What a Shipwreck’s Tree Rings Reveal

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished under Creative Commons.

The wrecking of the Dutch East India Company ship Batavia in 1629 is perhaps the best-known maritime disaster in Australian history. The subject of books, articles, plays, and even an opera, Batavia was wrecked on a chain of small islands off the coast of Western Australia.

Of Batavia’s 341 crew and passengers, 40 drowned trying to get off the ship, while all others made it to the uninhabited islands nearby. The captain, senior officers, two women, and one child left in one of the ship’s boats to get help. But further tragedy followed.

A group of men on the islands who had gathered around the acting commander deliberately drowned, strangled, cut the throats, or brutally hacked to death 125 children, women, and men. When the rescue party returned months later, they managed to overpower this death squad and bring the remaining survivors to safety. Together with its many victims and the murderers, Batavia’s wreckage was left in the Houtman Abrolhos archipelago.

The Dutch ship was 45.3 meters long and 600 metric tons in size. It sank on its maiden voyage to Southeast Asia. The shipwreck was found in the 1960s off Morning Reef and was excavated in the 1970s.

The surviving stern section, now in Fremantle’s Western Australian Shipwrecks Museum, is the only portion of any early 17th-century Dutch East India ship raised from the seabed and preserved.

Previously, historians could only guess where the timber for such ships came from, when it was felled, or how it was used, as archival records of Dutch timber trade before 1650 are rare or lost.

But in new research, we studied the tree rings of the Batavia shipwreck timbers. We have found that the oak for the hull was sourced from two separate forests (in northern Germany and the Baltic region), with wood for the framing elements coming predominantly from the forests of Lower Saxony. The timber was processed shortly after the trees were felled (in 1625 or later) and was still green when the shipbuilders cut and bent the planks into shape.

Knowing more about these timbers helps us understand the Dutch success in world trade, including how they managed to build such large ocean-going vessels and so many of them.

A UNIQUE ARCHAEOLOGICAL DATASET

Batavia’s remains provide a rare archaeological resource for tree-ring examination because exact dates of its construction and sinking are known.

Construction began sometime in the spring of 1626, and the ship set sail from Texel (the Netherlands) to the East Indies (known today as Indonesia) in October 1628. It struck a reef on June 4, 1629. As Batavia had never undergone repairs or maintenance work, we know every piece of timber belongs to the original structure.

When Batavia was built, the Dutch were the foremost shipbuilders in Europe. By 1640, for example, around 1,000 seagoing ships were being constructed in the Netherlands each year, mostly for export markets.

The Dutch lacked domestic timber resources to supply the bustling shipbuilding industry and yet would have needed hundreds, perhaps thousands, of oak trees to build Batavia.

Where did all this timber come from? The Dutch East India Company archives provide no detailed information on where its shipyards bought timber at the time of Batavia’s construction. While the company kept detailed records from the mid-17th century onward, hardly any of those from the early 1600s have survived.

Fortunately, tree rings can provide answers to those questions. Trees in temperate climate zones form a growth ring each year, just under the bark. This sequence of growth rings produced over years and decades acts like an environmental bar code, a growth pattern that is particular to the place where they grew and died.

This growth pattern is very similar for trees of the same species growing in the same area.

By measuring the ring widths from many trees, a reference tree-ring chronology can be built. Then, we can cross match the growth pattern of a specific timber to such reference chronologies, establishing when the tree was felled and where it had grown. This field of study is known as dendrochronology.

The many Batavia timbers we sampled had only heartwood, or interior rings, demonstrating that Dutch shipbuilders discarded the sapwood (outer rings). Sapwood is softer and contains substances that make it more vulnerable to insect infestation and decay.

Furthermore, the outermost heartwood ring of the Batavia hull planks that we sampled dates to 1616. When accounting for the missing sapwood (nine rings for Baltic oak), this means the trees were felled in 1625 or later.

The timber was processed shortly after the trees were felled. All this demonstrates that Batavia’s builders were skilled craftspersons, intimately familiar with the properties of the wood they used.

EFFICIENT SHIPBUILDING AND REGIONAL SELECTION

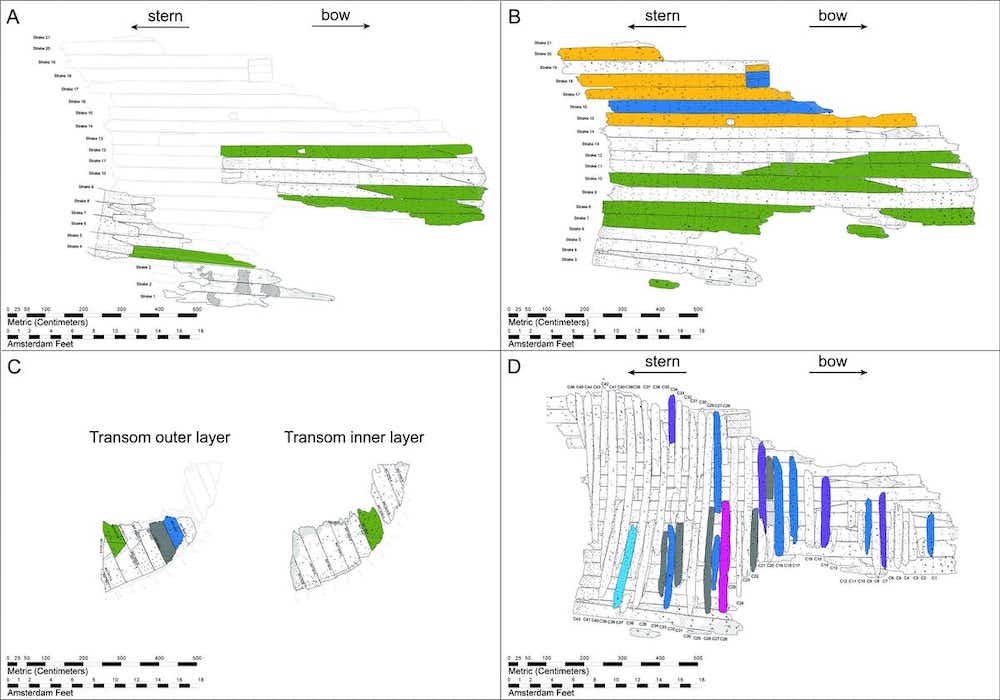

The oak timber used in Batavia’s hull planks came from two forests. Trees from near Lübeck in northern Germany were used above the ship’s waterline, while timber from the Baltic region of Northeastern Europe was applied exclusively below the waterline.

This Baltic timber was prized by artists like Rembrandt, who used it for panels on which to paint. Trees from this region had beautifully straight trunks with very fine growth rings, making the wood easy to work and stable.

Obviously, company shipbuilders valued these same properties when building ships strong enough to endure several return voyages to Southeast Asia. They avoided using trees with knots in the hull and preferred wood from which they could fashion long and strong planks.

In contrast, we found that the timber for Batavia’s framing elements came predominantly from the forests of Lower Saxony (northwest Germany). Frames utilized the strong properties of these oaks’ curved wood fibers. As it was sourced closer to home, this timber may have been cheaper and easier to acquire.

Our study was only possible because Batavia’s hull was raised in its entirety. Waterlogged wood is mushy, so extracting samples from the timbers while still under water is always challenging. It also would have required cutting out large sections of the ship to access all the different elements.