The Battle to Protect Archaeological Sites in the West Bank

SIGNS OF LOOTING appear everywhere at archaeological sites across the West Bank. Amid Israel’s ongoing war in the region, subsistence looters—people seeking personal profit due to enforced impoverishment—come to these archaeological sites in pursuit of valuable objects. Trekking for thousands of hours through these sites, I have seen the destruction of critical remnants of ancient structures, the obliteration of numerous mosaic pavements and subterranean rock-cut features, and the demolition of incalculable layers of cultural history.

As a Palestinian archaeologist living in the West Bank, I felt it was imperative to survey archaeological sites to assess damage incurred since October 8, 2023, when Israel’s most recent war against the Gaza Strip began. The subsequent spread of violence into the West Bank has inflicted extensive infrastructural damage, including to archaeological sites and historic monuments integral to the cultural and historical identity of the Palestinian people.

Beyond bombings and other military activities, curfews and checkpoints have severely hindered the efforts of the West Bank’s Palestinian archaeologists, heritage organizations, and security personnel to access, monitor, and safeguard these vulnerable sites. As a result, the risk of antiquities looting, and other forms of degradation, has increased due to the high exposure and limited oversight of many previously protected sites. Looting has always been an issue, but the recent escalation of hostilities by Israel against Palestinians has led to an increase in antiquities looting, as tens of thousands of unemployed people struggle to meet their most basic needs.

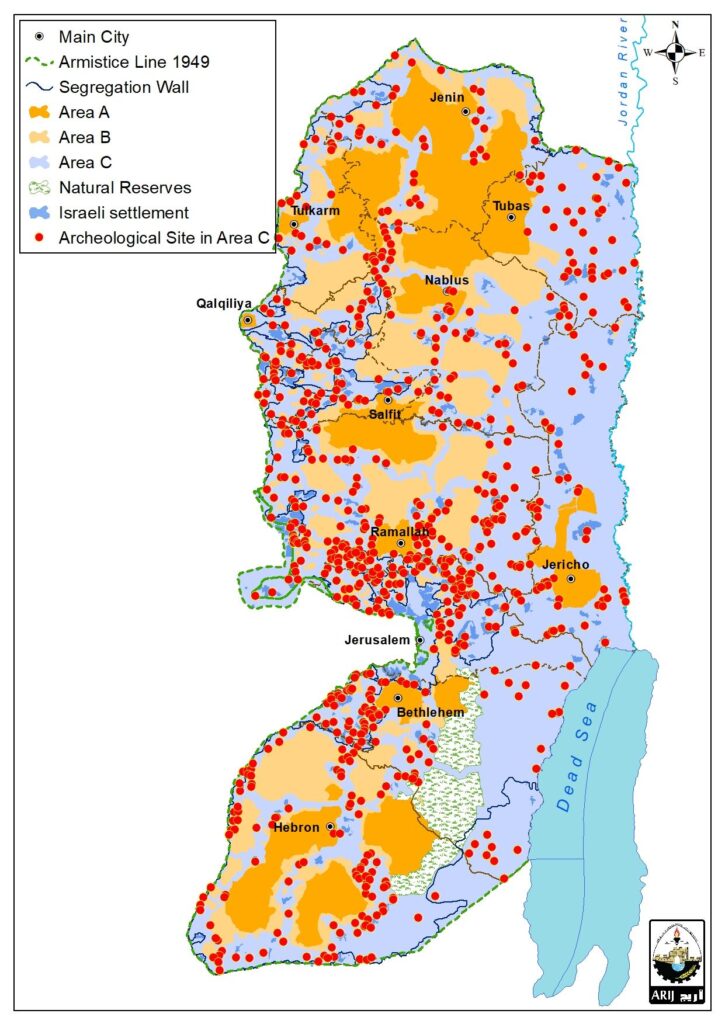

Intensified Israeli military presence and settler violence in the West Bank also continue to pose substantial risks to our safety and security in the region. Despite these risks, I have worked urgently over the last 12 months with my students and personnel from the Palestinian Tourism and Antiquities Police Department to survey approximately one-fourth of the West Bank’s archaeological sites amid ongoing hostilities. In doing so, we were able to accurately map the spatial distribution of looting pits within hundreds of sites—offering critical insights into the archaeological areas most at risk of destruction.

Looting pits are often dug haphazardly, with total disregard for a site’s archaeological significance. Pits dug with hand-held tools appear irregularly shaped—circular, oval, or shallow bowls—and range from 0.5 to 10 meters wide and 0.4 to 7 meters deep. Pits dug with metal detectors, often used for locating coins and other metal objects, frequently make shallow, bowl-shaped pits, while those excavated with heavy machinery are substantially larger, covering areas between 25 and 1,500 square meters and reaching depths of up to 2.5 meters.

Overall, our survey reveals widespread evidence of looting at 309 out of 440 sites we visited in the West Bank. In total, we documented 2,976 new looting pits.

INSIDE KHIRBET WILI SHABBUNI

Here is an example of our work at just one ancient site.

Khirbet Wili Shabbuni, an ancient archaeological site northwest of Jerusalem near the historic center of Deir Ibzi’ village, provides commanding hilltop views of the surrounding areas in all directions. Between February and September 2024, my team and I conducted four visits to identify and document new damage caused by antiquities looters or other human activities.

People have inhabited Khirbet Wili Shabbuni since the Hellenistic period beginning at 332 B.C. through the Roman, Byzantine, Early Islamic, Crusades, and Ayyubid-Mamluk periods, until about A.D. 1517. The landowners of the khirbet (ruins in Arabic), along with residents from nearby villages, maintained regular visits to the site for religious and agricultural purposes over the past several centuries. This persisted until the 1980s when socioeconomic and religious changes led to less engagement with the site.

The remaining architectural features include a Byzantine monastery, an Islamic sacred shrine, ritual baths, cisterns, several burial caves, natural caves, bowl-shaped basins, an olive oil press, and numerous dry-stone terrace walls. The best-preserved building complex is about 24 by 30 meters—larger than a basketball court—featuring several rooms and corridors, with stone walls that stand up to 2.6 meters tall.

During the four visits, my team and I documented widespread evidence of looting. In one instance, pillagers had excavated through a mosaic floor. Looters also caused significant damage to the Byzantine monastery, partially or completely dismantling long sections of its walls, leaving piles of stones scattered nearby.

My team and I carefully documented a total of 45 surface cuts, numerous dismantled ancient walls, and a few pillaged rock-cut subterranean tombs. About 82 percent of looting pits were left fully exposed, while the rest were partially backfilled or concealed under dry branches. It is worth nothing that Khirbet Wili Shabbuni stands out as one of the only sites with relatively minimal plundering and looting. In many other locations we surveyed, up to 70 percent of the total site area was destroyed.

SOARING DEMAND FOR ANTIQUITIES

Historic Palestine is among the world’s most archaeologically significant regions relative to its size. It contains approximately 35,000 archaeological sites and historical monuments, with more than 12,000 situated in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, and the remainder within the borders of present-day Israel. The archaeological heritage of the West Bank includes 1,944 archaeological sites, 10,088 historical monuments, and 50,000 traditional buildings.

Archaeological sites targeted by antiquities looters during the past 12 months range from the Neolithic (9650 B.C–4500 B.C.) to the Ottoman-Turkish periods (1516–1917). But looters predominantly focus on sites from the earlier periods, indicating an awareness of black-market dynamics. Material culture from the Roman period, for example—especially objects associated with the ancient Jewish communities in Palestine—is in high demand. Looters often target these highly coveted objects for their historical and religious significance in the region.

Demand for valuable objects has long posed a threat to Palestine’s cultural heritage. Since 1967, approximately 8.4 million archaeological objects were looted and trafficked through international markets and collectors via Israel as an export hub, irreversibly disconnecting them from their original cultural contexts. But with the recent increase in unemployment, looting has intensified.

Prior to October 2023, Israel used to permit approximately 160,000 laborers from the West Bank—about 20 percent of the total Palestinian workforce—to work within its borders. These workers contributed an estimated US$3 billion annually to the Palestinian economy, representing nearly 13 percent of the GDP. This arrangement helped contain West Bank unemployment to approximately 14 percent.

But since October 2023, the Israeli government has prohibited most workers from returning to their jobs in Israel, skyrocketing West Bank unemployment levels to 35 percent. Now facing severe economic hardship, many of these individuals have resorted to looting archaeological sites in search of valuable objects for personal income.

“LOSS OF HOPE”

In villages near Khirbet Wili Shabbuni, I spoke with several residents about why they had participated in antiquities digging.

“With the loss of hope comes a descent into despair, hardship, and instability,” said one 59-year-old man who asked to remain anonymous. The father of four and grandfather of seven noted that he had lost his permanent employment in Israel during the third week of the ongoing hostilities on the Gaza Strip and the West Bank.

“Despite persistent efforts over the past 10 months,” he said, “I have been unable to secure a stable income within the Palestinian market.” He added, “While you characterize my actions as looting, I view them as a necessary means of survival.”

Over a period of six months, the man said he participated in diggings at five archaeological sites near his home, including Khirbet Wili Shabbuni, and discovered valuable objects. He worked with a group of four, alongside other groups, using a metal detector to facilitate their efforts. They dug over 10 pits at Khirbet Wili Shabbuni, most of which they later backfilled, he said, though they left two open to resume work later.

“Our findings at this site included numerous pottery sherds, five complete pottery lamps, a pottery bowl, a glass bottle, and approximately 25 coins,” he explained, “which we collectively sold to a middleman from the Hebron governorate for US$850.” They had not uncovered highly valuable items at Khirbet Wili Shabbuni, unlike at other sites.

PALESTINIAN CULTURAL HERITAGE UNDER THREAT

Antiquities looting often intensifies during periods of political conflict, unrest, and instability. During violence, people can exploit the chaos and disorder to loot and sell their finds on the black market. Over the past few decades, looting has escalated to such unprecedented levels in Palestine due to loss of control of these sites through a range of Israeli laws and regulations that have rendered them even more vulnerable to looting and neglect. Scholars have described this destruction as part of Israel’s “cultural cleansing,” defined as the intentional, systematic obliteration of a targeted group and its cultural heritage, aimed at erasing not only the people but also all tangible traces of their existence.

It’s not just looting that poses a threat to Palestinian cultural heritage. Hamdan Taha, the former deputy minister of the Palestinian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, has asserted that Israel’s ongoing war in Gaza amounts to cultural genocide. Despite international treaties intended to protect heritage during war, according to Taha, the Israeli Defense Forces have demolished or severely damaged hundreds of archaeological sites, historical monuments, cemeteries, museums, libraries, public buildings, and over 100,000 archaeological artifacts spanning various historical periods.

Since 2002, Israel has assumed control of over 4,500 archaeological sites in the West Bank, including 500 major ones, primarily through the construction of the separation barrier and the establishment of Israeli-occupied settlements in the West Bank. The control exerted over Palestinian archaeological sites has significantly restricted Palestinian engagement in the exploration and documentation of our own history, impeding our capacity to leverage these sites for tourism development and associated economic opportunities.

In July 2024, Israel passed a bill that expands the Israeli Antiquities Authority’s jurisdiction across the West Bank, restricting Palestinian efforts to explore, promote, and protect our cultural heritage. In essence, this measure reestablishes conditions for these archaeological sites reminiscent of the period between 1967, the year Israel began occupying the West Bank, to 1994, when the Palestinian Authority was established. The bill passed a preliminary reading with majority support from 38 coalition and opposition members, while 27 members voted against it.

And in November 2024, Israel’s Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich announced directives to prepare for the annexation of the occupied West Bank in anticipation of U.S. President-elect Donald Trump assuming office in January 2025. Smotrich stated: “I have directed the start of professional work to prepare the necessary infrastructure to apply Israeli sovereignty over Judea and Samaria.” These policy shifts further constrain Palestinians’ capacity to safeguard cultural heritage, leaving numerous sites susceptible to looting, destruction, and loss of historical context.

Palestinian archaeologists are now grappling with a perplexing contradiction: International organizations dedicated to cultural heritage protection often emphasize the importance of safeguarding heritage for future generations. Yet these same organizations often fail to take timely and adequate measures to address these violations in real time. Without strong support to mitigate these impacts, Palestinian archaeology risks becoming a fragmented legacy—a heritage reshaped by competing narratives and severed from its community.