How Allocating Work Aided Our Evolutionary Success

In his 1776 book The Wealth of Nations, economist Adam Smith described the “very trifling manufacture” of pins: “One man draws out the wire; another straights it; a third cuts it; a fourth points it; a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head.” Thirteen more steps followed.

By Smith’s estimate, this carefully orchestrated allocation of tasks enabled thousands of pins to be produced each day. In contrast, a lone worker “could scarce, perhaps, with his utmost industry, make one pin in a day, and certainly could not make 20.”

The division of labor increases production in every art, Smith concluded.

Divisions of labor are found across all human societies, whether the members reside in industrialized cities, farming villages, or hunter-gatherer camps.

But no other primate partitions tasks to this extent.

Universal across cultures but distinct from other primates—such a behavior demands my attention as an evolutionary anthropologist. Was division of labor a spark that ignited our species’ evolutionary success? And if so, when in our past did the behavior emerge?

DIVISIONS OF LABOR IN FORAGER SOCIETIES

For most of Homo sapiens’ 300,000-some years on Earth, our species has been hunter-gatherers, meaning people have obtained their food from wild plants and animals. Forager groups have thrived in nearly every imaginable habitat, from humid tropical rainforest to the frigid Arctic tundra.

For the past 14 years, I have conducted research among contemporary foraging populations in tropical Africa and Asia, studying the ways in which people search for, harvest, and process food. These are modern people, of course. But the modern foraging lifestyle can lend insights into how our ancestors found food and water, and how they cooperated while doing so.

From my observations of daily life in foraging societies, one obvious pattern is that people divide labor by age. Children might collect fruit and shoot small birds with slingshots. Knowledgeable and able-bodied adults usually go after challenging resources, such as large prey or dangerous beehives. Older individuals—who still know a lot but are less physically capable—may dig tubers and watch grandchildren.

I have also noticed pronounced divisions by gender among all the hunter-gatherers with whom I have worked. [1] [1] I follow other scholars who define sex as a biological denotation and gender as a “social denotation, often based on biological cues, but shaped by the intersection of social norms and personal expression.” But in the context of division of labor, few studies have distinguished between sex and gender. The divisions are permeable and represent statistical averages: Individuals can deviate from what most members of their gender mostly do. But those gendered patterns, nevertheless, exist.

Cross-cultural studies bear out my impressions: Men tend to hunt large prey and collect honey, whereas women usually go after plants, shellfish, and small animals. Scholars have suggested these differences emerge because women pursue more reliable (lower-risk) foods to consistently provide for their children. Meanwhile, men can afford to spend a day tracking large game—even when it means sometimes returning empty-handed.

In foraging societies, women also do most child care, laundry, and gathering of fuel and water. Men typically attend to construction work and maintenance of nets, houses, boats, and other technologies.

Much of these data come from ethnographies and reports written from the 1800s to the present-day. Especially for some earlier works, the researchers, most of whom were men, documented what interested them, which often did not include “women’s work.” Many of the accounts are qualitative and were written by Europeans as part of colonial expansion and rule. Despite these issues, the gendered patterns appear to be universal and thus likely real.

THE BOONS OF DIVIDING LABOR

Foragers may not be specialists in the manner of pin manufacturers, but the advantages of dividing labor are much the same.

Hunting and gathering requires years of hard-earned skill. Conducting fieldwork in Malaysia as a fit male in my 30s, I was told by my forager Batek friends that I was incompetent at gathering—and it was simply assumed I would fail as a hunter.

While I proved deficient at hunting and gathering, no Batek individual fully masters both. The expertise required for different foraging tasks favors the evolution of some degree of specialization.

“By allocating tasks, ancient humans supercharged their cooperative potential.”

For our ancestors, it would have made sense for some individuals to gain the skills needed to find and dig up plants, while others learn to hunt. Women would have provided the crucial carbohydrate base through plant foraging. Men would have then been freed to attempt risky hunting. Everyone would have benefited if food was widely shared.

As my colleagues and I showed in a recent study, hunter-gatherers can acquire more calories in less time compared to other great apes. Like with Adam Smith’s pin manufacturers, divisions of labor make this possible. The fact that all studied contemporary hunter-gatherer societies around the globe have gendered divisions of labor could be evidence of its success as an evolutionary strategy.

DIVIDED BUT FLEXIBLE

Gendered divisions of labor appear in all studied forager societies. But the divided work is remarkably flexible and never absolute. Sometimes women hunt, and sometimes men gather. As I saw with Batek hunter-gatherers, men frequently collect rattan—a climbing palm often used in furniture construction—even though it’s a plant. Similarly, Batek women sometimes hunt bamboo rats by smoking them out of trees and whacking them with machetes.

Looking beyond the Batek, my students and I reviewed written descriptions related to women’s hunting in 64 societies. We found that across cultures, women tend to hunt relatively immobile and easy-to-catch game—creatures like small mammals, lizards, and birds. In contrast, men stalked larger prey over long periods far from camp. It’s likely that women avoid this sort of hunting because of the competing demands of child care, food preparation, and other camp-based tasks.

Recently, some scholars have argued that because women can and do hunt in foraging societies, gendered divisions of labor haven’t existed widely across cultures or deep in our evolutionary past. Some have suggested the behavior only emerged more recently due to the influence of patriarchal agriculturalists and colonial administrators.

While this topic remains hotly debated, in my view, these recent arguments don’t stand up to the evidence.

Communities where I work contradict the notion that women hunt except when prohibited by patriarchal social norms. In Batek society, women enjoy high levels of equality with men. In fact, the most famous ethnography about them is called The Headman Was a Woman: The Gender Egalitarian Batek of Malaysia. Nevertheless, they still divide work by gender lines, proving that divisions of labor are not necessarily linked with patriarchy.

In some societies, women happily forgo hunting as a regular activity. Anthropologist Richard Lee, who worked with the Ju/’hoansi people in Southern Africa, never got the impression women were bothered by the fact that they did not hunt. In the late 20th-century, anthropologist Helga Vierich was told by Ju/’hoansi women: “Hunting is boring and unreliable. Let the men do it!”

LOOKING BACK

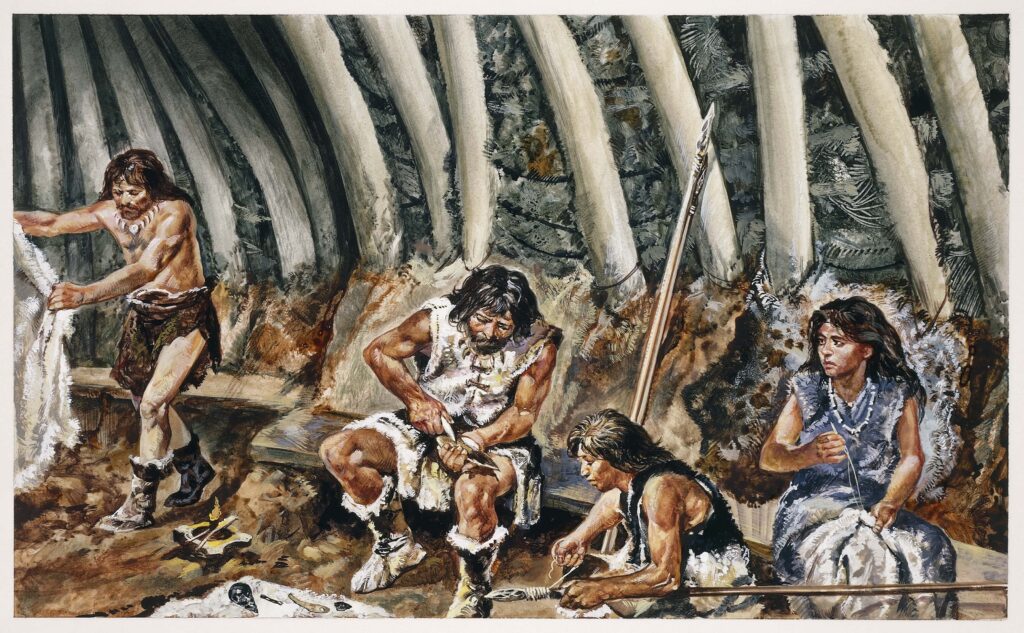

No one knows when gendered divisions of labor emerged in human evolution. It may have been as early as 300,000 years ago when H. sapiens appeared, or perhaps even longer ago. Researchers have proposed that as far back as 2 million years ago, human ancestors began to focus on high-reward but hard-to-get foods like underground tubers and, later, large game. In this context, it would have been fruitful to divide labor so individuals could master specialized skills.

Fossil evidence can help narrow the possibilities.

Let’s consider the sexual division of labor specifically (here we focus on sex because gender is difficult to reconstruct from fossil evidence). In one study, University of Tübingen paleoanthropologist Judith Beier and colleagues examined skulls from Neanderthal and H. sapiens who lived roughly 80,000 to 20,000 years ago. For both species, the scientists found more head injuries among the male skulls than the female ones. Perhaps these injuries indicate ancient males undertook more dangerous activities such as big-game hunting and warfare.

Another line of evidence: During life, bones morph their thickness and shapes in response to regularly repeated activities. Also, teeth wear down in distinctive ways when used like a third hand to grip materials while crafting. Analyses have found consistent differences in these properties between male and female fossils from the Paleolithic. The pattern suggests different sexes performed different tasks—although modern researchers can rarely infer exactly what those tasks were. These interpretations are also complicated because bone density varies in response to other factors including infections, the number of children one has birthed, and genetics.

This is why modern foragers offer such an important reference point. To meet the demands of daily life, different genders and age groups focus on distinct tasks—at least, that is the case for every studied contemporary forager society.

Like ancient forager societies, modern forager societies face the same general constraints of 24 hours in a day with challenging and knowledge-requiring work to do. It’s reasonable to assume ancient peoples struck upon the same strategy as foragers today: splitting work among their group members.

Our hunter-gatherer ancestors were not dividing labor like ants or workers in an industrialized pin factory. But they were doing something similar. By allocating tasks, ancient humans supercharged their cooperative potential. This is a legacy that we, for better or worse, live with today.