Stop Projecting Nationalism Onto Stonehenge

In late May, eight images of the United Kingdom’s Queen Elizabeth II were projected onto the megaliths of Stonehenge to celebrate the monarch’s 70 years on the throne. “We’ve brought two British icons together to mark the #PlatinumJubilee,” tweeted English Heritage, the charity that manages the 5,000-year-old monument. The Crown—in a sense the queen herself—owns the site.

The event elicited reactions ranging from delight to unease to outrage. As archaeologists interested in the way contemporary society manipulates the past, we keep an eye open for all sorts of Stonehenge-related nonsense and consider ourselves quite unshockable. But English Heritage’s decision surprised even us in its blindness to nationalist appropriation of the past, as well as its all-round tackiness. (Gordon’s son said it reminded him of a display of cheap souvenir lighters, which seems a fair comment.)

However, this projection was unsurprising for a stone circle onto which so many nationalist fantasies have been projected.

We have written a few times about the ways people have co-opted history and archaeology to create a myth that a “British identity” existed in the ancient past, when there was no such place as “Britain,” let alone a national monarchy. Our piece that generated the most controversy critiqued those who claim Stonehenge and its surrounding landscape helped birth a shared British identity 5,000 years ago, under “national” leaders, at a time when the island had a “unified culture” and was isolated from continental Europe.

This idea of a “Neolithic Brexit” has been used—although not by the archaeologists who unwisely coined the term—to support the separation of Britain from the European Union and to uphold anti-immigration and racist beliefs. But of course, Stonehenge has nothing to do with 21st-century British identity politics and cannot shed light on debates about post-Brexit Britain, immigration, what it is to be British, or the origins of Britishness (whatever that means).

The nationalist appropriation of ancient sites such as Stonehenge is deeply problematic. It can encourage distorted interpretations of research, spark sensationalized media spin, and reinforce harmful prejudices.

BARBECUES AND BRITISHNESS: THE HISTORY OF POLITICIZING STONEHENGE

There is a long history of promoting Stonehenge as the origin of a “British” identity. In the 12th century, Geoffrey of Monmouth, who popularized the tales of King Arthur, claimed the stone circle was built by the wizard Merlin and described it as the “omphalos [navel] of Britain.” This mystical idea was revived in all seriousness in a 2012 book that describes Stonehenge as “integrating the cosmological aspects of earth, sun, and moon into a single entity which also united the ancestors of the people of Britain.”

The book and a related press release promoted the ideas that Stonehenge was “constructed during a period of cultural isolation from the continent” and was built to “unify the peoples of Britain, after a long period of conflict and regional difference.” News outlets enthusiastically picked up the story.

Meanwhile, archaeological studies of animal remains found at the Stonehenge landscape initially presented conservative interpretations of feasting events in the area. But over the years, further research and publications reinterpreted and augmented the claims. Eventually, media outlets were reporting that people brought animals to Stonehenge from all parts of Britain (including northern Scotland) for culturally unifying “epic barbecues.”

In 2019, researchers published isotope analysis of pig teeth found around Stonehenge, presumably left over from feasts. This research and the accompanying press releases prompted a headline in The Daily Telegraph that read, “‘Neolithic Brexit’ Unearthed at Stonehenge Shows British Identity Began 5,000 Years Ago, Archaeologists Say.”

We have argued that this interpretation merely follows decades-old, lazy preconceptions about the supposed preeminent role of Stonehenge in the Neolithic period of Britain. In addition, the mythos of an ancient pan-British identity fails to take into account the variability of life in late Neolithic Britain, evident in the diverse regional styles of monuments, buildings, funerary practices, and aspects of the economy.

Worse still, this interpretation was presented with no obvious consideration of Stonehenge’s place as a powerful symbol of English identity, or how this narrative might be consumed by right-leaning media and readers.

BREXIT AND BIGOTRY: THE DANGERS OF POLITICIZING STONEHENGE

Neolithic monuments are frequently used to invoke British exceptionalism. The far-right British National Party has argued in their manifesto that great megalithic monuments were achievements of the first indigenous (White) Britons. Neofascist groups have been using Neolithic sites in the south of England for ethnonationalist ceremonies. The reader comments on The Daily Telegraph’s Stonehenge article centered on political identity, race, immigration, pro- and anti-Brexit point-scoring, and arguments about Britishness, such as “the way things are going, British identity will die in the next 50 years.”

But while Stonehenge is framed as a nationalist symbol of “Britishness,” in reality it isn’t a British icon at all; it is solely an icon of a specifically English identity. (There is a long, problematic tradition in Britain of confusing what is “British”—which encompasses England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland—and what is “English.”) As such, it was perhaps inevitable that this monument would be used in support of Brexit, which has been described as an English nationalist political project in which Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland were “afterthoughts.” This confirms Kenny’s Brexit hypothesis, “the proposition that any archaeological discovery in Europe can—and probably will—be exploited to argue in support of, or against, Brexit.”

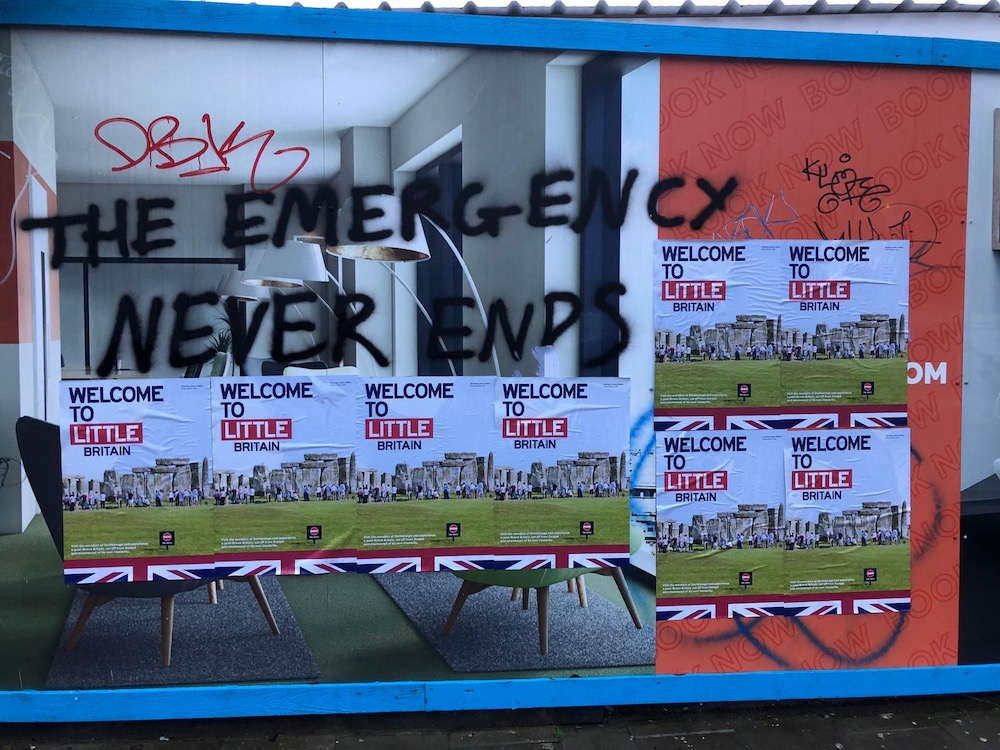

Stonehenge has also been co-opted into arguments about immigration, often mobilized by nativist racists who want the monument to have been built by White Britons like themselves. Artists have satirized this trend. Jeremy Deller created a mock road sign that read “Stonehenge: Built by immigrants,” emphasizing that the people who constructed the stone circle were migrants descended from populations originating in modern-day Turkey. Artist Simon Roberts created posters titled Welcome to Little Britain, featuring Stonehenge and a Union flag. The posters state, “Visit the wonders of Stonehenge and experience a post-Brexit Britain, cut off from Europe and enamoured of its own insularity.”

English Heritage has compounded these issues with its recent royal projection, aligning itself with a particular view of Stonehenge as a monument reflecting the English nationalist character of the current government.

Equally concerning is the unwitting legitimization of these ideas by archaeological and ancient DNA genetics research promoted through clickbait press and social media interactions. When archaeologists, their institutions, and their funding bodies support—or fail to challenge—suggestions that the monuments of the Stonehenge area embody “Britishness,” “British traits,” and “British unity,” they are adding fuel to the nationalist fire.

Stonehenge has always been a political monument, belonging to and used in support of the establishment, from those who organized its construction in the Neolithic period to archaeologists and politicians today. Yet this stone circle has also always been used to subvert and satirize power structures.

In that sense, it was created and continues to exist so beliefs and convictions can be projected onto it by those who seek legitimacy for good and ill. Archaeologists and the general public should recognize this reality and take a more thoughtful approach to how they discuss, depict, interpret, and promote Stonehenge and other ancient sites.