Fighting for Justice for the Dead—and the Living

WHEN A PERSON DIES, forensic anthropologists often help recover the body, estimate or establish their identity, aid in determining manner of death, and even testify in court. Through this work, drawing on knowledge from human skeletal biology, anatomy, and archaeology, we often confront the immense social and racial inequalities that can play a role in the circumstances of one’s death.

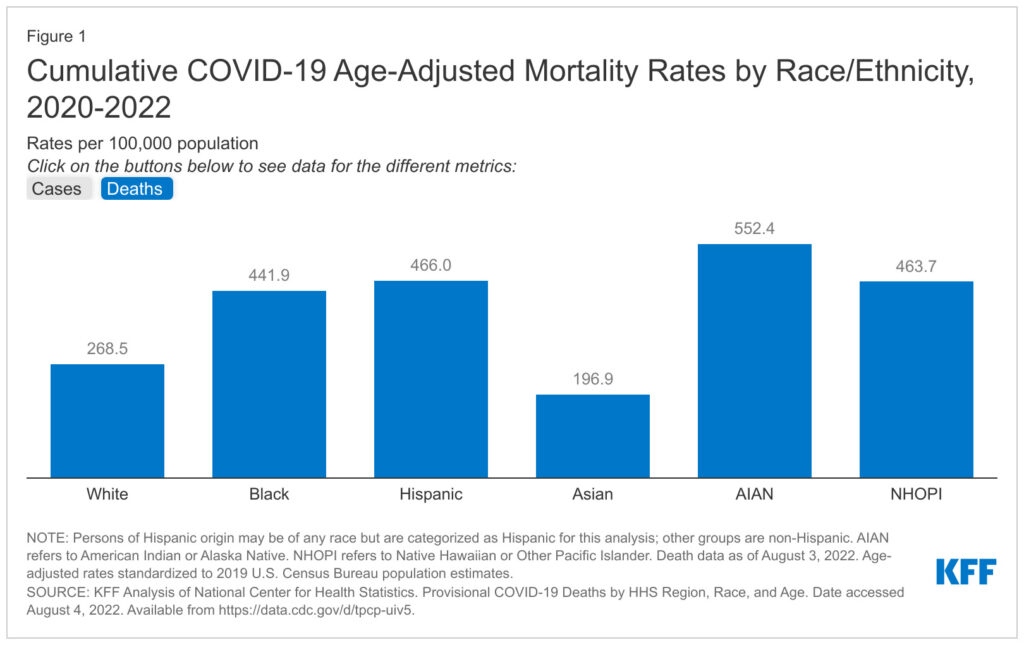

In our work, we have witnessed the effects of societal injustices such as health and class inequities and racism for decades, but they certainly came to the forefront in March 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic first hit the United States. We saw how Black Americans were more than twice as likely to die from COVID-19 compared to White Americans and had 4.7 times higher rates of hospitalization for the virus. The pandemic also took a toll on other historically marginalized groups: For example, the annual rate of death by suicide among elders over the age of 85 in Clark County, Nevada, increased by 14 percent across the pre- and post-pandemic periods, according to research in forensic anthropology.

Many of the deceased with whom forensic anthropologists work were considered marginalized and highly vulnerable in life. We strive to ensure that such harms do not extend into death through erasure of identity or lived experience. As public-health adjacent death care workers, we are uniquely positioned to serve as advocates for the dead and—we contend—the living. Yet, while most of the institutions that support forensic anthropologists have failed to center advocacy as a fundamental part of our work, we believe we can no longer stay silent to injustice.

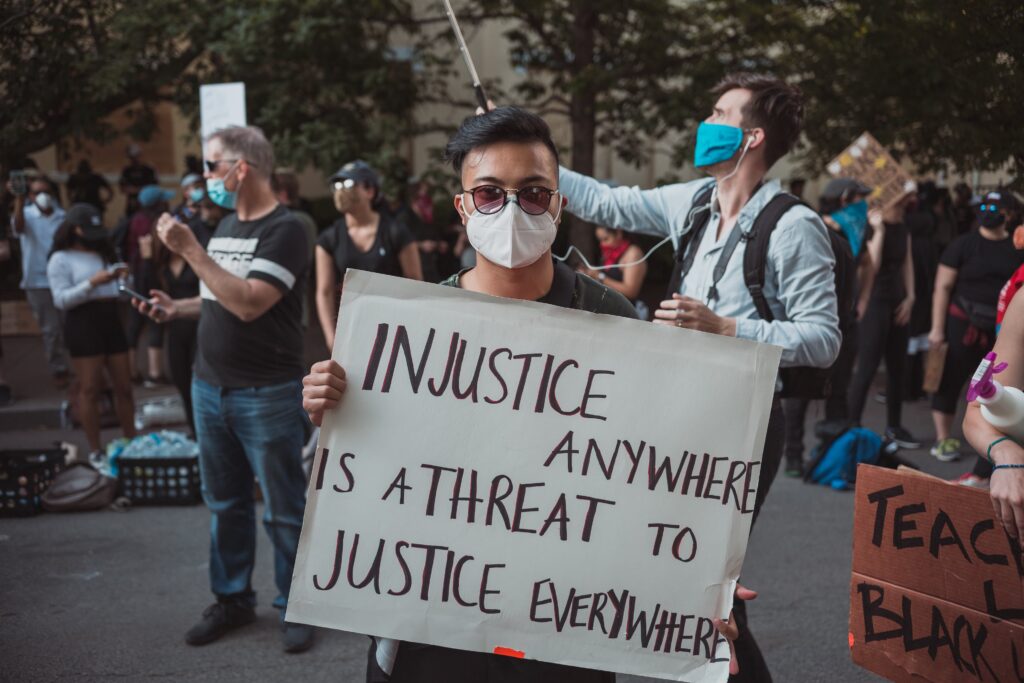

In February 2021, amid climbing COVID-19 death rates and heightened global attention on police-related deaths of Black Americans and on the Black Lives Matter movement, over 150 forensic anthropologists gathered for an urgent virtual meeting to discuss diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) issues in the American Academy of Forensic Sciences (AAFS). This is the flagship U.S. forensic science organization that includes anthropologists, pathologists, toxicologists, dentists, nurses, and other forensic scientists. When some members called on the AAFS to outwardly oppose police brutality, AAFS leadership took a decidedly anti-advocacy/activism stance to pressing social issues in favor of unbiased “objectivity”—even though these issues intersect with the work that forensic scientists, and especially forensic anthropologists, do, and the fact that science is inherently subjective.

As active AAFS members and LGBTQIA+ and ally anthropologists, we struggled to make sense of an anti-advocacy stance that prioritizes aspirations for objectivity and neutrality in a highly unjust and inequitable world. The AAFS did not issue a formal statement on its anti-advocacy position. However, some members speculated that the AAFS, which often works closely with more conservative-leaning police departments, did not want to upset its more conservative members and those who think that science and scientists are, or should be, wholly objective and unbiased.

In the wake of that 2021 virtual meeting, we were compelled to speak out about the roles of advocacy and activism in forensic anthropology. This led the four of us, along with our colleagues, to author an open-access article on how advocacy and activism make for stronger science. Our advocacy work extends to both the living and the dead by discussing some of the unique and intersecting societal issues faced by marginalized communities, including Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC), migrants, and LGBTQIA+ individuals.

THE MYTH OF OBJECTIVITY

Forensic anthropologists often hear that engaging in advocacy (supporting voices, identities, and positions of others) and activism (specific, direct, and sometimes radical action to fight injustices) threatens our ability to stay objective and unbiased. Participating in protests, sit-ins, walkouts, or marches is deemed problematic, but even “liking” an anti-racist and anti–police violence social media post is said to jeopardize our individual and collective roles as experts in courts of law. By extension, these actions could reveal biases and prejudices that contradict our roles as objective and unbiased scientists and may result in miscarriages of justice if our testimony is discounted.

But forensic anthropology testimony is only one aspect of our job. In fact, many of us rarely, if ever, testify. And, when we do, the testimony is generally limited to speaking about the trauma observed on a skeleton or the methods used to scientifically link the deceased to a known person.

Therefore, the hypothetical criticism that a minority of forensic anthropologists may receive from the prosecuting or defense attorneys for being perceived as advocates or activists should not set the standards for the field. We argue that wholesale allegiance to the criminal justice system, which often goes unquestioned as the “neutral” stance, represents a biased perspective that can jeopardize science in the interest of closing cases.

We believe that a stance against advocacy and activism is flawed and unrealistic.

Scientists are not and cannot be wholly objective or unbiased. We are humans asking questions about the world around us. In fact, scholarship demonstrates how propagation of the objectivity myth is damaging to science and is a product of White, cisgender, abled, and heterosexual privilege. “Pure objectivity” is a fallacy: Lived experience, cultural contexts, and the particularities of each case all impact and inform the work of forensic scientists.

This myth of objectivity can also have substantial effects in the courtroom, where jurors expect experts and their science to be infallible; as we have seen from the numerous cases overturned due to faulty forensic evidence or methodologies, failure to acknowledge and control for our own subjectivity can have devastating consequences for victims’ families and those who have been falsely accused.

Further, the field of forensic anthropology has thankfully grown increasingly diverse, comprised of individuals from activist-oriented and marginalized communities who may share identities with the deceased. It is therefore unreasonable to expect scientists to remain silent when we see harm, including racialized police violence, life-threatening border policies, and violent anti-transgender legislation intensifying within our own communities and those we serve.

ADVOCATING FOR THE DEAD—AND THE LIVING

Advocacy and activism are nothing new to anthropology. Cultural anthropologists, archaeologists, and biological anthropologists have included these actions in their scholarship for decades.

We argue that staying neutral does not make science better, and ignoring advocacy and activism goes against anthropology’s mission to deeply understand and improve lives. Research focused on activism challenges unfair and inequitable systems and helps us reduce harm in the communities we serve.

Consider the life of William Montague Cobb, one of the only Black biological anthropologists during the mid-20th century, who was also an avid scholar-activist. Cobb advocated for increased health care for Black Americans, boycotted organizations in racially segregated cities, and was active in civil rights organizations—all while producing research that countered the myth that Black people were biologically inferior. Cobb’s overt advocacy and activism serve as an example of how such engagement may not be a choice for some. His activism was inseparable from his scholarship, and our field benefited greatly from his work.

Individuals from marginalized communities serve as advocates and activists as they navigate spaces that were not made for their success. For them, advocacy and activism are an added demand for entry into a majority White, cisgender, abled, and heterosexual profession such as anthropology. We understand that not every forensic anthropologist can participate in overt activism. Some are employed in governmental organizations or in jurisdictions that may limit their political engagement. Yet when considering the advocacy-activism spectrum, working within the realms of education, casework, and research presents new possibilities.

Gone are the days where we, as a discipline, can afford to be quiet when confronted with inequities that lead to death.

In classrooms, we can present class lectures and lead discussions on how intersectional identities relate to skeletal variation and positive identification—a topic only recently appearing in standard coursework and education. Instructors can also work toward diversifying syllabi to uplift marginalized voices, actively mentor students and peers, or even join campus or local protests.

In our casework, forensic anthropologists can use bioculturally appropriate terminology to explain human variation, including discussing the processes and limitations of ancestry and assigned sex estimation with law enforcement. We can also curb harmful language disparaging the dead often used by colleagues, students, or law enforcement, and educate the medicolegal community and policymakers on human variation and accurate terminology. All of this is not only a form of advocacy, but also just good evidence-driven science.

And in research, we can implement inclusive citational practices to uplift marginalized voices, engage with descendent communities throughout the research process, diversify the theoretical frameworks used to guide research, develop and implement ethical guidelines and training for human skeletal biology research, collaborate with diverse scholars, call for a diversification of journal editorial boards, and conduct or encourage research informed by identities and lived experience.

We can also work with colleagues to change inequitable practices in professional organizations and confront and change systemic barriers to entering the field. This includes consideration of financial burdens, immigration status for employment purposes, and the recurrent microaggressions experienced by people from a variety of identities. Forensic anthropologists can also find opportunities to retain and strengthen DEI initiatives in professional organizations and universities, use forensic data to advise on policy changes, advocate for the individuals who provide the data used in our research, and, if safe, be professionally out and visible if from a marginalized identity, while fostering truly inclusive and safe spaces.

Moreover, as targeted attacks on science, DEI initiatives, health care, and the communities we belong to and serve intensify under the current political administration, overt and covert advocacy and activism efforts will be crucial to maintaining and restoring human rights for the living and dead.

In a 2023 Journal of Forensic Sciences editorial, then AAFS President Laura Fulginiti stated: “As human beings, we would be viewed as callous and indifferent were we to express nothing at brutal death; however, as forensic scientists, our responsibility is to do just that.”

We emphatically disagree and draw attention to the falsehood that forensic scientists must be a special class of unfeeling and indifferent people. Gone are the days where we, as a discipline, can afford to be quiet when confronted with inequities that lead to death, further marginalization of the dead and the living, and our involvement in forensic cases. Nor should we be quiet when confronted with anti-science legislation, human rights violations, and attacks on DEI efforts that have strengthened science. It’s time to leverage our unique perspectives, experiences, skill sets, and identities to care for both the dead and the living.