How Volcanoes Destroy and Nurture Societies

The explosion must have been deafening. Clouds of black and gray likely erased the horizon as the earth and sky thundered violently. As smoldering debris rained down on the Ecuadorian coast, having been ejected from a volcano far to the east, the Jama-Coaque I peoples salvaged what they could of their corn, chilies, and beans. Within hours, ash choked off the river that had swept down from the high Andean mountains, watering their fields for generations. The land became foreign and inhospitable, with little remaining food and even less clean water. So they left, abandoning their ancestral homeland for over three centuries before returning.

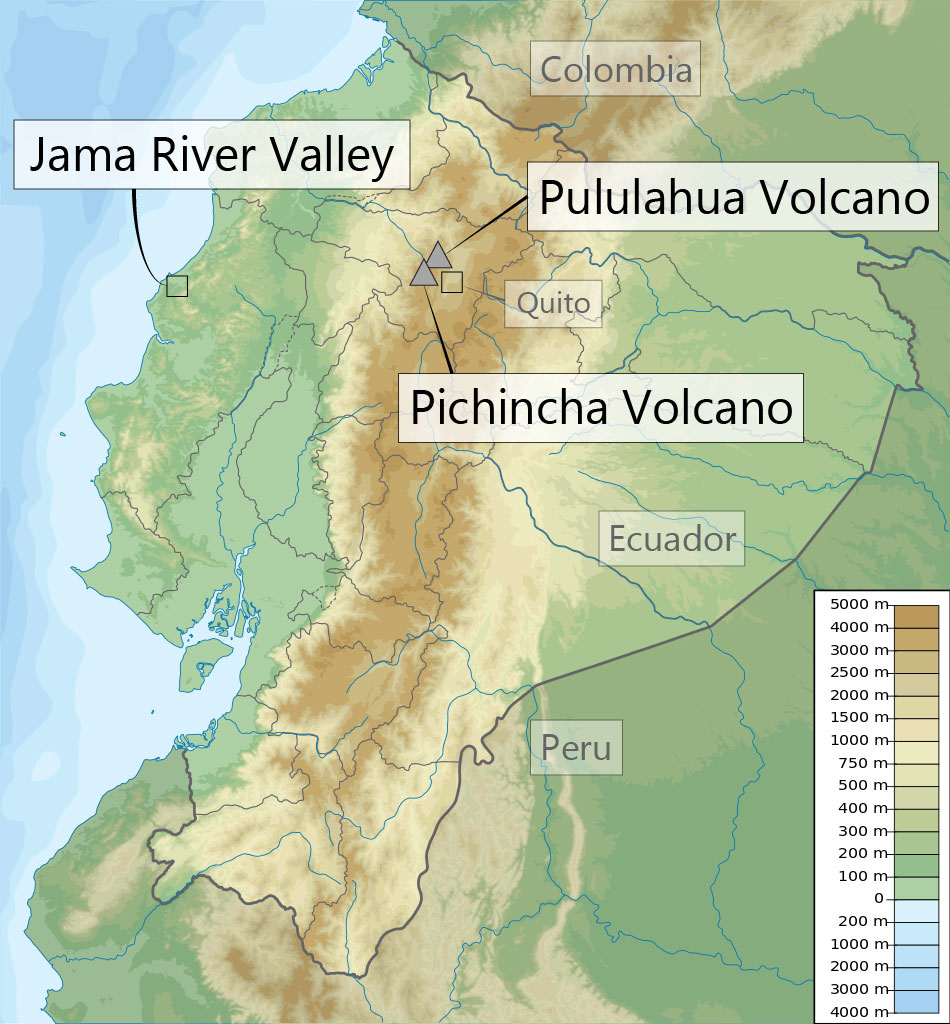

For anicent communities like the Jama-Coaque I, who lived to the west of more than 30 active volcanoes in the Ecuadorian Andes, survival depended on negotiating the ever-present volcanic threat. When this community left their settlements in the Jama River Valley after Pichincha’s eruption in A.D. 90, the event left an indelible mark on their cultural memory. Like other groups of agriculturalists, hunter-gatherers, and fishers that had lived in what is now Ecuador for over 10,000 years, the looming menace posed by the Andean volcanoes was woven into the fabric of their history.

But the danger presented by this string of volcanoes wasn’t always destructive. Volcanic activity may have energized rapid cultural and political developments in the chiefdoms of northwestern Ecuador as early as A.D. 420, according to archaeologist James Zeidler from Colorado State University.

That’s when the Jama-Coaque II peoples (descendants of the Jama-Coaque I) resettled the Jama River Valley—but with hard-won wisdom. While unpredictable eruptions continued to threaten their food security, these returning communities relied on the knowledge passed down by prior generations living under the same conditions to create new tools and strategies. These paved the way for their emergence as one of the most complex cultures in the region until the rise of the Inca Empire.

For more than 6,000 years, the Jama River Valley has supported a diversity of agricultural communities. The Jama River carves its way through northwest Ecuador’s Manabí province, from the steep Andean foothills to the Pacific Ocean some 75 kilometers away. Where the river spreads out along the coastal lowlands, the Valdivia culture—one of the earliest to settle in the region—established a community around 3600 B.C. Now known for developing some of the earliest pottery in South America, the Valdivia peoples thrived in this area for close to 2,000 years, cultivating beans, corn, cotton, and chili peppers.

But around 1880 B.C., disaster struck when Pichincha, a 4,784-meter volcano, discharged a cataclysmic eruption: Ash, lava bombs, and blistering gases shot about 10 kilometers into the stratosphere. The impacts of this intense eruption forced the Valdivians to abandon their villages and farms; the Jama River Valley remained uninhabited for almost six centuries.

For about 2,000 years after this massive eruption, this cycle of human colonization and cultural development followed by a volcanic eruption and forced abandonment would repeat in the Jama River Valley. In 467 B.C., the massive Pululahua eruption cut short the Chorrera culture’s stay—and then over five centuries later, the Jama-Coaque I were similarly forced to flee the region.

It’s not surprising that premodern societies were vulnerable to a variety of impacts from volcanic eruptions, as many communities are still today. What is surprising, however, is what happened when the Jama-Coaque II peoples returned to the Jama River Valley in the fifth century. They began building towns and ceremonial centers along the same river channel their ancestors had been forced to abandon. Unlike those who came before them, the Jama-Coaque II peoples developed a diversity of survival strategies: New agricultural practices, an enhanced propensity for warfare, and large-scale, centralized food storage emerged over the subsequent generations. As Zeidler writes, “Andean volcanism is of critical importance in understanding these social changes.”

How societies cope with the unpredictability of volcanic eruptions depends on how they organize themselves. The Valdivia and Chorrera cultures, for example, were relatively small-scale communities that lived in settlements dispersed across the valley. While they had been growing domesticated crops for millennia, their reliance on floodplain agriculture (the cultivation of crops along annually inundated river banks) left them particularly vulnerable to volcanic ash clogging the river system and killing their crops. Food would become scarce, and emigration was the only viable solution.

The Jama-Coaque II peoples, on the other hand, secured their food supplies in anticipation of future volcanic eruptions by diversifying their nutrient sources. They developed a novel agricultural regime involving forest management techniques that created a patchwork of open habitats in what was naturally a forested environment. By limiting the complete regrowth of dense forests, they attracted a variety of wild plants and animals to open and forested habitats. Larger open spaces also meant farmers had more land to grow their crops; they didn’t have to solely rely on floodplain agriculture. These peoples’ innovative techniques for increasing the availability of both wild and domesticated plants and animals made them much more resilient to the potential damage wrought by volcanic eruptions.

Yet a more robust food base was not enough to withstand all of the threats posed by unpredictable eruptions. The Jama-Coaque II peoples had to survive in the valley for the long term. One of their strategies for anticipating the hardship, according to Zeidler, was to begin constructing large, bell-shaped storage pits in the ground. The size of the pits shows that they served as insurance against bad harvest years and also indicates to archaeologists that the food supply was meant for more than one household.

These communal storage pits also show that significant political changes occurred within the Jama-Coaque II society. To successfully collect and redistribute communal food reserves, people had to live in more densely populated, interconnected communities. The communal nature of these storage pits also suggests some level of centralized authority and control over the redistribution of food resources.

Evidence for the rise of a centralized authority can also be seen in other, more violent aspects of the Jama-Coaque II culture. Institutionalized warfare and raiding became part of everyday life, likely even taking on a ritual significance. Ceramic effigy vessels from this period show fierce warriors in full battle regalia displaying trophy heads, some of which appear to be shrunken.

In combination with the new agricultural practices and communal storage facilities, increased raiding and warfare provided the Jama-Coaque II communities with a powerful suite of strategies for maintaining food reserves in the face of volcanic threats.

In effect, the Jama-Coaque II peoples learned from the lessons of the past. In anticipation of future volcanic fallout, they dug into the toolbox of their cultural memory and successfully implemented what they found. The knowledge they gained after generations of experimentation allowed these communities to develop strategies that staved off the threat of potential volcanic eruptions.

While volcanic eruptions are often violent, destructive events, they are likewise uniquely capable of creation. For the Jama-Coaque II peoples, such events helped inspire a complex, interconnected, and warlike society that ruled the northern Ecuadorian coast for approximately 1,000 years.