Sutton Hoo’s Story Goes Deeper Than The Dig

I first saw the Sutton Hoo burial mounds in 1982. They lay in an English field overlooking the River Deben, overgrown with bracken and overrun with rabbits. As an archaeologist, I knew a little bit about them—enough to feel a burn of excitement plus a twinge of sadness at the state they were in. The next day I put in my application to be the director of a new excavation campaign there: I resolved to solve the mystery of the mounds and make the site into a monument we could be proud of.

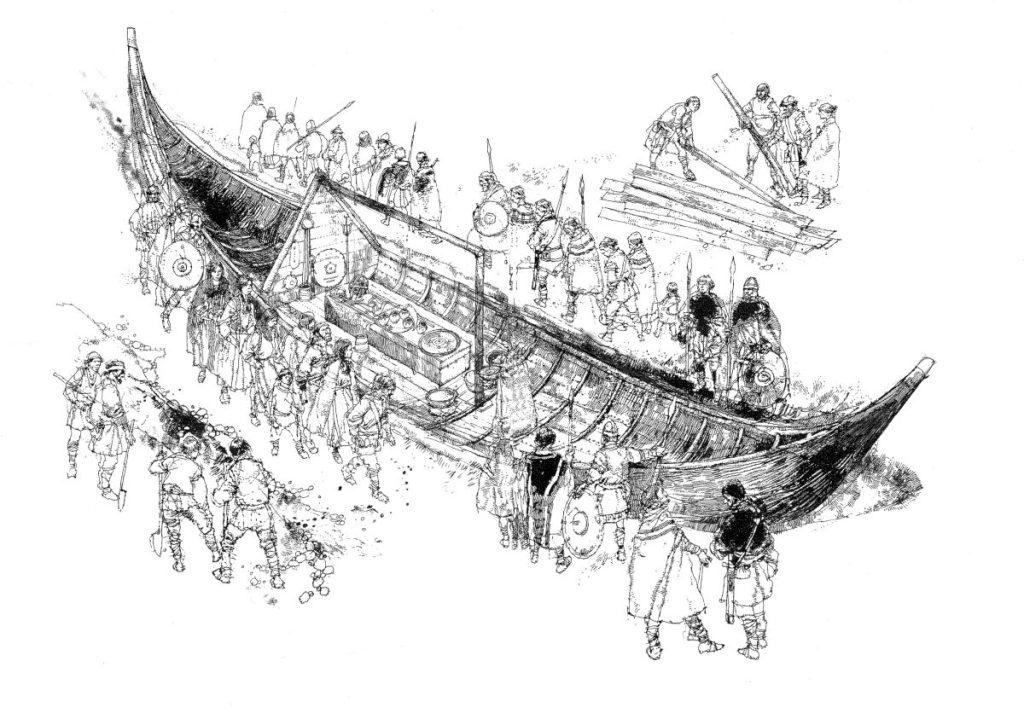

The place had sprung to fame 43 years earlier, just before I was born, through the surprising discovery of a buried ship under the biggest mound. It was the size of a large yacht (27 meters long). Along with it, archaeologists found a resplendent treasure, with an artistry and wealth unparalleled in England. There were objects of gold, garnet, silver, and bronze, exquisitely worked with animal patterns, together with fragments of many kinds of textiles, an otter fur cap, and a flowering plant. At one end of the ship were spears and a shield; at the other lay cauldrons for cooking, silver bowls, drinking horns, and wooden bottles for feasting; and in the center rested the sword and harness, purse, and helmet of a dead man, along with a pile of his clothes. He had been a warrior and a leader, a prominent person in a wealthy community of still-pagan North Sea nations.

This was the discovery celebrated in the recently released film The Dig. The movie tells the story of the excavation, promoted through the initiative of the landowner Edith Pretty (played in the film by Carey Mulligan) and first dug by local excavator Basil Brown (played by Ralph Fiennes). Thanks to some superlative performances, the film offers an irresistible portrait of English society (and its cherished customs) on the brink of World War II.

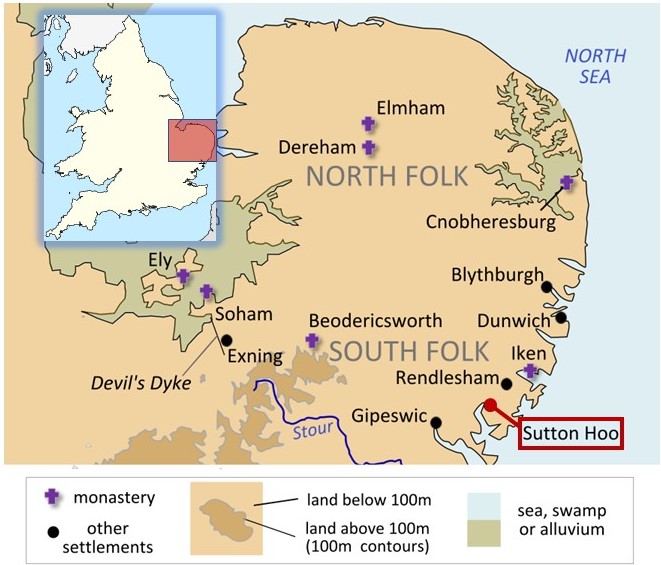

The burial was quickly assigned to a king and, given its location in Suffolk County, to a king of East Anglia. By virtue of the art style, it was placed in the seventh century. The buried man was in all likelihood Raedwald, an Anglo-Saxon who dallied with Christianity and died around A.D. 625. For many, this has remained a sufficient explanation for the Mound 1 treasures, now housed in the British Museum and attracting a wide following.

However, just as the character of British society has radically changed since 1939, so has the meaning of Sutton Hoo, thanks to a further 75 years of intensive research.

This research—begun after the war and led by the British Museum, now owner of the finds—was naturally focused on the objects excavated in 1939, piecing the fragments together and showing the wide range of contacts of the East Angles: from North Britain to Sweden to France and the Mediterranean. The symbolism in the artifacts showed unmistakably that these people belonged to an extensive pagan community of North Sea and Baltic countries, but there was also some exotic silverware bearing Christian insignia from the Mediterranean. A re-excavation of Mound 1 in the 1960s checked for anything that was missed, and the director, Rupert Bruce-Mitford, gathered all the results into a magnificently detailed three-volume account of the ship’s contents.

By the early 1980s, as this book reached the public, the people who studied early medieval Europe were pressing for new excavations at Sutton Hoo. Some were hoping for more treasures, a sight of other kings, or a new flagship project to preen the nation’s identity. But the mood of the archaeological community had changed: These old ideas were no longer the principal drivers.

The new questions were different: What was the ship doing in that spot—why that, why there, why then? What did it signify? It was said to “rewrite history” by shining new light on this particular time and place. Very well. What then was to be the new narrative?

These were my thoughts as I received the news that I had won the chance to direct the new campaign, sponsored by the British Museum, the BBC, the Society of Antiquaries of London, and the Suffolk County Council. The results of our 1983–1992 campaign were published in 2005.

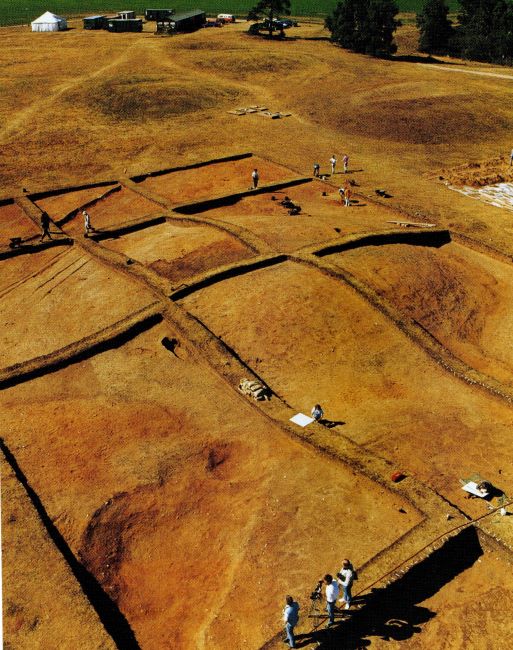

We began with a survey of the whole site to get an inkling of what remained. We found it contained 18 mounds in total. We chose a crossed-shaped area that contained seven mounds in order to examine how the burial rites had developed through time. All but one had been excavated or damaged before (as we had expected), so we developed many new techniques to squeeze the maximum information from what remained.

The upshot was that Sutton Hoo could enjoy a new reality. Our investigation showed that there were actually three cemeteries here: a family burial ground of the sixth century, the elite barrows of the early seventh century (including the ship), and two groups of executions from the eighth through the 11th centuries, featuring the remains of hanged bodies and the postholes of a gallows.

There were links between the first two cemeteries: For example, cremations in bronze bowls seen in the first family burial ground were also a theme of mounds 3, 4, 5, and 18, the early burials of the elite cemetery. Mound 17 came next: A man about 25 years old had been laid in a tree-trunk coffin that had curved clasps. He was buried with a sword, shield, spears, a small bronze cooking pot, a picnic of lamb chops—and the ornamental bridle of his horse, which lay in a pit adjacent. He was equipped for his last adventure.

These were followed by two ship burials: one with a ship over the burial chamber in Mound 2 (excavated three times before) and the famous Mound 1. The most recent burial was that of a woman in Mound 14 who wore silver ornaments and was probably lying on a couch. The execution burials were laid in one group around Mound 5 and in another on the edge of a thoroughfare running along the ridge beside the mounds. There was no doubt that the victims were intended to be seen by those passing by.

These new findings prompted a new view of Mound 1 and its surrounding burials. They could now be seen as a kind of theater in which an Anglian people celebrated the kingdom they were creating through a succession of grand burials that expressed the political aspirations of the day.

In the fifth century, immigrants had made their way up the River Deben from North Germany to settle in Suffolk. One hundred years later, the area had become very wealthy—as shown by recent finds at Rendlesham, an Anglo-Saxon palace site farther upriver. The family that had buried its dead on the banks of the river (our first cemetery) had aspired to leadership roles in the late sixth century. In an eventful episode lasting only 50 years, they went on to create the second cemetery—an elite cluster of barrows celebrating their climb to international prominence.

The well-preserved Mound 1 and Mound 17 showed that objects had been specially selected to make a statement about the dead: a poem of remembrance constructed in objects. This is how a nonliterate people wrote their histories.

We learned that in the Mound 1 burial, the dead man was originally in a large tree-trunk coffin, with a sword and helmet on top and clothes inside it at his feet. It was a piece of theater, leading me to suppose that it was Raedwald’s politically astute wife who had designed it. The message seemed to be: “Times are changing, and we must stand by our people without provoking the Christian alliance that is coming our way.”

As we learn from history books, in the late seventh century, East Anglia acquired a series of Christian kings. The executions were mainly those of young men, who presumably failed to conform with the new regime and paid the price: They were denied burial in the churchyard. Instead, they were buried in the company of the once-brilliant leaders of earlier days, who had no written records but who left an indelible mark on the English landscape.

Thanks to its previous owner, the site of Sutton Hoo is now in the care of the National Trust “for everyone, for ever.” The trust has built a splendid onsite museum with heritage lottery funds. Opened in 2002 by Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney (an enthusiast for Sutton Hoo), the visitor center attracted a million visitors in its first 10 years. And work goes on—on the Sutton Hoo site, in the region, and across the river, where we are now building a full-sized reconstruction of the Mound 1 ship. Each year brings new discoveries of the people who settled in Britain in the fifth century who built Sutton Hoo and became the English.