Treasure Hunters Pose Problems for Archaeologists

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished under Creative Commons.

THERE ARE ANCIENT PIRATES and modern treasure hunters. They are separated by more than 200 years of history, differences in available technology, and types of sponsorship that keep them afloat—the former sailing for a country and the latter protected by a company. Even so, they seem to have the same objective: the gold and silver of the Spanish Empire.

On October 5, 1804, the frigate La Mercedes came to the end of its journey at the bottom of the sea near Cape of St. Mary at the south of Portugal. A surprise attack by the English wiped out the fleet, which was about to reach its destination. At the time, the two nations were at peace. However, that didn’t matter much to the British Royal Navy.

The tides and the fish were the silent guardians of the treasure, which remained with the sunken Mercedes for more than two centuries. That is, until its discovery was announced with great fanfare in 2007.

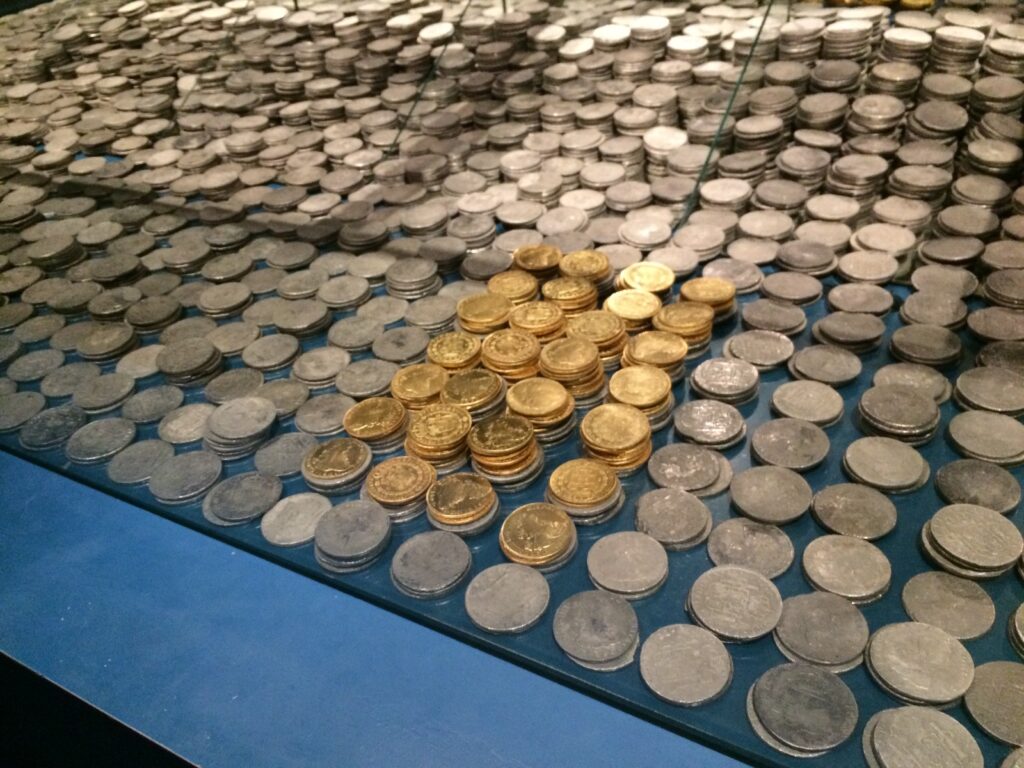

Since 1999, electric lights and robotic submarines had been periodically disturbing the peace of the seabed in secret. The company Odyssey Marine Exploration was sweeping the bottom of the sea in search of the wreck, even though this was a potentially delicate archaeological site. It found its target: almost 600,000 silver and gold coins minted in Peru during the time of Charles IV, the King of Spain.

The coins were transferred from Gibraltar to Florida, where Odyssey has its headquarters. However, the Spanish government initiated a lawsuit against the company. In 2011, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta, Georgia, upheld the decision of a Florida judge, who ruled in favor of Spain. The coins were returned in 2012 under a legal decision that no longer allowed any type of appeal or reversal. However, investigators still discovered that the company had wrongfully hidden some objects recovered from the site in Gibraltar.

In the end, the company was forced to return everything and pay a large part of the court costs.

ARCHAEOLOGY PROVIDES CONTEXT

Archaeological treasure hunters pose a problem not only for underwater archaeological heritage but also for heritage pieces and sites located on land. This is not so much because of the material value of the looted antiquities—in fact, contrary to popular belief, archaeologists are not interested in the objects found—but more so in their relationship with other objects and structures.

At an archaeological site, structures and objects are found in levels that take on the form of layers, and what matters is the relationship between objects and structures at any given level.

For example, the fact that Roman coins appear at a site in Northern Europe may suggest that trade with the Roman Empire reached that region.

Because of this, the context in which archaeological remains appear is absolutely key. The archaeologist needs to know exactly where an artifact has been found, at what archaeological level, and what artifacts and structures are on the same level. That is when the finding is useful from a scientific point of view.

THE PRICE OF UNDERWATER CONSERVATION

The main difference between an archaeological site on land and the site of a sunken ship is that, while a land site may contain material remains from various eras, a shipwreck is like a photograph of a moment in time. The materials that we find are exclusively from the moment when the ship sank, indicating styles, fashions, types of food, weapons, and so on.

The other big difference is that studying an underwater site is prohibitively expensive.

To begin with, highly specialized labor is needed, along with diving licenses, underwater equipment, one or more boats, and very expensive excavation equipment that can vacuum up mud or sand from the seabed. In land archaeology, shifts of eight hours or more in length are normal—something unthinkable in underwater archaeology.

The worst is in the conservation of artifacts extracted from the seabed. If there is not a restorer prepared to act on the surface, these objects can very easily degrade in a matter of hours. This type of conservation is extremely expensive.

As an example, one of the best-preserved wrecks in the world at a museum on land is that of the famous warship the Vasa. It is a Swedish ship that foundered and sank in 1628 on its maiden voyage. This ship is one of the main attractions of the city of Stockholm. Nevertheless, the museum makes losses every year due to the cost of preserving the piece.

Odyssey is a company and, as such, it has to make a profit. And making a profit by doing a good job of underwater archaeology is impossible because of the high costs associated with it. Hence, many of these companies do what Odyssey did with the frigate La Mercedes: In this case, the company looted the silver that the ship contained—approximately 600,000 silver and gold coins—and completely ignored any other nonvaluable object from the wreck.

If Odyssey had carried out proper archaeological work, even if the Spanish state had allowed Odyssey to sell the coins, they would have incurred financial losses.

WHO DOES THAT SUNKEN SHIP BELONG TO?

Who is the owner of submerged archaeological heritage sites? This is a difficult question to answer, and, in short, it depends. In theory, everything that falls into the jurisdictional waters of a given country or the nearby continental shelf belongs to that country, unless there is an international treaty involved.

This was the case of La Mercedes; it could be recovered by Spain because there was a treaty with the United States to respect ships’ maritime flags. In other words, if a U.S. ship had sunk more than 100 years ago in Spanish territorial waters, the remains would still belong to the United States—and vice versa.

Since 2001, we have had an international standard for respect toward submerged heritage, which is the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, signed by 20 countries, with more and more are being added. Hopefully, in the future it will be global in scope.