Spirit-Monsters and the Curse of the Chicago Cubs

Superstition is a funny thing. As an anthropologist, I’m not terribly superstitious. I try to be a scientist, after all. But science is fallible, and supposedly rational behavior or objective analysis often isn’t, in retrospect. And every now and then life throws you a curveball—something happens that just leaves you bewildered—and your mind begins wandering outside the confines of reason. You find yourself speculating about origins, cause and effect, results, and unintended consequences.

Oh no, you might think, if I step on that crack, will I break my mother’s back? Or: Jeez, I’ve been having bad luck lately! I wonder if it has anything to do with that ladder I walked under last week.

All human cultures have, enjoy, and abide by superstitions, and one of my all-time favorites comes from Indigenous people who were living in the southern half of Greenland at the time of European contact. They believed that a malevolent, transformational spirit-monster could seek out and destroy one’s enemies. Its name? Tupilaq.

Tupilaq is made manifest as a small figurine assembled out of pieces of animal bone, fur, hair, sinew, and the like. Tupilaq gets its power when a shaman casts a spell over one of these figurines and throws it into the sea. Of its own volition, Tupilaq then seeks out and brings harm to the person or spirit it’s been directed to confront. Which brings me to my point.

I am a lifelong fan of the Chicago Cubs.

The Cubs are enjoying one of the best years in their history and are favored to win the World Series (which begins in late October) for the first time in 108 years. Having been disappointed by the Cubs many times in the last five decades, I’m pessimistic. Even scientists wonder: Why have the Cubs lost so often? Science and history document reality but in this case fail to explain. So let’s look to superstition for an explanation.

The Cubs were one of the winningest teams in baseball during the first half of the 20th century. In 1945, they made it to the World Series. On October 6, local Chicago tavern owner and avid Cubs fan William “Billy Goat” Sianis tried to take his pet goat to Game 4, ostensibly to bring the team good luck. His intentions were noble if unorthodox; he even purchased a ticket so the goat could have a seat. When ushers refused to admit the goat, Sianis shouted “The Cubs ain’t gonna win no more!” and stormed away from Wrigley Field. The Cubs lost the game. They lost the World Series. And they haven’t been to, much less won, the World Series since. The Curse of the Billy Goat was born.

(Today, as the bandwagon grows, millennials who don’t know any better carry placards confidently stating, “I ain’t afraid of no goat!” Now, I can at times appreciate youthful braggadocio, but this is just plain dumb. Fear the goat, my friends. Fear the goat.)

Two dozen years later, in the summer of ‘69, the Cubs enjoyed one of their few successful seasons since 1945. On August 16, the team was comfortably in first place, nine games ahead of the second-place New York Mets. They then went into a nosedive, suffering an 8–17 record in September just as the hated Mets embarked on a brilliant winning streak. The “Miracle Mets” went on to win the World Series.

What was behind the Cubs’ epic collapse?

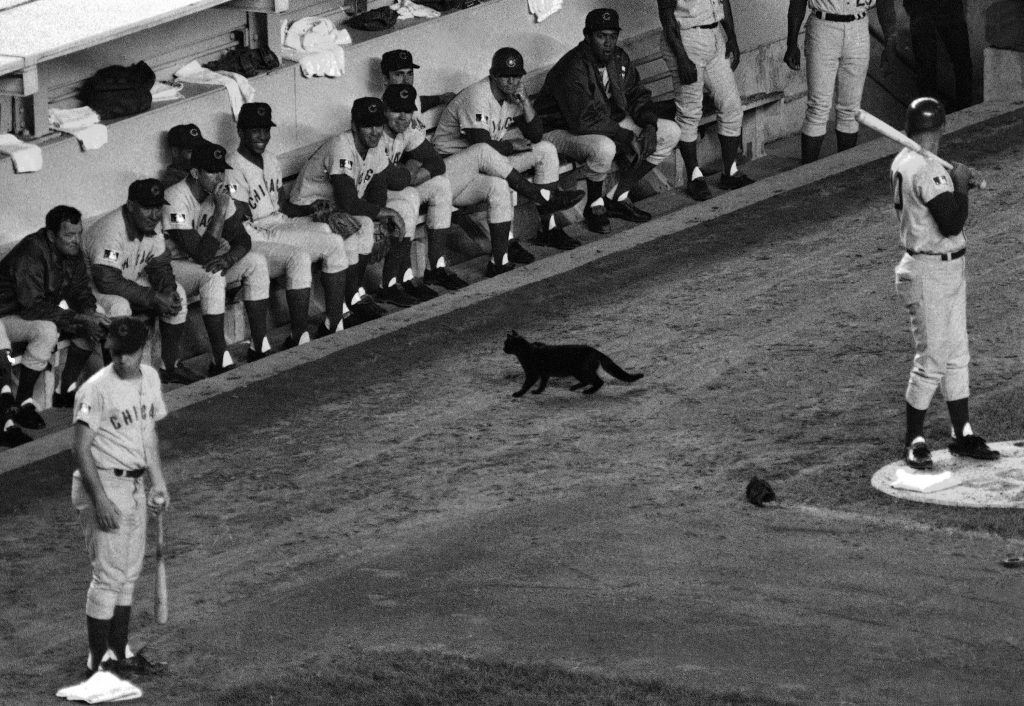

Theories abound. Scientists, pundits, and fans alike point to the toll of day games at Wrigley Field, poor leadership and management, overworked pitchers, disintegrating clubhouse chemistry, and other factors. But real Cubs fans know the cause: On September 9, in a game against the Mets at Shea Stadium in New York, a black cat ran onto the field. (A black cat? On a professional baseball field? Really?) In a berserk panic, the cat ran between the Cubs’ dugout and their star third baseman Ron Santo, who was in the on-deck circle. The Cubs lost the game. Their slump continued. Cause and effect? Undeniably.

Here we are in 2016. The Cubs have clinched the National League Central Division championship and will have home-field advantage throughout the playoffs. They can coast through the rest of the regular season, resting star players and managing their roster to prepare for the ultimate pressure cooker in all of sport (dare I say it?): The Chicago Cubs in the World Series for the first time in 61 years, with a chance to win for the first time in 108 years.

Scientifically, I know I can’t do anything to help the team. Superstitiously, I feel compelled to do whatever I can to help the team. Which brings me back to Tupilaq.

Very few ancient Tupilaq figure carvings are known, because they were made in private, in small numbers, out of perishable materials, and were thrown into the sea in order to go about their business. That doesn’t lead to good preservation.

Christian missionaries working in Greenland in the late 1800s wanted to know what Tupilaq looked like. Indigenous artists responded by carving Tupilaq figures out of walrus and narwhal tusk, whale teeth, animal bone, antler, wood, and other durable materials. Like commercial Hopi kachina dolls in the American Southwest, these Tupilaq figure carvings are not considered sacred, ceremonial, or powerful. Rather, they are educational.

With the arrival of military installations in Greenland during World War II, commercial demand for Tupilaq figure carvings surged, and a full-blown cottage industry developed. Tupilaq carvings are now a major tourist commodity in many North Atlantic countries, especially Greenland and Denmark. They can be found in art galleries and museums all over the world.

What does Tupilaq have to do with the Cubs? Well, considering the circumstances … everything.

In Greenland back in the day, only shamans—those who control supernatural power—could harness Tupilaq. Now I’m no shaman, but desperate times call for desperate measures.

So if you happen to be in Chicago over the next five weeks, don’t be surprised if you find a Tupilaq figure carving washed up on the beautiful shores of Lake Michigan. I made it. I asked it to seek revenge on Billy goats and black cats, as well as Dodgers, Nationals, Red Sox, Rangers, and every other team that makes the playoffs this year. I threw it into Lake Michigan to conduct its business. If you see it, please, for the love of God, leave it alone. It has very important work to do.