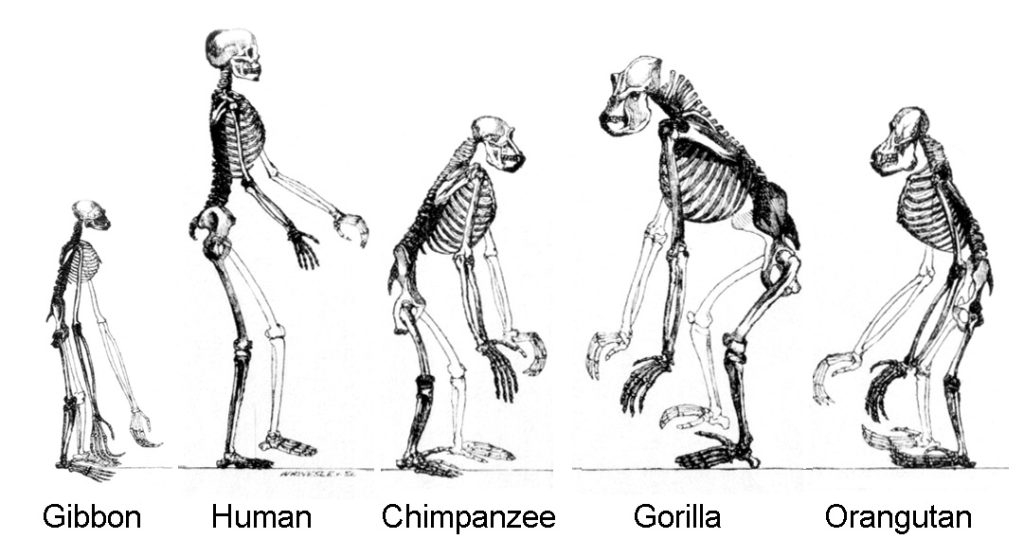

Consider bipedalism: One of the most fundamental things about being human is that we walk upright on two legs. Some anthropologists have even suggested that this feature allowed us to become successful as a species because it freed our hands to carry loads over long distances or make and use tools.

But evolution doesn’t act on a blank canvas. It works on bodies that already exist and move through the world. Because our ancestors started on four legs and moved to the trees, we pay the price for upright walking with lower back pain and less stable joints. When we evolved bipedalism, the advantages of standing on two legs must have outweighed the disadvantages, or it wouldn’t have been successful.

The questions anthropologists want to answer are: When did it happen? How did it happen? Why did it happen?

For hints, scientists turn to two places: the fossil record and our great ape cousins.

Great apes give us a window into our past that no other animals on Earth can provide.

In the fossil record, there is evidence of bipedal features in species such as Orrorin tugenensis (6 million years old) and Ardipithecus ramidus (4.4 million years old). In remains like those of the famous “Lucy,” officially named Australopithecus afarensis (3.2 million years old), it is clear that even after we had been standing on two legs for a while, we kept many features that came from living in the trees. That remains true today. Imagine reaching above your head to grab something out of the cupboard. That is only possible because your shoulder joint originally evolved to help us swing from branch to branch.

Still, fossils are rare, and researchers haven’t found any yet that look like they may be our direct ancestors in the middle of transitioning to bipedality. So, anthropologists turn to the apes.

Orangutans were the first of our great ape relatives to split off from the line that would eventually become Homo sapiens around 13 million years ago. Today they spend more time in the trees than any other great ape and practice a form of locomotion called quadrumanous scrambling, meaning they can use their feet to grasp things, like branches, in the same way as their hands. When hanging out in trees, orangutans will often hold themselves upright by grasping high branches and standing on two legs.

Gorillas were the next apes to split from our lineage between 7 and 8 million years ago. They are the heaviest of the great apes and spend most of their time on the ground. Gorillas use a form of locomotion called knuckle-walking, moving around on all fours on their knuckles rather than the flats of their palms. They have also been observed walking upright on two legs like humans, but because their skeleton is not built to walk that way, it is slow and very energetically costly for them.

The last of the apes to split from us, and thus our closest relatives, are chimpanzees, who diverged between 5 and 6 million years ago. Chimps spend their time in the trees and on the ground, practicing both knuckle-walking and vertical tree climbing, as well as hand-over-hand swinging from branches. When the situation calls for it, they can also be observed walking bipedally on the ground, sometimes even carrying food for their young.

These observations have given anthropologists a way to study the origins of bipedality in a way we just don’t get from looking at fossils. Some researchers believe our ancestors started knuckle-walking on the ground before slowly moving upright sometime between when we split from gorillas and chimps. Others think we started standing upright in the trees around the time we split from orangutans, and the millions of years of selection between us and gorillas or chimps pushed those species in another evolutionary direction. Some have even suggested that it happened after our split from chimps.

Whichever argument wins the day, it’s only possible to develop these lines of thinking because our ape relatives are still here to study. Great apes give us a window into our past that no other animals on Earth can provide. They offer clues about the evolution of so many things that make us human, like language, tool use, and childhood development. They aren’t us, but they aren’t exactly not us, either.

When the apes are gone, so will be an irreplaceable connection to our own past. Without them, we 7.67 billion humans will only be even more alone.