The Mystery of the Corpse in the Burlap Sack

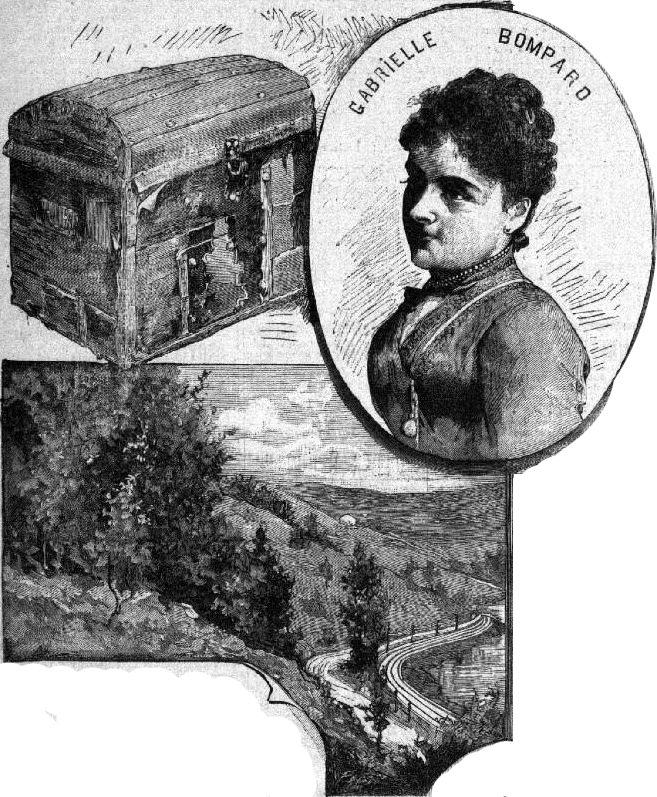

On July 28, 1889, a couple drove a carriage down a remote road about a dozen miles south of Lyon, France. Michel Eyraud, a middle-aged conman, and his mistress Gabrielle Bompard, who was half his age, were looking for an out-of-the-way place to dump their decaying cargo. Eyraud found the perfect spot in the woods near the village of Millery. He opened a large trunk and hoisted a heavy burlap sack into the bushes. A few miles down the road he smashed the wooden chest and threw away the pieces.

Over the next couple weeks the villagers of Millery complained about a horrible odor in the nearby forest. When the stench did not dissipate a village road mender was sent on August 13 to try to find its source. It didn’t take him long. He followed the smell and a cloud of flies to the burlap sack in the bushes. When the road mender looked inside he saw the severely decomposed corpse of a man with dark hair and beard.

A few days later, the broken pieces of the trunk were discovered, and since they were saturated with the rotting smell of death, the police believed the trunk was connected with the corpse in the sack, so the pieces were kept as evidence.

The body was taken to Dr. Paul Bernard, a medical examiner at the morgue in neighboring Lyon, for identification and autopsy, but it was too badly decayed to determine much from the soft tissue. This case was going to require techniques that were just being developed for the field that would become known as forensic anthropology, techniques that rely on the bones of the body to help with identification. Forensic anthropology was in its infancy in 1889, so there were only a handful of scientists acquainted with methods that used skeletal remains for human identification, and Bernard was not one of them.

Meanwhile, the mysterious Millery corpse had caught the attention of the French press, and the grisly story was publicized throughout the country. An assistant superintendent with the Paris police named Marie-François Goron read the articles and had a hunch that the body was that of Toussaint-Augustin Gouffé. Gouffé, a wealthy Parisian bailiff (a legal professional and debt collector) and a well-known womanizer, had disappeared a couple weeks earlier, but the trail had gone cold. Goron was desperate for a lead, and his gut told him that these two cases were connected.

Gouffé was last seen alive with some unsavory characters near his Paris apartment on July 26, 1889. When he failed to show up at home the next morning, his housekeeper alerted his brother-in-law, Louis-Marie Landry, who then reported him missing. Since Goron suspected the Millery corpse was the missing bailiff, he sent Landry to Lyon to identify the body.

Because the corpse’s facial features were bloated and distorted by decomposition, Landry relied on the body’s hair color to make the identification. Since the hair of the Millery corpse appeared to be black and Gouffé had reddish-brown hair, both Dr. Bernard and Landry believed the body was not Gouffé. So the corpse was buried in a common grave at the nearby cemetery.

Goron, however, remained undeterred in his belief that the body was Gouffé, so he traveled to Lyon to see for himself. During his interview with Bernard, the two men got into a disagreement about the corpse’s identity. Bernard thought he would shut down the relentless detective by showing him a sample of the body’s black hair. But Goron grabbed the strands and washed away the dirt and decomposition fluid to reveal that the hair in fact had a distinctive chestnut color.

Since Bernard had missed a key detail of the body’s appearance that was critical to its identification, Goron no longer trusted Bernard’s autopsy findings. Luckily for Goron, there was a well-known practitioner in the field of forensic science nearby— Alexandre Lacassagne (1843–1924. Lacassagne was the head of the department of forensic medicine at the University of Lyon and was familiar with using skeletal analysis to identify human remains. Goron had the corpse exhumed in November of 1889 and took it to Lacassagne for a second postmortem examination.

There wasn’t much soft tissue left on the corpse after months of decay, so Lacassagne looked to the bones for identification and clues to the cause of death. According to Steven Levingston in his book Little Demon in the City of Light: A True Story of Murder and Mesmerism in Belle Époque Paris, Lacassagne measured the long bones and found that the deceased had been about 5 feet 8 inches tall. Lacassagne’s analysis of the wear and tear of the teeth suggested that the man had been about 50 years old when he died. He noticed that an upper right molar was missing, and he saw a deformity in the right knee and heel that looked like a sign of inflammation that would have caused a limp. Lacassagne also found that the thyroid cartilage was broken, indicating that the man may have been strangled.

In the process of identification, forensic anthropologists must compare their findings from a skeletal examination to the antemortem (before death) records, like a driver’s license or a passport. In this case, Lacassagne looked at Gouffé’s military records and talked to his family. Gouffé’s military records and family confirmed that he was 49 years old and was 5 feet 8. His family also confirmed that he walked with a limp. Gouffé’s dentist verified that he had one of his upper right molars removed years earlier. Furthermore, Lacassagne found that hair samples taken from the Millery corpse and Gouffé’s hairbrush matched. Based on this information, Lacassagne concluded that the body belonged to Gouffé.

Goron had a replica made of the foul-smelling trunk found near the body and had pictures of it published in newspapers throughout Europe. Eyewitnesses came forward who had seen Eyraud and Bompard with the wooden chest. People also said they had seen the duo with Gouffé around the time of his disappearance in Paris.

Goron distributed descriptions of Eyraud and Bompard all over Europe and North America in the hopes of capturing them. Gabrielle Bompard turned herself in to the police in France in January of 1890. Then, in May of 1890 Michel Eyraud was arrested in Cuba and extradited.

Bompard told police that she and Eyraud knew Gouffé kept a lot of money on him and wore an expensive ring. So knowing his reputation as a philanderer, they hatched a plan to seduce Gouffé, then rob and kill him.

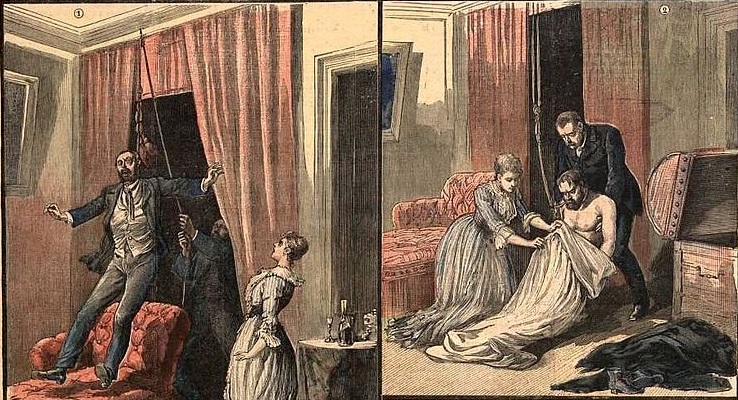

On July 26, 1889, they installed a pulley on a crossbeam in Bompard’s Paris apartment. The plan was to lure Gouffé into her home, then flirtatiously wrap a sash around his neck and connect it to the pulley. Eyraud, who was hidden behind a curtain, was to grab the rope attached to the pulley and haul him upward. Bompard claimed that when the rope slipped Eyraud was forced to strangle Gouffé with his bare hands. Afterwards, they tied the body into the fetal position, put it in a canvas sack, and stuffed it into a large trunk.

Eyraud and Bompard’s murder trial was one of the most notorious and bizarre of its time. Although they were tried as co-defendants, the former couple did not get along in the courtroom. They argued with each other, witnesses, and even the judge. Eyraud claimed that the robbery was Bompard’s idea; Bompard claimed Eyraud hypnotized her into committing the crime. The trial was sensationalized, and spectators packed the courtroom to watch the drama unfold.

Eyraud and Bompard were both found guilty. Eyraud was sentenced to death and sent to the guillotine on February 4, 1891. Bompard only got 20 years in prison for her part in the murder.

The case was one of many in which Alexandre Lacassagne was either an investigator or an expert witness, and over the course of his career he developed many forensic techniques that are still used today. He was the first to observe the link between bullet striations (markings) and the rifling pattern (spiraling grooves) in a specific gun barrel. He pioneered bloodstain-pattern analysis, used tattoos to identify bodies, and used lividity—the post-mortem settling of blood in the lowest part of the body—to estimate the time since death. In fact, Lacassagne’s contributions to forensic science were so significant and wide-ranging that he has been called the “father of scientific criminal investigation,” and the “French Sherlock Holmes.”